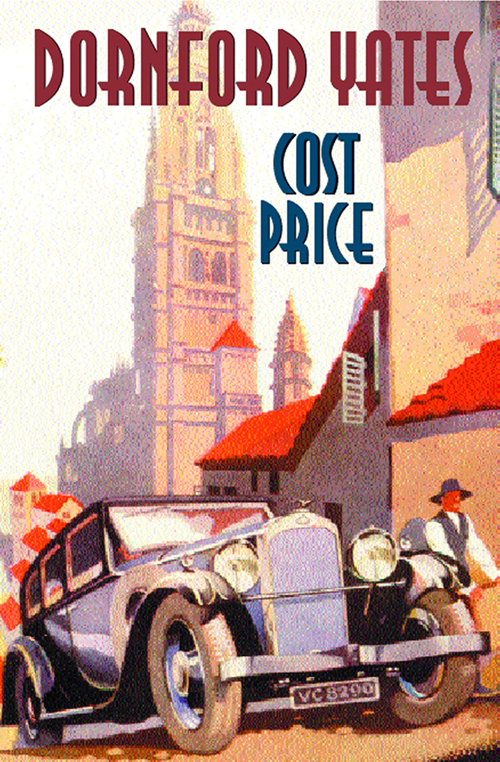

Cost Price

Cost Price

First published in 1949

© Estate of Dornford Yates; House of Stratus 1949-2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The right of Dornford Yates to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

This edition published in 2011 by House of Stratus, an imprint of

Stratus Books Ltd., Lisandra House, Fore Street, Looe,

Cornwall, PL13 1AD, UK.

Typeset by House of Stratus.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library and the Library of Congress.

| | EAN | | ISBN | | Edition | |

| | 1842329707 | | 9781842329702 | | Print | |

| | 0755126904 | | 9780755126903 | | Kindle | |

| | 0755127110 | | 9780755127115 | | Epub | |

This is a fictional work and all characters are drawn from the author’s imagination.

Any resemblance or similarities to persons either living or dead are entirely coincidental.

Born ‘Cecil William Mercer’ into a middle class Victorian family with many Victorian skeletons in the closet, including the conviction for embezzlement from a law firm and subsequent suicide of his great-uncle, Yates’ parents somehow scraped together enough money to send him to Harrow.

The son of a solicitor, he at first could not seek a call to the Bar as he gained only a third class degree at Oxford. However, after a spell in a Solicitor’s office he managed to qualify and then practised as a Barrister, including an involvement in the Dr. Crippen Case, but whilst still finding time to contribute stories to the

Windsor Magazine

.

After the First World War, Yates gave up legal work in favour of writing, which had become his great passion, and completed some thirty books. These ranged from light-hearted farce to adventure thrillers. For the former, he created the

‘Berry’

books which established Yates’ reputation as a writer of witty, upper-crust romances. For the latter, he created the character

Richard Chandos

, who recounts the adventures of

Jonah Mansel

, a classic gentleman sleuth. As a consequence of his education and experience, Yates’ books feature the genteel life, a nostalgic glimpse at Edwardian decadence and a number of swindling solicitors.

In his hey day, and as testament to his fine writing, Dornford Yates’ work often featured in the bestseller list. Indeed,

‘Berry’

is one of the great comic creations of twentieth century fiction; the

‘Chandos’

titles also being successfully adapted for television. Along with Sapper and John Buchan, Yates dominated the adventure book market of the inter war years.

Finding the English climate utterly unbearable, Yates chose to live in the French Pyrenées for eighteen years, before moving on to Rhodesia (as was), where he died in 1960.

‘Mr Yates can be recommended to anyone who thinks the British take themselves too seriously.’ - Punch

‘We appreciate fine writing when we come across it, and a wit that is ageless united to a courtesy that is extinct’ - Cyril Connolly

In telling this tale, I have found it impossible not to refer to incidents related in two other of my books. It is neither necessary nor desirable for any reader of this book to read those but, in case someone should wish to confirm the reports of either Punter or Richard Chandos, let me say that

‘SAFE CUSTODY’

will bear out the one and

‘BLIND CORNER’

the other.

DORNFORD YATES.

“Where’s yer case?” said the valet, cigarette box in hand.

“On the bed,” said his master. “Use your eyes.”

“Sez you,” said the valet. He began to replenish the case. “Too strong fer me, these fags.”

“I’m glad of that,” said the other. “Give me my coat.”

The jacket was entered and adjusted. Edward Osric Friar was a well-dressed man.

“Dinin’ at the Club?” said the valet.

“Your supposition,” said his master, “is correct.”

“Along with bishops an’ judges. Enough to make a cat laugh, it is.”

“It takes all sorts,” said his master, “to make a world.”

“I’ll say it does,” said Sloper – to give him his name. “’Ere’s you, a firs’-class crook, ’ob-nobbin’ with judges an’ bishops–”

“That is why,” said his master, “I am a first-class crook. I am above suspicion – a most important thing. By the way, I shall want you tonight; so be in by ten.”

The other sighed.

“An’ I meant to go to the flicks. They’re showin’–”

“Business first,” said Friar. “I meant to go to the play. Ever heard of a crook called Punter?”

“Punter,” said the valet, pinching the end of his nose. “A fair-’aired bloke, ’igh-coloured and ’alf a dude?”

“That would be him.”

“’E’s knocked about,” said Sloper. “’E used to work with ‘Rose’ Noble. ’E’s done one stretch, I know, but I can’t remember why. Auntie Emma’s used him. People like ’im, I think: but ’e’s nothin’ wonderful.”

“He’s a lazy swine,” said Friar, “but he’s coming to see me tonight.”

“Is he, though,” said Sloper. “An’ wot does he know?”

“That,” said his master, “is what I propose to find out. Give me my overcoat.”

Six minutes later, he entered a famous Club, which stands in Pall Mall.

Friar was a fine looking man of forty-five. He was a Doctor of Law, a Fellow of Oxford, and a distinguished Reader of one of the Inns of Court. As such, his duties were slight: so was his remuneration. Yet he lodged in Mayfair, living in very good style. He was a recognized authority upon old silver and a familiar figure at Christie’s Great Rooms. He seldom made a purchase, but he was a connoisseur. Physically very strong, he took the greatest care to keep himself fit. He was completely ruthless, as Sloper could tell: but he never ‘worked’ in England – the risk was too great.

This evening he found himself next to Professor Lebrun: they had a long talk on archaeology: he drank his coffee and brandy with a leading anaesthetist; and soon after ten o’clock he left the Club to walk to his excellent flat.

As he was approaching the block, he observed a figure moving on the opposite side of the street. Experience, rather than instinct, told him that this was his man. The malefactor believes in reconnaissance.

Friar crossed the street.

“Good evening, Punter,” he said.

“Er, good evening, sir.”

“Before your time, I see. With me that’s a very good fault. Come along in.”

By no means easy, Punter followed his host. He had meant to ‘have a look round’, but he had left it too late. He was not at all sure of his host, who had a compelling air.

Friar led the way upstairs and into an elegant room. Then he indicated a chair.

“Sit down there,” he said, “and take a cigar.”

Punter obeyed.

Friar put off his hat and coat and took his seat on a table, swinging a leg.

“Last night I heard you talking. Who was your friend?”

“We call him Lousy. I don’t know his other name.”

“Doesn’t he work with Auntie?”

“That’s right. ’E can play with a car.”

“You were talking about a show you had in Austria. A castle, you mentioned – The Castle of Hohenems.”

“That was a wash-out,” said Punter. “Lucky to save me life, if you ask me.”

“I’d like to hear about it.”

“There ain’t nothin’ doin’ there, sir. We ’anded the stuff away.”

“I’d like to hear about it.”

Punter put a hand to his chin.

“A bloke called Harris,” he said. “He called me in. A treasure of jools, there was, hid up in a vault. Somethin’ very special – there ain’t no doubt about that. All carved, they was, an’ worth a million or more. ’Istorical – that’s the word. Belonged to the Pope, they did: and he’d walled them up.”

“That’s right,” said Friar. “I’ve seen the catalogue.”

“’Ave you, though?” said Punter. “Well, I seen a photograph – o’ the catalogue, I mean. Written down in a prayer book, it was.”

“That’s right,” said Friar. “Interleaved with a breviary. The original is in New York. They were wonderful gems.”

“So Harris said,” said Punter. “An’ I’ll say we — near ’ad them. But somethin’ went wrong.”

“Tell me everything.”

Punter took a deep breath.

Then—

“We near — ’ad them,” he said. “The jools was there in this castle, an’ we was outside: but we knew where they was hid. Ferrers didn’t. ’E knew they was there somewhere, but ’e didn’ know where – or, if he did, he didn’t know ’ow to reach them.”

“Who was Ferrers?” said Friar.

“He lived at Hohenems. Owned the place with his cousin – I can’t remember ’is name. An’ another was workin’ with them – Palin, his name was. ’E was the — that laid me out. But ’e didn’ live there. ’E ’ad rooms at an inn about thirty miles off.”

“Where were they hidden?” said Friar.

“They was walled up,” said Punter. “Right down in one o’ the dungeons – you never see such a place. But that was nothin’. What was beatin’ Ferrers was ’ow to get at the wall.”

“Why couldn’t he get at the wall?”

“’Cause o’ the water,” said Punter. “A — great waterfall, a-bellowin’ over the wall. You never see such a thing. I tell you it give me the creeps.”

“What, inside the dungeon?” said Friar.

“Inside the dungeon,” said Punter. “I give you my word–”

“Why wasn’t it flooded?”

“Fell down into a drain, to take it away.”

“I’m beginning to see. The water made a curtain over the wall?”

“I’ll say it did. Tons an’ tons o’ water a-roarin’ down. An’ if you went too near, you was swep’ down the drain. Talk about a—”

“So you had to cut off the water, to reach the wall.”

“That’s right. And so we did. Built a — great sluice – it took us days. On the ’ill above the castle, to stop the fall. Then one night we lets down the sluice an’, soon as the water stops, we goes up the drain. I won’ forget that in a ’urry – talk about slime. An’, as I remarks to ’Arris, ‘Supposin’ the water comes back.’ Nice sort o’ death we’d’ve ’ad, I don’ think.”

“But you didn’t. You got up all right.”

“An’ wot did we find? You’ll ’ardly believe it, sir, but them — squirts ’ad the wall down. We’d stopped their — water, an’ there they was in the chamber, collectin’ the goods… But they made one mistake, they did. They never thought to watch out.”

“What happened?” said Friar.

“We came in be’ind them, an’ we was armed. ‘Put them up,’ says ’Arris, an’ that was that.”

Friar was frowning.

“I thought you said that you’d handed the stuff away.”

“So we did,” said Punter, miserably. “’Arris sends me to watch out by the dungeon door, while ’e an’ the others was stowing the jools into bags. An’ then somethin’ must ’ave gone wrong. Wot it was, I dunno. There weren’t no noise nor nothin’: but after about an hour, that —, Palin, comes up an’ lays me out. An’ when I come to, me wrists is tied an’ I’m on a stable floor. I never see ’Arris again an’ I never see Bunch. Done in, I take it. Though ’ow it ’appened, Gawd knows. I mean, we ’ad them cold.”

There was a little silence.

Then—

“What happened to you?”

“Chauffeur took me to Salzburg and put me on board a train.”

“Were you the only one left?”

“’Cept for Bugle. ’E got out all right, ’cause ’e’d gone to let down the sluice. Nice fuss ’e made, when we met. Said I’d double-crossed ’im. ‘See ’ere,’ I says. ‘Three months’ – ’ard labour, the — goods in me ’ands, an’ then me block knocked off an’ a third-class carriage to England. Is that wot you call double-crossin’?’”

“Where is he now?”

“Bugle? He’s dead, I think. Working with Pharaoh, he was, along with Dewdrop an’ Rush. They went off on some very big job, but they never come back. There’s the Continen’ for you – if you win, you’ve got it: but if you lose, you’re dead.”

“There’s something in that.”

“I’ll say there is… Well, that’s what happened, sir. So you see there’s nothin’ doin’. We opened the safe for Ferrers, an’ now the jools is gone.”

“No, they’re not,” said Friar. Punter stared. “I’ll lay you any money, those jewels are still where they were.”

“Wot, be’ind the water an’ all?”

“Why not? They’re valuable things: and the chamber in which they were found is better than any safe.”

“But Ferrers wouldn’ o’ kep’ them. Wot’s the good of–”

“Ferrers has kept them,” said Friar. “I don’t know why he has, but I know he has. I’ll tell you how I know, Punter. Because, if such gems had been sold, the whole of the world would know. There were more than a hundred, if I remember aright.”

“’Undred an’ twenty-seven.”

“And every one of those a historical gem. All sculptured jewels, that cannot be broken up. The sale of but half a dozen would set the world by the ears.”

“You don’ say?”

“I do, indeed. And I know what I’m talking about. I move in art circles, myself. That’s how I came to see that catalogue. And I tell you here and now that those gems are still there. And another thing I tell you – that such a collection of gems is beyond all price.”

There was another silence. Punter’s cigar had gone out; but he made no attempt to relight it. The news was too big.

“You goin’ to ’ave a stab at it, sir?”

“More than a stab. I’m going to have them, Punter. D’you want to come in?”

“I’m not buildin’ any more sluices.”

“You won’t be asked to. There must be an easier way.”

“An’ that castle’s a — to enter. Walls about ten foot thick, an’ the goin’ outside enough to break a goat’s ’eart.”

“I expect there’s a door,” said Friar.

“There’s a — drawbridge,” said Punter. “You can’t force them.”

“No other way in?”

“The terrace ain’t bad. A ladder would take you up. But ‘Once bitten, twice shy’, you know, sir. I’ll lay they’re watchin’ out.”

“How long is it since you failed?”

Punter appeared to reflect.

Then—

“Five years,” he said.

“Good enough,” said Friar, and got to his feet. “But we’d better not wait too long, or Ferrers will take them out. Things are going to happen in Austria. If he can’t take anything else, he’ll take those gems.”

“I wish I knew,” said Punter, “wot ’appened to bust the balloon. We ’ad the jools – I saw them, done up in three sort o’ bales. An’ the squirts was done – they daren’t move ’and nor foot, for they ’ad a lady with them and ’Arris was out to kill.”

Friar crossed to a little table, on which was a tray. He poured two whiskeys and sodas. Then he returned to Punter, tumblers in hand.

“Thank you, sir. Here’s your best.”

The two of them drank.

Then—

“D’you want to come in?” said Friar. “If not, I’ll give you a tenner to hold your tongue.”

“And if I do?”

“I take the lion’s share, and you come next. We shan’t be able to spend it; there’ll be so much. Each gem will be an income: I’ll see to that.”

“Of course, I know the castle,” said Punter. “An’ round about.”

“Your knowledge,” said Friar, “would save me a lot of time.”

“I’ll say it would. But I don’t want another wash-out. I mightn’ be lucky this time. If I ’adn’ been watchin’ out… An’ as it was, ’e — near broke my neck. Punch like the kick of a ’orse. My Gawd, I can feel it now.”

“You won’t have another wash-out, unless you let me down.”

“Oh, I wouldn’ do that, sir.”

“Not twice,” said Friar. “But serve me faithfully and you’ll find me generous.”

Punter fingered his chin.

“I wish I knew wot ’appened,” he said. “Somebody chucked a spanner into the works. Must ’ave. It looked like Mansel, you know: but I never saw the —, if he was there.”

“I’ve heard of Mansel,” said Friar. “Is he any good?”

“— wizard,” said Punter, “an’ that’s the truth. ‘Rose’ Noble ’ad ’im cold, but ’e did ’im in. ’E’d lose the race; but, when the numbers went up, you’d find he’d won.”

“I’d like to meet him,” said Friar.

“Well, I don’ want to,” said Punter. “I’ve done it twice, an’ I don’ want to do it again. I see ’im kill ‘Rose’ Noble. Shot ’im between the eyes. An’ then ’e burst Auntie – I wasn’ in on that. His sister’s pearls ’ad been taken, an’ Auntie was hornin’ in. I tell you, Mansel’s a —. An’ Chandos is pretty tough. ’Alf a giant, like Palin, an’ does as Mansel says. Gawd, wot a pair! If I thought they was backin’ Ferrers, you wouldn’ see me for dust.”

“Nobody’s backing Ferrers. He isn’t backing himself, as far as I know. But that’s what we’ve got to find out. This is the tenth of April. I shall be ready to leave by the first of May. I must get the hang of the country, find out Ferrers’ movements and things like that. What I call ‘reconnaissance’, Punter. And if you’re coming with me, I must know two days from now. You’d better think it over.” Friar rose and crossed to the door. “Have a word with my servant, Sloper. He will be working with us and he knows my ways.” He opened the door and called. “Sloper, look after Punter for half an hour.”

“Sez you,” breathed Sloper, backing away from the door.