Collected Prose: Autobiographical Writings, True Stories, Critical Essays, Prefaces, Collaborations With Artists, and Interviews (63 page)

Authors: Paul Auster

The poem is created only in choosing the most difficult path. Every advantage must be suppressed and every ruse discarded in the interests of reaching this limit — an endless series of destructions, in order to come to a point at which the poem can no longer be destroyed. For the poetic word is essentially the creative word, and yet, nevertheless, a word among others, burdened by the weight of habit and layers of dead skin that must be stripped away before it can regain its true function. Violence is demanded, and Dupin is equal to it. But the struggle is pursued for an end beyond violence — that of finding a habitable space. As often as not, he will fail, and even if he does not, success will bear its own disquiet.

The torch which lights the abyss, which seals it up, is itself an abyss.

The strength that Dupin speaks of is not the strength of transcendence, but of immanence and realization. The gods have vanished, and there can be no question of pretending to recover the divine logos. Faced with an unknowable world, poetry can do no more than create what already exists. But that is already saying a great deal. For if things can be recovered from the edge of absence, there is the chance, in so doing, of giving them back to men.

1971

André du Bouchet

…

this irreducible sign — deutungslos — … a word beyond grasping, Cassandra’s word, a word from which no lesson is to be drawn, a word, each time, and every time, spoken to say nothing

…

Hölderlin aujourd’hui (

lecture delivered March 1970 in Stuttgart to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Hölderlin’s birth

)

(

this joy

…

that is born of nothing …

)

Qui n’est pas tourné vers nous (1972)

Born of the deepest silences, and condemned to life without hope of life (

I found myself / free / and without hope

), the poetry of André du Bouchet stands, in the end, as an act of survival. Beginning with nothing, and ending with nothing but the truth of its own struggle, du Bouchet’s work is the record of an obsessive, wholly ruthless attempt to gain access to the self. It is a project filled with uncertainty, silence, and resistance, and there is no contemporary poetry, perhaps, that lends itself more reluctantly to gloss. To read du Bouchet is to undergo a process of dislocation: here, we discover, is not here, and the body, even the physical presence within the poems, is no longer in possession of itself — but moving, as if into the distance, where it seeks to find itself against the inevitability of its own disappearance (…

and the silence that claims us, like a vast field.

) “Here” is the limit we come to. To be in the poem, from this moment on, is to be nowhere.

*

A body in space. And the poem, as self-evident as this body. In space: that is to say, this void, this nowhere between sky and earth, rediscovered with each step that is taken. For wherever we are, the world is not. And wherever we go, we find ourselves moving in advance of ourselves — as if where the world would be. The distance, which allows the world to appear, is also that which separates us from the world, and though the body will endlessly move through this space, as if in the hope of abolishing it, the process begins again with each step taken. We move toward an infinitely receding point, a destination that can never be reached, and in the end, this going, in itself, will become a goal, so that the mere fact of moving onward will be a way of being in the world, even as the world remains beyond us. There is no hope in this, but neither is there despair. For what du Bouchet manages to maintain, almost uncannily, is a nostalgia for a possible future, even as he knows it will never come to pass. And from this dreadful knowledge, there is nevertheless a kind of joy, a joy … that is born of nothing.

*

Du Bouchet’s work, however, will seem difficult to many readers approaching it for the first time. Stripped of metaphor, almost devoid of imagery, and generated by a syntax of abrupt, paratactic brevity, his poems have done away with nearly all the props that students of poetry are taught to look for — the very difficulties that poetry has always seemed to rely on — and this sudden opening of distances, in spite of the lessons buried in such earlier poets as Hölderlin, Leopardi, and Mallarmé, will seem baffling, even frightening. In the world of French poetry, however, du Bouchet has performed an act of linguistic surgery no less important than the one performed by William Carlos Williams in America, and against the rhetorical inflation that is the curse of French writing, his intensely understated poems have all the freshness of natural objects. His work, which was first published in the early fifties, became a model for a whole generation of postwar poets, and there are few young poets in France today who do not show the mark of his influence. What on first or second reading might seem to be an almost fragile sensibility gradually emerges as a vision of the greatest force and purity. For the poems themselves cannot be truly felt until one has penetrated the strength of the silence that lies at their source. It is a silence equal to the strength of any word.

1973

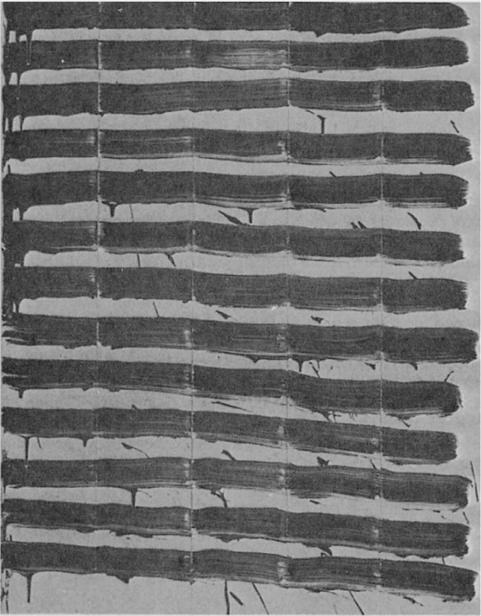

Black on White

Recent paintings by David Reed

The hand of the painter has rarely instructed us in the ways of the hand. When we look at a painting, we see an accumulation of gestures, the layering and shaping of materials, the longing of the inanimate to take on life. But we do not see the hand itself. Like the God of the deists, it seems to have withdrawn from its own creation, or vanished into the density of the world it has made. It does not matter whether the painting is figurative or abstract: we confront the work as an object, and, as such, the surface remains independent of the will behind it.

In David Reed’s new paintings, this has been reversed. Suddenly, the hand has been made visible to us, and in each horizontal stroke applied to the canvas, we are able to see that hand with such precision that it actually seems to be

moving

. Faithful only to itself, to the demands of the movement it brings forth, the hand is no longer a means to an end, but the substance of the object it creates. For each stroke we are given here is unique: there is no backtracking, no modeling, no pause. The hand moves across the surface in a single, unbroken gesture, and once this gesture has been completed, it is inviolate. The finished work is not a representation of this process — it is the process itself, and it asks to be

read

rather than simply observed. Composed of a series of rung-like strokes that descend the length of the canvas, each of these paintings resembles a vast poem without words. Our eyes follow its movement in the same way we follow a poem down a page, and just as the line in a poem is a unit of breath, so the line in the painting is a unit of gesture. The language of these works is the language of the body.

Some people will probably try to see them as examples of minimal art. But that would be a mistake. Minimal art is an art of control, aiming at the rigorous ordering of visual information, while Reed’s paintings are conceived in a way that sabotages the idea of a preordained result. It is this high degree of spontaneity within a consciously limited framework that produces such a harmonious coupling of intellectual and physical energies in his work. No two paintings are or can be exactly alike, even though each painting begins at the same point, with the same fundamental premises. For no matter how regular or controlled the gesture may be, its field of action is unstable, and in the end it is chance that governs the result. Because the white background is still wet when the horizontal strokes are applied, the painting can never be fully calculated in advance, and the image is always at the mercy of gravity. In some sense, then, each painting is born from a conflict between opposing forces. The horizontal stroke tries to impose an order upon the chaos of the background, and is deformed by it as the white paint settles. It would surely be stretching matters to interpret this as a parable of man against nature. And yet, because these paintings evolve in time, and because our reading of them necessarily leads us back through their whole history, we are able to re-enact this conflict whenever we come into their presence. What remains is the drama: and we begin to understand that, fundamentally, these works are the statement of that drama.

In the last sentence of Maurice Blanchot’s novel,

Death Sentence

, the nameless narrator writes: “And even more, let him try to imagine the hand that has written these pages: and if he is able to see it, then perhaps reading will become a serious task for him.” David Reed’s new work is an expression of this same desire in the realm of painting. By allowing us to imagine his hand, by allowing us to

see

his hand, he has exposed us to the serious task of seeing: how we see and what we see, and how what we see in a painting is different from what we see anywhere else. It has taken considerable courage to do this. For it pushes the artist out from the shadows, leaving him with nowhere to stand but in the painting itself. And in order for us to look at one of these works, we have no choice but to go in there with him.

1975

Twentieth-Century French Poetry

I

French and English constitute a single language.

Wallace Stevens

This much is certain: If not for the arrival of William and his armies on English soil in 1066, the English language as we know it would never have come into being. For the next three hundred years French was the language spoken at the English court, and it was not until the end of the Hundred Years’ War that it became clear, once and for all, that France and England were not to become a single country. Even John Gower, one of the first to write in the English vernacular, composed a large portion of his work in French, and Chaucer, the greatest of the early English poets, devoted much of his creative energy to a translation of

Le Roman de la rose

and found his first models in the work of the Frenchman Guillaume de Machaut. It is not simply that French must be considered an “influence” on the development of English language and literature; French is a part of English, an irreducible element of its genetic make up.

Early English literature is replete with evidence of this symbiosis, and it would not be difficult to compile a lengthy catalogue of borrowings, homages and thefts. William Caxton, for instance, who introduced the printing press in England in 1477, was an amateur translator of medieval French works, and many of the first books printed in Britain were English versions of French romances and tales of chivalry. For the printers who worked under Caxton, translation was a normal and accepted part of their duties, and even the most popular English work to be published by Caxton, Thomas Malory’s

Morte d’Arthur

, was itself a ransacking of Arthurian legends from French sources: Malory warns the reader no less than fifty-six times during the course of his narrative that the “French book” is his guide.

In the next century, when English came fully into its own as a language and a literature, both Wyatt and Surrey — two of the most brilliant pioneers of English verse — found inspiration in the work of Clément Marot, and Spenser, the major poet of the next generation, not only took the title of his

Shepheardes Calender

from Marot, but two sections of the work are direct imitations of that same poet. More importantly, Spenser’s attempt at the age of seventeen to translate Joachim du Bellay (

The Visions of Bellay

) is the first sonnet sequence to be produced in English. His later revision of that work and translation of another du Bellay sequence,

Ruines of Rome

, were published in 1591 and stand among the great works of the period. Spenser, however, is not alone in showing the mark of the French. Nearly all the Elizabethan sonnet writers took sustenance from the Pléiade poets, and some of them — Daniel, Lodge, Chapman — went so far as to pass off translations of French poets as their own work. Outside the realm of poetry, the impact of Florio’s translation of Montaigne’s essays on Shakespeare has been well documented, and a good case could be made for establishing the link between Rabelais and Thomas Nashe, whose 1594 prose narrative,

The Unfortunate Traveler

, is generally considered to be the first novel written in the English language.

On the more familiar terrain of modern literature, French has continued to exert a powerful influence on English. In spite of the wonderfully ludicrous remark by Southey that poetry is as impossible in French as it is in Chinese, English and American poetry of the past hundred years would be inconceivable without the French. Beginning with Swinburne’s 1862 article in

The Spectator

on Baudelaire’s

Les Fleurs du Mal

and the first translations of Baudelaire’s poetry into English in 1869 and 1870, modern British and American poets have continued to look to France for new ideas. Saintsbury’s article in an 1875 issue of

The Fortnightly Review

is exemplary. “It was not merely admiration of Baudelaire which was to be persuaded to English readers,” he wrote, “but also imitation of him which, at least with equal earnestness, was to be urged on English writers.”