Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. (34 page)

Read Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. Online

Authors: Viv Albertine

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

I start bleeding heavily on the coach when we’re going to recce a location.

That’s weird, it’s not my period, I never bleed in between periods

. Something’s not right. I discreetly ask a girl if she has any tampons.

Anal’s ears prick up: ‘What’s going on? What are you talking about?’

‘I’ve started my period,’ I say, to shut him up.

The nastier he is to me, the clumsier I become. I keep forgetting things, I’m absent-minded. It’s not like me, I’m usually very efficient. Maybe it’s because he’s watching me all the time, hoping I’ll fail. At the end of the first week’s shooting I feel I’ve done OK. Negotiated Anal’s weirdness, and – apart from a few shots that need to be picked up – I’ve got through the insanely packed schedule. Ringing round the next morning to find out where we’re all meeting to look at a new location, I can’t reach anyone. That’s funny, surely they’re not all sleeping in? The cameraman, the location guy, the costume designer and Anal himself are unavailable. It takes a while for me to get suspicious.

‘Do you think they’re avoiding me?’ I eventually say to the Biker.

‘No, of course not,’ he replies.

Then I get a call from Anal, can I come in to the office for a chat? I dress quite sternly, a fitted jacket, white shirt, jeans and biker boots, I have the feeling I need to look strong. The Biker takes me in on his Harley and drops me outside the office.

‘I think you know what I’m going to say,’ says Anal, rubbing his bald head, like the weight of the world is crushing his skull (I wish).

‘No.’ I’m not going to make it easy for him.

‘I’m going to have to let you go.’

I’ve never heard this expression before, it takes a few seconds for it to sink in that I’ve been sacked. He says he’ll pay me the full amount for the job, but I have to sign a confidentiality clause and never speak about what’s happened.

It’s all right, no one’s died

, I tell myself as I go reeling out into a wall of horns, cars and crowds, all mushed together into the big grey blur that is Tottenham Court Road.

Anal got his wish and directed my part of the series. I watched the first one and a half episodes later that year and was happy to see he made a right pig’s ear of it.

With Anal’s pay-off I buy my first computer, an Apple Mac, and the scriptwriting programme Final Draft and start to write a feature-film script about a girl gang in Scotland in the 1970s, based on my friend Traci’s upbringing. I call it

Oil Rig Girls

.

I move in with the Biker. I sell my flat in Balham and go halves with him on his place in Ladbroke Grove. I’m living with a handsome, surfing, motorbike-riding illustrator. We’re getting married at Chelsea Register Office in June and when I go to the doctor about the bleeding, she tells me not to worry and to take it easy, I’m pregnant.

8 BABY BLUES

1991–1995

I lose the baby. It starts to go wrong when I’m at my accountant’s. I have stomach cramps and feel wet between my legs, I say I need to go to the loo. Thick juicy slices of blood slither down my legs and onto the floor. I spend ages in there cleaning it up. I go to Self-ridges to look at hats to take my mind off it but it happens again. Blood everywhere. I run out onto Oxford Street and get a taxi home. The Biker calls the doctor and they send an ambulance. How embarrassing. I’ve never been in an ambulance before. As the paramedics wheel me into the red-brick Victorian hospital on Euston Road, a couple stop to let us pass. I look up from the stretcher and say, ‘Sorry.’

The Biker stands by my hospital bed, he looks shocked. Tubes going into my arm, a tank of oxygen attached to my face with a clear plastic mask. ‘You’re so white,’ he says. I’m losing so much blood. It’s all draining out of me.

Baby’s gone. Another baby gone. Not my fault this time. I’m determined to be positive. I

will

have a baby. Nature was just telling me this one wasn’t healthy. I get on with my

Oil Rig Girls

script. I’m also co-writing a girl-gang script with a writer called Lisa Brinkworth. We’ve actually been commissioned, paid money, to write it. I’m finding it hard to concentrate though because I still feel pregnant, like baby’s been left behind after the mis carriage. I don’t tell anyone; they’ll think I’m mad. I pop up the road to Boots and buy a pregnancy test. It’s positive.

Must be a residue from the pregnancy,

I think,

probably happens after a miscarriage, still some of the pregnancy hormone left in your body

. I don’t know what I’m talking about. Should I tell the doctor? I might just be mad or a bereft lunatic. Lisa is downstairs waiting for me to start work on our girl-gang script. I call the doctor quickly and tell her I’ve just done a test and it says I’m still pregnant. ‘Probably doesn’t mean anything, sorry to bother you,’ I say. Her voice goes very stern and steady and monotonous, like a Dalek: ‘Call a taxi and go to the hospital right now.’ ‘OK,’ I say. ‘No, I mean immediately, do not even pack a bag. Do you understand? Immediately.’ Now I’m scared.

I call the Biker and he races home and tells Lisa to leave. I don’t want to go downstairs. I’m scared to say anything out loud to her, it will make the situation real. I’m scared to get off the bed. I’m scared. After a scan, the doctor at the hospital tells me I have an ectopic pregnancy, the baby’s growing in my fallopian tube, trapped in my stringy, mangled, fucked-up tube, never made it to the womb. It could rupture any second. If that had happened and I wasn’t in hospital, I’d have bled to death.

I’m knocked out and cut open and my baby and my fallopian tube are removed. I’ve lost this baby twice. The operation is more complicated and takes much longer than the surgeon anticipated so I’m heavily sedated; I come round to a man shouting angrily at me, ‘Viviane! Viviane!!’ I don’t want to come up from the bottom of the soft silt seabed I’m lying on, it’s nice and dark and quiet down here. The nurses shout angrily when you’ve been under a long time because it brings you back quicker than a soft soothing voice. You don’t respond to a seductive siren calling your name, you just float off towards the calm deep waters of oblivion. Anger rouses you, makes you passionate, fires you up. I’m wheeled back to my bed. I feel sorry for the Biker. He was young, handsome and carefree when we met and now he’s creased and haggard and in and out of hospitals all the time, living through these dramas because he’s lumbered with me. I think my body collapsed as soon as it knew it was loved.

I wake up and look down at my stomach, it’s been cut open and stapled back together with huge steel staples. It looks disgusting, like a crumpled fleshy fish’s mouth puckering right across my body. I’m getting married in two weeks’ time but my face is yellow, my eyes are red, my stomach is stapled and my baby has gone. Not quite the fairytale ending I’d imagined.

I cancel my hen night, and my oldest school friend, Paula, comes to visit me in hospital with a tub of soya ice cream instead. The Biker tries to have his stag party, playing baseball in Hyde Park, but his heart’s not in it; he leaves early, goes home and shares a spliff with his brother. I comfort myself by writing pages and pages of baby names. Arlo, Roseanna, Ariana, Frick, Freda, Ava, John … my friends are using up all the good baby names as year after year goes by and I don’t conceive … got to keep ahead of the game … ‘It’s all right, I’m OK,’ I say to Mum rather too brightly, pen and list in hand. But I can see she thinks I’ve lost the plot.

I’m very thin now, so my wedding dress has to be altered. I buy long satin gloves from a fancy shop in Bond Street, to cover my knobbly elbows.

And then it’s my wedding day.

I stay in a beautiful boutique hotel the night before. My sister has flown over from America and sits on the end of my bed and chats to me all evening. In the morning, my friend Charlie Duffy, a fantastic makeup artist, performs a miracle on me. I will never forget what she does for me today. She mixes exactly the right shade of foundation (Hospital Yellow) and paints my features back onto the death mask that is my face. She is an artist, she makes me look human, pretty even. This is not an easy thing to do when your subject has lost every spark of life and colour that makes a person attractive. My hair is swept up and dressed with fresh blue ranunculus buds. My dress is ivory, floor-length, empire-line, with silk chiffon wisps trailing from the shoulders; Grecian with a touch of Audrey Hepburn in

My Fair Lady

.

My tall, handsome cousin Richard gives me away (I’ve gone all traditional now I’ve had a brush with death). We walk slowly into Chelsea Register Office – I’m physically frail, I have to cling onto his arm for support but I’m not nervous – to the calm, wistful strains of Eno’s ‘Another Green World’. After the reception, Hubby and I go back to the boutique hotel, no making love on our wedding night for us, I’m still stapled up. Can’t even stand up straight without difficulty. So we lie on the double bed, propped up by a pile of down-filled pillows stacked against the rattan headboard, surrounded by a fresco of cherubs and doves, and watch TV. It’s the happiest day of my life.

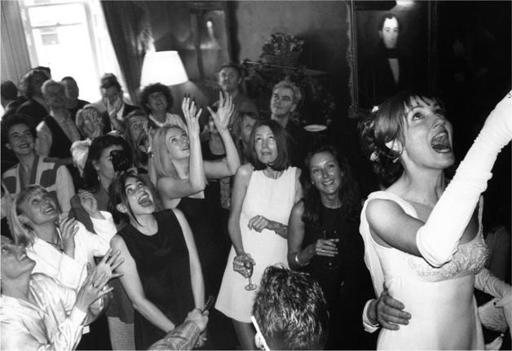

Throwing the bouquet after my wedding, 1995

9 HELL

1995–1999

Abandon all hope of fruition.

Zen saying

I turn down directing work that’s offered to me if it means being out of London for long periods of time because I want my marriage to work. Hubby works very long hours, so one of us has to compromise our career and I’m happy for it to be me. He earns more than me anyway.

Now I’ve recovered from losing the baby, we’re all geared up and committed to trying again. We’ve been told that I won’t be able to conceive naturally because my remaining fallopian tube is also mangled, so we sign up for IVF at the Lister Hospital in Chelsea.

I inject a solution into my stomach for a month to suppress my natural hormones, making me menopausal. Next I inject pregnant cow’s urine into my stomach for a month to stimulate my ovaries so they produce lots of eggs, then I’m ready for the eggs to be harvested. I make about twenty. I’ve swollen up, I look six months gone, it’s called ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, looks like elephantiasis (a teacher at my school had it). My legs, feet and waist are huge as barrels. It’s a complication, quite dangerous; I overreacted to the drugs, now I can barely walk and am constantly nauseous. My eggs are mixed with Hubby’s sperm in vitro, and the most viable three are placed back inside my womb. We wait four weeks then do a pregnancy test. I’m pregnant again.

I waddle back and forth over Chelsea Bridge to the Lister, the doctors and nurses are thrilled that it worked first time for me, but at the next appointment I start bleeding, gushing blood –

hello darkness my old friend

– and baby’s gone again.

I am wildly insanely bug-eyed crazy with grief. I don’t want to live. I think of ways to kill myself. Throw myself under this passing car? Jump off Chelsea Bridge and drown in the Thames? Or just lie face down in this puddle and stop breathing? Poor, poor Hubby, he is hitched to a raving lunatic. But he is my rock, solid, grounded, steady. I love him so much that life is just about still worth living. If it’s just going to be me and him, so be it.

We keep on going to the Lister, I keep on trying to get pregnant, months turn into years, fail after fail after fail. I am not a person, I’m a shadow, creeping along walls, quivering along pavements, my body itching, my mind wild, my patience stretched tight, ready to snap at the slightest provocation. I can’t stand to look at pregnant women. I hate them. I can’t even bear pregnant friends – I stop seeing them. If anyone walks too close to me in the street or at a bus stop, I want to kill them. I

will

kill them,

just let that fucker take one step closer, it’s nothing to me, I’m dead anyway

. My body feels like one of those diagrams you see on posters in doctors’ surgeries: skin stripped away, palms turned out, vessels, organs, arteries on show, blood raw.

Lying on the doctor’s table, week after week, my feet hoisted up in stirrups, I transport my mind outside of my body; I’m not here, it’s the woman who is longing for a baby who’s lying down there, legs wide apart with a man she’s never met before sticking his arm right up inside her.

Do it for the baby. It’s not you, Viv, you’re up on the ceiling looking down. My, she’s pale. Sweating desperation. Saddest thing I ever saw. Been crying a couple of years I’d guess. Glad it’s not me. I’m lucky. Mum always said I was a lucky baby. The nurse told her that when I was born. It’s part of my history.

At another hospital, where I’m sent for more tests, the doctor doesn’t use gloves, sticks two fingers inside me and circles them round and round inside my vagina whilst he looks into my eyes. I think it’s called abuse. When I get dressed and sit opposite him at his desk, I burst into tears. He looks petrified but I don’t report him, I haven’t got time. I’m on a mission. Next time I go to this hospital I say I don’t want him; the nurse says, ‘Don’t worry, he doesn’t work here any more.’