Closing the Ring (31 page)

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #Great Britain, #Western, #British, #Europe, #History, #Military, #Non-Fiction, #Political Science, #War, #World War II

6. I fully agree with all you say about the paramount importance of the build-up in Italy, and I have given every proof of my zeal in this matter by stripping the British Middle Eastern Command of everything which can facilitate General Eisenhower’s operations, in which we also have so great a stake.

To this the President replied:

President Roosevelt to Prime Minister

9 Oct. 43

The following message has been sent to Eisenhower:

“The Prime Minister in a message to the President expresses the fear that the repetition to you of the President’s message of October 8 to the Prime Minister would be taken as an order from the President and as closing the subject finally. The Prime Minister desires that it be made clear to you that the Conference scheduled

for today in Tunis is free to examine the whole question in all its bearings and should report their (your and General Wilson’s) conclusions to the President and the Prime Minister through the Combined Chiefs of Staff. The Prime Minister asks that the Conference shall give full, free, patient, and unprejudiced consideration to the whole question after having heard the Middle East point of view put forward by its representatives.

“The President directs that the foregoing desire expressed by the Prime Minister be accepted for your guidance.”

At this critical moment of the Conference, information was received that Hitler had decided to reinforce his army in Italy and fight a main battle south of Rome. This tipped the scales against the small reinforcement required for the attack on Rhodes. Wilson reported:

General Wilson to Prime Minister

10 Oct. 43

I received your message before Conference at Tunis yesterday. I also had a talk with Cunningham and Alexander. I agree that our Rhodes plan as it stood was on such a scale as to incur risk of failure. It might have been worked at the moment of the Armistice, but unfortunately some days earlier our shipping resources had been removed and the fleeting opportunity found us powerless to act.

2. Since then conditions have changed to the extent that an assault of a single brigade group followed up by one other brigade four days later would risk having both flights defeated in detail if bad weather intervened. If the forces which at yesterday’s Conference we all agreed are now necessary were to be made available, this would be at the expense of “Overlord” in landing-craft and of Alexander’s offensive in ships, landing-craft, and aircraft. The conditions in Italy also having changed materially according to latest information received yesterday, I could but agree that Alexander’s operations ought to have the whole of the available resources.

3. This morning John Cunningham, Linnell, and I reviewed the situation in the Aegean on the assumption that Rhodes would not take place till a later date. We came to the conclusion that the holding of Leros and Samos is not impossible, although their maintenance is going to be difficult, and will depend on continued

Turkish co-operation. I am going to talk to Eden about this when he arrives on Tuesday. In any case, the problem of evacuation of the garrison would be one of extreme difficulty, and we hope it may never arise. Our tenancy in the Aegean has hitherto caused the enemy to divert considerable forces in attempts to turn us out.

I replied at once:

Prime Minister to General Wilson

10 Oct. 43

Cling on if you possibly can. It will be a splendid achievement. Talk it all over with Eden and see what help you can get from the Turk. If after everything has been done you are forced to quit, I will support you, but victory is the prize.

Although I could understand how, in the altered situation, the opinion of the generals engaged in our Italian campaign had been affected, I remained—and remain—in my heart unconvinced that the capture of Rhodes could not have been fitted in. Nevertheless, with one of the sharpest pangs I suffered in the war I submitted. If one has to submit, it is wasteful not to do so with the best grace possible. When so many grave issues were pending, I could not risk any jar in my personal relations with the President. I therefore took advantage of the news from Italy to accept what I thought—and think—to have been an improvident decision, and sent him the following telegram, which, although the first paragraph is also recorded elsewhere, I now give in full:

Former Naval Person to President Roosevelt

10 Oct. 43

I have now read General Eisenhower’s report of the meeting. The German intention to reinforce immediately the south of Italy and to fight a battle before Rome is what General Eisenhower rightly calls “a drastic change within the last forty-eight hours.” I agree that we must now look forward to very heavy fighting before Rome is reached instead of merely pushing back rearguards. I therefore agree with the conclusions of the Conference that we cannot count on any comparative lull in which Rhodes might be taken, and that we must concentrate all important forces available on the battle, leaving the question of Rhodes, etc., to be reconsidered,

as General Eisenhower suggests, after the winter line north of Rome has been successfully occupied.

2. I have now to face the situation in the Aegean. Even if we had decided to attack Rhodes on the 23d, Leros might well have fallen before that date. I have asked Eden to examine with General Wilson and Admiral Cunningham whether with resources still belonging to the Middle East anything can be done to regain Cos, on the basis that Turkey lets us use the landing-grounds close by. If nothing can be worked out on these lines, and unless we have luck tonight or tomorrow night in destroying one of the assaulting convoys, the fate of Leros is sealed.

3. I propose therefore to tell General Wilson that he is free, if he judges the position hopeless, to order the garrison to evacuate by night, taking with them all Italian officers and as many other Italians as possible and destroying the guns and defences. The Italians cannot be relied upon to fight, and we have only twelve hundred men, quite insufficient to man even a small portion of the necessary batteries, let alone the perimeter. Internment in Turkey is not strict, and may not last long; or they may get out along the Turkish coast.

4. I will not waste words in explaining how painful this decision is to me.

* * * * *

To Alexander I said:

Prime Minister to General Alexander

10 Oct. 43

You should now try to save what we can from the wreck. … If there is no hope and nothing can be done, you should consider with General Wilson whether the garrison of Leros should not be evacuated to Turkey or perhaps wangled along the coast after blowing up the batteries: efforts must also be made to withdraw the Long Range Desert Groups who are on other islands. This would be much better than their being taken prisoners of war and the Italian officers executed.

And to General Wilson:

Prime Minister to General Wilson

14 Oct. 43

I am very pleased with the way in which you used such poor bits and pieces as were left you.

Nil desperandum.

* * * * *

Nothing was gained by all the overcaution. The capture of Rome proved to be eight months distant. Twenty times the quantity of shipping that would have helped to take Rhodes in a fortnight were employed throughout the autumn and winter to move the Anglo-American heavy bomber bases from Africa to Italy. Rhodes remained a thorn in our side. Turkey, witnessing the extraordinary inertia of the Allies near her shores, became much less forthcoming, and denied us her airfields.

The American Staff had enforced their view; the price had now to be paid by the British. Although we strove to maintain our position in Leros, the fate of our small force there was virtually sealed. Having voluntarily placed at Eisenhower’s disposal all our best fighting forces, ground and air, far beyond anything agreed at Washington in May or Quebec in August, and having by strenuous exertions strengthened the army in Italy beyond the plans and expectations of its Supreme Headquarters, we had now to see what could be done with what remained. Severe bombing attacks on Leros and Samos were clearly the prelude to a German enterprise. The Leros garrison was brought up to the strength of a brigade—three fine battalions of British infantry who had undergone the whole siege and famine of Malta

3

and were still regaining their physical weight and strength.

On the day that Cos fell, the Admiralty had ordered strong naval reinforcements, including five cruisers, to the Aegean from Malta. General Eisenhower also dispatched two groups of long-range fighters to the Middle East as a temporary measure. There they soon made their presence felt. On October 7, an enemy convoy carrying reinforcements to Cos was destroyed by naval and air action. Some days later, the Navy sank two more transports. However, on the 11th the long-range fighters were withdrawn. Thereafter the Navy once more faced conditions similar to those which had existed in the battle for Crete two years before. The enemy had air mastery, and it

was only by night that our ships could operate without crippling loss.

* * * * *

The withdrawal of the fighters sealed the fate of Leros. The enemy could continue to build up his forces without serious interference, using dispersed groups of small craft. We now know that the enemy faced a critical situation in shipping. The delay in attacking Leros was due mainly to his fears about an Allied attack in the Adriatic. On October 27, we heard that four thousand German Alpine troops and many landing-craft had reached the Piraeus, apparently destined for Leros, and early in November reports of landing-craft movements portended an attack. Concealed from our destroyers at night amid the islands, moving in small groups by day, under their strong fighter protection, the German troops and aircraft gathered. Our own naval and air forces were unable to interfere with their stealthy approach.

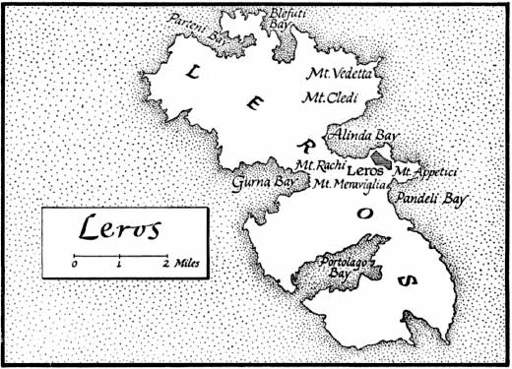

The garrison was alert, but too few. The island of Leros

is divided by two narrow necks of land into three hilly sectors, to each of which one of our battalions was allotted.

4

Early on November 12, German troops came ashore at the extreme northeast of the island, and also in the bay southeast of Leros town. The attack on the town was at first repulsed, but that afternoon six hundred parachutists dropped on the neck between Alinda and Gurna Bays, and cut the defence in two. Previous reports had stated that the island was unsuited for paratroop landings, and the descent was a surprise. Very strong efforts were made to recapture the neck. In the last stages the garrison of Samos, the 2d Royal West Kents, had been dispatched to Leros, but all was over. They fell themselves a prey. With little air support of their own and heavily attacked by enemy aircraft, the battalions fought on till the evening of November 16, when, exhausted, they could fight no more. Thus this fine brigade of troops, who had so long defended Malta, fell into enemy power. General Wilson reported:

General Wilson to Prime Minister

17 Nov. 43

Leros has fallen, after a very gallant struggle against overwhelming air attack. It was a near thing between success and failure. Very little was needed to turn the scale in our favour and to bring off a triumph. Instead we have suffered a reverse of which the consequences are only too easy to foresee. … When we took the risk in September, it was with our eyes open, and all would have been well if we had been able to take Rhodes. Some day I trust it will be our turn to carry out an operation with the scales weighted in our favour from the start.

I had read the telegrams as they came in day after day during my voyage to Cairo with deep feelings. I now replied:

Prime Minister to General Wilson

18 Nov. 43

Thank you for your messages about Leros. I approve your conduct of the operations there. Like you, I feel this is a serious loss and reverse, and like you I feel I have been fighting with my hands

tied behind my back. I hope to have better arrangements made as a result of our next Conference.

* * * * *

With the loss of Leros all our hopes in the Aegean were for the time being ended. We tried at once to evacuate the small garrisons in Samos and other islands, and to rescue survivors from Leros. Over a thousand British and Greek troops were brought off, as well as many friendly Italians and German prisoners, but our naval losses were again severe. Six destroyers and two submarines were sunk by aircraft or mine and four cruisers and four destroyers damaged. These trials were shared by the Greek Navy, which played a gallant part throughout.

* * * * *

To Anthony Eden, who had now returned home, I telegraphed:

Prime Minister (at sea) to Foreign Secretary

21 Nov. 43

Leros is a bitter blow to me. Should it be raised in Parliament, I recommend the following line:

One may ask, should such operation ever have been undertaken without the assurance of air superiority. Have we not failed to learn the lessons of Crete, etc.? Have we not restored the Stukas to a fleeting moment of their old triumphs? The answer is that these are very proper questions to ask, but it would not be advisable to answer them in detail. All that can be said at the moment is that there is none of these arguments which was not foreseen before the occupation of these islands was attempted, and if they were disregarded it was because other reasons and other hopes were held to predominate over them. If we are never going to proceed on anything but certainties, we must certainly face the prospect of a prolonged war.