Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. (30 page)

Read Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. Online

Authors: Viv Albertine

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

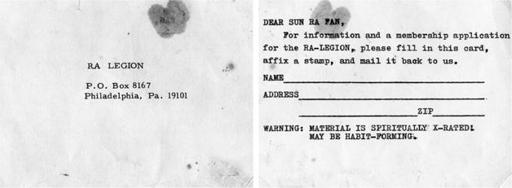

My old Sun Ra fan club application

By the time we reach Ann Arbor we’re exhausted but have to go straight to WORT Radio for an interview. Ari’s in a foul mood, she’s young and all this touring is difficult for her. As we sit down in front of the microphones, I say to Ari, ‘The only way we’re going to get through this is if we make it fun.’ Every time the interviewer asks a question, we mess around, drum on the desk and shout out the answers, luckily the DJ joins in the mayhem. Next there’s a competition, the winner gets tickets to our show tonight. The DJ asks us what the question is, I say, ‘Ask the listeners to list the colours of the stains on a girl’s knickers throughout her monthly cycle.’ Me and Ari have been talking about writing a song around this subject (‘Girls and Their Willies’), we think it could be quite beautiful. The switchboard lights up, we get loads of insults, which we laugh hysterically at, then a girl comes on the line and says, ‘White, pink, red, dark red, pink, white.’ ‘Yeah! She wins!!’

In LA we’re picked up at the airport by a big burly guy, the manager of a reggae artist we’re playing with. As he drives us to our hotel, he tells us he’s a Vietnam veteran and he’s seen some terrible things. He was in the vanguard of men who slashed and burned the villages and killed the inhabitants. He says he’s now a changed man, has discovered reggae and wants to put things right by promoting artists from Jamaica. When he laughs, his face twists into a hideous tortured death mask, full of pain. Everything he wears, his trousers, his shirt, his underwear – which we can see poking over the waistband – even his wallet, is camouflage-print. This guy is in charge of us for our stay in LA. We say we want to go to the desert, Death Valley – he takes us, says he knows how to camp out in the desert. We believe him. Off we go. The photographer Anton Corbijn comes half the way with us and takes some shots of us looking like we’re in a Diane Arbus picture – I’ve got socks tied in my hair and am holding a child’s parasol – they’re for the Christmas cover of the

NME

. We arrive in Death Valley, I can’t believe Americans come here for a holiday, it’s barren, bleak. The Vietnam vet says it takes time to see its beauty.

We set up camp and I go off to have a pee behind a cactus. I look up and see the vet a couple of feet away, staring at me pissing. He stares at me all the time; wherever I go he’s watching me. I can’t sleep, I lie on the hard ground in a sleeping bag, listening out for any movement, not of wild animals, but this madman. I thank god when the sun rises and the night’s over; the desert is freezing at night and boiling during the day. We set off back to our hotel. Driving through the endless flatness is oppressive, just white plains, they look like salt, stretching ahead of us as far as the eye can see. I discover that I’m a bit agoraphobic: I can’t bear to look out of the window, I get anxiety attacks from the nothingness, I have to look down at my lap the whole time. We wrap up in dark clothes and tie scarves around our heads, it seems the only way to protect ourselves from this relentless heat.

The photos from this trip were used as the basis for the cover of our second album,

Return of the Giant Slits.

This artwork was also by Neville Brody.

Our hotel in LA is called the Tropicana, on Santa Monica Boulevard, which is on Route 66. Jim Morrison, Rickie Lee Jones, the Byrds, Janis Joplin and Tom Waits have all stayed here, and you can feel the history oozing out of the walls. It’s the most exotic and deliciously foreign place I’ve ever seen. It’s like a building in a film noir or a Raymond Chandler novel. There’s a sign reaching way up into the sky, saying ‘Tropicana Motel’ in fake Tahiti bamboo-style lettering. Wedged underneath the hotel is an ordinary-looking cafe called Duke’s Coffee Shop. Ari says she’ll meet us at Duke’s in ten minutes, she’s going there straight away because she’s starving. She comes running to find us later, all excited because she sat next to the singer of Rose Royce for half an hour, chatting about music. We soon realise that Duke’s is the place to hang out in LA, it’s always packed and there’s always someone interesting in there. The most amazing thing about Duke’s, for me, is the breakfast. There are pancakes, bacon, maple syrup and cream squirted out of a can, cottage cheese, three types of melon, exotic fruits like mangos and kiwis, things I’ve only ever seen pictures of, all piled up on top of French toast. You never look at your plate with disappointment here, eating seems to be a penance back home but in America they make food fun.

Our first show in LA is at the Whisky a Go Go; we walk onto the stage acting like Stepford Wives because we’ve just watched the film back at the hotel and we think it perfectly describes LA – a tranquil surface with sinister undercurrents, I’m surprised how much I like it. Whilst we’re here, we try to meet up with a friend of ours called Ivi, a sweet, gentle Jamaican guy Don Letts introduced to us in London, but when we call his apartment we’re told he’s been shot dead in a drug feud. We dedicate

Return of the Giant Slits

to him.

With Ivi at Regent’s Park

57 RETURN OF THE GIANT SLITS

1981

The greater the success, the more closely it verges upon failure.

Robert Bresson,

Notes on the Cinematographer

There are two kinds of people in the ‘punk’ scene. There are the psychopathic, nihilistic extremists and careerists, who are very confident because they have no fear, lack empathy and don’t care what others think of them. The second kind are drawn to the scene by the ideas – I hope the latter will endure much longer than the first type, who are like the collaborators during the Second World War, just want to be on the side that’s winning. It’s new to me, this mercenary streak in people. I didn’t notice it in my teens, but now I’m in my twenties I see it more. Or maybe this attitude only started to rear its head after Margaret Thatcher became prime minister in 1979.

I’m doing an interview on my own with a journalist from

Melody Maker

. Halfway through, he asks me what I think of Island Records. I say, ‘I think they’re great, they really get us.’ ‘They’ve just dumped you,’ he replies. He tells me he rang Island for a quote and spoke to Jumbo, an A & R man at the label, who said we’re rubbish and they’ve dropped us. So that’s how I found out, with a journalist watching my expression keenly to see what he could write down. It’s devastating news, but I keep my composure, I’ve learnt a few tricks by now. That’s the music industry for you; no manners, no kindness, no morals, not even from a so-called ‘indie’ label.

We don’t find out why they’ve dropped us; we delivered a great album, we loved the label, got on well with Chris Blackwell: it doesn’t make sense. I tell Ari and Tessa, they’re shocked and upset too, but after a couple of days we rally and start to make plans to find another label and make another record.

We have fresh energy in the group as Neneh Cherry has joined us as backing singer and dancer – ‘vibe master’ I think the term is – and she stays with us for two years. Neneh really is lovely to be around, warm, friendly, calm and enthusiastic. Her attitude is a great help in getting us back on our feet emotionally after the Island blow.

We hear that CBS are interested in us and make an appointment with a guy called Howard Thompson. When he turns up at the cafe in Covent Garden for the meeting, I look him over. He has white-blond hair, pink cheeks and blue eyes, it can only be him: Howard Thompson from my junior school. It’s so extraordinary that we both went to this tiny little tin-pot school in Muswell Hill, it creates an immediate bond between us – he’s a lovely man, so we sign to CBS. It’s not much of a deal, but ‘punk’ has had its day already as far as the majors are concerned. We’ve already made our next album,

Return of the Giant Slits

, in different studios, bits and pieces here and there. It’s more experimental than

Cut

and brings in even wider musical influences. In some ways I think it’s a better record.

There is a mistake with the artwork, the cover comes back with the title written as

Giant Return of the Slits

. I have to argue for it to be put right, trying to explain that it really matters that it’s the Slits that are giant (either us the band, or giant vaginas), not our return. The title is based on science-fiction films and comics, like

Attack of the Fifty-foot Woman

.

Even though we love our new record, it was exhausting to make without any support and things are disintegrating within the group; the musical climate has changed in England, it’s more careerist, bands go to record-company meetings dressed in suits with briefcases and do business deals. It’s not an environment the Slits fit into at all. Honesty and outspokenness are yesterday’s papers. In the back of the van on the way to one of our last gigs Ari tells us she’s pregnant; as she talks, she tugs absent-mindedly at her eyebrows, pulling them out one by one. By the time we arrive in Bristol, she has no eyebrows left.

The Slits memorial photo, 1982. L–R: Tessa, me, Ari, Bruce Smith, Neneh Cherry

We played our last show at the Hammersmith Odeon in December 1981. It was a great show, with Neneh Cherry and Steve Beresford in the band; we were really ‘tight’, for what it’s worth. Touring America had really sharpened us up. One of our support acts was the London Contemporary Dance Theatre. I loved modern dance and wanted to give them the support slot instead of a band.

58 OVERDOSE

1981

Physician, heal thyself.

Luke 4:23

‘Wake up, Tessa!’ For fuck’s sake. I can’t believe anyone can sleep so much. It’s midday and she’s still crashed out on the sofa fully dressed. I’m so pissed off, I’m going to put a record on full blast and dance around the living room to spoil her sleep. I feel exhilarated by my naughtiness and anticipate a bit of a showdown when she wakes up. I pirouette round the room for five minutes to ‘Dancing in Your Head’ by Ornette Coleman, a deliciously annoying piece of music. I keep glancing over at Tessa to see if she’s woken up, but she doesn’t stir. I turn the music up even louder. Still nothing. I’m bored with this now, I go over and peer at her. She’s very pale, extremely white, even for her.

‘Tessa!’

I put my hand on her shoulder and shake her. She flops up and down like a rag doll. I look at the coffee table in front of the sofa, there’s an empty bottle of pills and a tiny scrap of paper, and written on it in Tessa’s elegant script is:

I’m sorry, some people just don’t have the courage

…

A feeling shoots through me but I don’t know what it is so I ignore it. What does she mean? Is it a lyric? It dawns on me: she’s taken an overdose. I have to be grown up. I have to be very calm. This is important. I think back to a party I went to when I was thirteen, a boy had taken acid and was threatening to jump out of a window. My friend’s parents were terrified, they didn’t have a clue what to do. I told them that I’d heard of an organisation called Release (founded by Caroline Coon) which gives advice on drugs, it’s non-judgemental and run by volunteers, they have a helpline that’s staffed twenty-four hours a day. The parents phoned Release and the volunteer told them what to do. This is all I can think of to do now,

no need to call an ambulance, this can’t really be anything serious. Don’t want the police coming round

. I get the telephone book and look up Release. That was so long ago, does it still exist? Yes, thank god. I tell them my friend’s on the sofa, she won’t wake up, she’s limp, there’s an empty bottle of pills. No, I don’t know what kind of pills, there’s no label. They tell me to get her on her feet and walk her round the room. I try to lift her but she’s a dead weight, I drag and pull but it’s hopeless. I call Release back and say it didn’t work.