Closing the Ring (71 page)

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #Great Britain, #Western, #British, #Europe, #History, #Military, #Non-Fiction, #Political Science, #War, #World War II

In reaching these conclusions the War Cabinet have of course had before them the telegrams sent by the Allied Commander-in-Chief [General Wilson] whose views on this subject they do not share. Meanwhile, we should be quite ready to discuss the suggestions put to the State Department by the Foreign Secretary. It is also of course recognised that should the capture of Rome be unduly protracted, say for two or three months, the question of timing would have to be reviewed.

Finally, they ask me to emphasise the great importance of not exposing to the world any divergences of view which may exist between our two Governments, especially in face of the independent action taken by Russia in entering into diplomatic relations with the Badoglio Government without consultation with other Allies. It would be a great pity if our respective viewpoints had to be argued out in Parliament and the press, when waiting a few months may make it possible for all three Governments to take united action.

This was the end of the matter for the moment.

* * * * *

Although Anzio was now no longer an anxiety, the campaign in Italy as a whole had dragged. We had hoped that by this time the Germans would have been driven north of Rome and that a substantial part of our armies would have been set free for a strong landing on the Riviera coast to help the main cross-Channel invasion. This operation, called “Anvil,” had

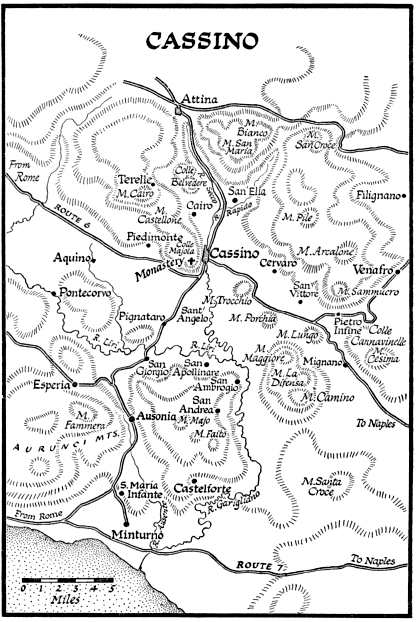

been agreed in principle at Teheran. It was soon to become a cause of contention between ourselves and our American Allies. The campaign in Italy had obviously to be carried forward a long way before this issue arose, and the immediate need was to break the deadlock on the Cassino front. Preparations for the third battle of Cassino were begun soon after the February failure, but the bad weather delayed it until March 15.

This time Cassino town was the primary objective. After a heavy bombardment, in which nearly a thousand tons of bombs and twelve hundred tons of shells were expended, our infantry advanced. “It seemed to me inconceivable,” said Alexander, “that any troops should be left alive after eight hours of such terrific hammering.” But they were. The 1st German Parachute Division, probably the toughest fighters in all their army, fought it out amid the heaps of rubble with the New Zealanders and Indians. By nightfall, the greater part of the town was in our hands, while the 4th Indian Division, coming down from the north, made equally good progress and next day were two-thirds of the way up Monastery Hill. Then the battle swung against us. Our tanks could not cross the large craters made by the bombardment and follow up the infantry assault. Nearly two days passed before they could help. The enemy filtered in reinforcements. The weather broke in storm and rain. Our attacks gained ground, but the early success was not repeated, and the enemy were not to be overborne in the slogging match.

I wondered why we did not make flank attacks to dislodge the enemy from positions which had twice already proved so strong.

Prime Minister to General Alexander

20 Mar. 44

I wish you would explain to me why this passage by Cassino, Monastery Hill, etc., all on a front of two or three miles, is the only place which you must keep butting at. About five or six divisions have been worn out going into these jaws. Of course, I do not know the ground or the battle conditions, but, looking at it from afar, it is puzzling why, if the enemy can be held and dominated at this point, no attacks can be made on the flanks. It seems very

hard to understand why this most strongly defended point is the only passage forward, or why, when it is saturated [in a military sense], ground cannot be gained on one side or the other. I have the greatest confidence in you and will back you up through thick and thin, but do try to explain to me why no flanking movements can be made.

His answer was lucid and convincing. It explained the situation in words written at the moment, and is of high value to the military historian:

General Alexander to Prime Minister

20 Mar. 44

I reply to your telegram of March 20. Along whole main battle-front from Adriatic to south coast there is only Liri Valley leading direct to Rome which is suitable terrain for development of our superiority in artillery and armour. The main highway, known as Route Six, is the only road, except cart-tracks, which leads from the mountains where we are into Liri Valley over Rapido River. This exit into the plain is blocked and dominated by Monte Cassino, on which stands the monastery. Repeated attempts have been made to outflank Monastery Hill from the north, but all these attacks have been unsuccessful, owing to deep ravines, rocky escarpments, and knife-edges, which limit movements to anything except comparatively small parties of infantry, who can only be maintained by porters and to a limited extent by mules where we have managed under great difficulties to make some mule-tracks.

Further, Monastery Hill is cut off almost completely from north by a ravine so steep and deep that so far it has proved impossible to cross it. A wider turning movement is even more difficult, as it has to cross Mount Cairo, which is a precipitous peak now deep in snow. The Americans tried to outflank this Cassino bastion from the south by an attack across the Rapido River, but this, as you know, failed, with heavy losses to the 34th and 36th Divisions. The Rapido is difficult to cross south of Cassino owing to flood-water at this time of year, soft, marshy ground which adds to problems of bridging, lack of any roads to bring up bridging material, and to the strength of enemy’s position on far bank. Again, a crossing of the Rapido River south of Cassino, as already proved, comes under very heavy enfilade artillery fire from German gun positions tucked away at foot of the mountains immediately behind or west of Cassino, and also from foothills of mountains on south of Liri Valley.

Freyberg’s attack was designed as a direct assault on this bastion, success depending on crushing enemy resistance by surprise and an overwhelming concentration of fire-power. The plan was to rush Cassino town and then to flow round the east and southern slopes of Monastery Hill and take the bastion by storm from a direction where enemy’s artillery could not seriously interfere with our movement. It very nearly succeeded in its initial stages, with negligible losses to us. We got, and still have, two bridges over the Rapido River, one on Highway Six and the other over railway bridge; both are fit for tanks. The Gurkhas got and are still within two hundred to three hundred yards of the monastery. That we have not succeeded in taking our objective within first forty-eight hours may be summarised as follows:

The destruction caused in Cassino to roads and movement by bombing was so terrific that the employment of tanks or any other fighting vehicles has been seriously hampered. The tenacity of these German paratroops is quite remarkable, considering that they were subjected to the whole Mediterranean Air Force plus the better part of eight hundred guns under greatest concentration of fire-power which has ever been put down and lasting for six hours. I doubt if there are any other troops in the world who could have stood up to it and then gone on fighting with the ferocity they have. I am meeting Freyberg and the Army Commanders tomorrow to discuss the situation.

If we call it off, we shall hold on to the two bridges and adjust our positions so as to hold the advantageous key points already gained. The Eighth Army’s plan for entering the Liri Valley in force will be undertaken when regrouping is completed. The plan must envisage an attack on a wider front and with greater forces than Freyberg has been able to have for this operation. A little later, when the snow goes off mountains, the rivers drop, and the ground hardens, movement will be possible over terrain which at present is impassable.

Prime Minister to General Alexander

21 Mar. 44

Thank you very much for your full explanation. I hope you will not have to “call it off” when you have gone so far. Surely the enemy is very hard pressed too. Every good wish.

The war weighs very heavy on us all just now.

The struggle in the ruins of Cassino town continued until the 23d, with hard fighting in attacks and counter-attacks. The New Zealanders and the Indians could do no more. We kept hold of a large part of the town, but the Gurkhas had to be withdrawn from their perch high up the Monastery Hill, where supplies could not reach them even by air because of the steep hillside.

* * * * *

In reply to my request General Wilson reported the casualties suffered by the New Zealand Corps during the battle. They totalled: 2d New Zealand Division, 1050; 4th Indian Division, British, 401, Indian, 759, 1160; 78th British Division, 190; grand total, 2400.

This was a heavy price to pay for what might seem small gains. We had however established a firm bridgehead at Cassino over the river Rapido, which, with the deep bulge made by the Xth Corps across the lower Garigliano in January, was of great value when the final, successful battle came. Here and at the Anzio bridgehead we had pinned down in Central Italy nearly twenty good German divisions. Many of them might have gone to France.

Before the Gustav Line could be assaulted again with any hope of success, our troops had to be rested and regrouped. Most of the Eighth Army had to be brought over from the Adriatic side and two armies concentrated for the next battle, the British Eighth on the Cassino front, the American Fifth on the lower Garigliano. For this General Alexander needed nearly two months.

This meant that the Mediterranean could only help the cross-Channel assault in early June, by fighting south of Rome. The United States Chiefs of Staff still strove for a subsidiary landing in Southern France, and for some weeks there was much argument between us about what orders should be given to General Wilson.

* * * * *

The story must here be told of the Anglo-American argument, first as between “Overlord” and “Anvil,” and then as between “Anvil” and the Italian campaign. It will be recalled that in my talk with Montgomery at Marrakesh on December 31, he said that he must have more in the initial punch across the Channel, and that on January 6, I telegraphed to the President that Bedell Smith and Montgomery were convinced that it was better to put in a much heavier and broader “Overlord” than to expand “Anvil” beyond what we had planned in outline before Teheran.

This was keenly debated at a conference held by General Eisenhower on January 21, shortly after his arrival in England. Eisenhower himself firmly believed in the vital importance of “Anvil” and thought it would be a mistake to impoverish it for the sake of strengthening “Overlord.” As a result of this conference, he sent a telegram to the Combined Chiefs of Staff in Washington, in which he said:

“ ‘Overlord’ and ‘Anvil’ must be viewed as one whole. If sufficient resources could be made available, the ideal would be a five-divisional ‘Overlord,’ and a three-divisional ‘Anvil.’ If insufficient forces are available for this, however, I am driven to the conclusion that we should adopt a five-divisional ‘Overlord’ and a one-divisional ‘Anvil,’ the latter being maintained as a threat until enemy weakness justifies its active employment.”

On this telegram, the British Chiefs of Staff presented their own views to Washington, namely: (

a

) That the first onfall “Overlord” should be increased to five divisions, whatever the cost to “Anvil.” (

b

) That every effort should be made to undertake “Anvil” by using two divisions or more in the assault. (

c

) That if these divisions could not be carried, landing-craft in the Mediterranean should be reduced to the requirements for a lift of one division.

The American Chiefs of Staff were unable to agree. They considered that a threat in lieu of an actual operation was inadequate and insisted on a two-divisional assault. On this telegram I minuted. “Apparently the two-division lift I

‘Anvil’ is given priority over ‘Overlord.’ This is directly counter to the views of Generals Eisenhower and Montgomery.”

* * * * *

On February 4, the British Chiefs of Staff, in full consultation with me, sent a lengthy telegram to their American colleagues, in which they emphasised that the paramount consideration was that “Overlord” should succeed and that the right solution was to build up “Overlord” to the strength required by the Supreme Commander, and then to allocate to the Mediterranean whatever additional resources could be found. They questioned the wisdom of undertaking “Anvil” at all, in view of the way things were going in Italy, and pointed out that when “Anvil” first found favour at Teheran we expected that the Germans would withdraw to a line north of Rome. But now it was clear beyond all doubt that the Germans intended to resist our advance in Italy to the utmost. They also pointed out that the distance between the South of France and the beaches of Normandy was nearly five hundred miles, and that a diversion could be created from Italy or other points just as well as through the Rhone Valley. “Anvil” in fact was too far away to help “Overlord.”

On this the United States Chiefs of Staff proposed that the issue should be decided at a conference between General Eisenhower, who would be their representative, and the British Chiefs of Staff. To this we readily assented, but several weeks were to pass before agreement was reached. General Eisenhower was still reluctant to abandon “Anvil,” but he was beginning to doubt whether it would still be possible to withdraw trained divisions from Italy. On March 21, General Wilson was asked for his opinion. He said he was strongly opposed to withdrawing troops from Italy until Rome had been captured, and he advised that “Anvil” should be cancelled and that we should only land in the South of France if the Germans cracked.