Climbing Up to Glory (14 page)

Read Climbing Up to Glory Online

Authors: Wilbert L. Jenkins

Sometimes former slaves, against the determined efforts of owners to prevent them from leaving, left nonetheless and scoffed at predictions that they would return. One man, determined to keep his slave against his will, whipped him “till de blood come.” He then said, “Now you change yo' mind and give up?” But the slave said no and left with his family.

29

One woman, realizing that her freed slaves were all going, predicted, “Ten years from today, I'll have you all back 'gain.” But sixty years later, one of her former slaves noted happily, “Dat ten years been over a mighty long time, an' she ain' got us back yet, an' she is dead an' gone.”

30

Compared to field hands, rural domestics or house servants were said to have had easy chores and to have enjoyed congenial relations with their masters. But they, too, departed at an astonishing rate, a fact that puts to rest the myth of the faithful old family servant who remained loyal throughout the Reconstruction years. The myth is based on only a few recorded incidents. Patty's story is one. A black woman who served the John Berkeley Grimball family for thirty-six years before emancipation, Patty stayed with them after the war for several months, sometimes feeding the now-impoverished family with her own food. To do so, she often went hungry herself. When she eventually decided to leave, she made sure that all the clothes were washed, gave presents to the young ladies of the house, and left two of her younger children to wait on the family.

31

Some whites were deeply hurt when slaves who they thought were faithful or for whom they felt great affection suddenly departed. “I have never in my life met with such ingratitude,” a South Carolina mistress exclaimed when a former slave ran off.

32

“Something dreadful has happened dear Diary,” a Florida woman wrote in May 1865. “My dear black mammy has left us.... I feel lost, I feel as if someone is dead in the house. Whatever will I do without my Mammy?”

33

The mass defection of rural domestics threw many white households into disarray. Eliza Andrews, a Georgia woman, complained that it seemed to her “a waste of time for people who are capable of doing something better to spend their time sweeping and dusting while scores of lazy negroes that are fit for nothing else are lying around idle.”

34

Even more disturbing, as a North Carolina woman put it, was their “impudent and presumin' ” new manners.

35

Did this rude behavior mean that blacks wanted social equality? Former slaves perceived the situation differently. Their newfound freedom gave them the right to come and go as they pleasedâand also the right to act disrespectfully toward whites. It was a new day.

For many blacks, particularly women, clothing took on a larger social significance during the Reconstruction period. Black women, even those who had never attended school, gave up their old plain and drab dresses and wore more colorful and stylish garments. A perceptive statement on the role of women's clothes during the transition from slavery to freedom is offered by Rossa Cooley, a New England white woman who taught on the Sea Islands in the early twentieth century. According to Cooley,

Slavery to our Islanders meant field work, with no opportunity for the women and girls to dress as they chose and when they chose. Field workers were given their clothes as they were given their rations, only the clothes were given usually as a part of the Christmas celebration, “two clothes a year,” explained one of them as she remembered the old days. With the hunger for books very naturally came the hunger for clothes, pretty clothes, and more of them! And so with school and freedom best clothes came out and ragged clothes were kept for the fields. Work and old “raggedy” clothes were ... closely associated in the minds of the large group of middle-aged Island folk.

36

When freedom arrived, black husbands took pride in buying fashionable dresses and silk ribbons, pretty hats, and delicate parasols for their womenfolk. When a white landowner in Louisiana scolded one of his tenants for spending the proceeds of his cotton crop on clothing, which the landowner regarded as “the greatest lot of trash you ever saw,” the black man stood his ground. He told his employer that “he and his wife and children were satisfied and happy. What's the use of living if a man can't have the good of his labor?”

37

Since “insolent” behavior and stylish clothing defied the traditional code of Southern race relations, many whites were deeply concerned about the freedwomen's more expressive dress. For example, a Freedmen's Bureau officer stationed in Wilmington, North Carolina, in the fall of 1865 remarked to a Northern journalist that “the wearing of black veils by the young negro women had given great offense to the young white women, ”who consequently gave up this form of apparel altogether.“

38

The connection between insolent behavior and elaborate dress was often made, particularly by white city dwellers. Henry W. Ravenel, a white Charlestonian, described a typical street scene in the mid-1860s. In his opinion, it was “so unlike anything we could imagine.” He went on to imply that there was more than a casual connection between the two: ”Negroes shoving white persons off the walkâNegro women dressed in the most outré style, all with bells and parasols for which they have an especial fancyâriding on horseback with Negro soldiers and in carriages.“

39

The forsaking of deference plus the presence of black troops signaled an imminent struggle over “social equality” in the minds of apprehensive whites. This was a battle that could prove costly to fight and devastating to lose.

With emancipation, many rural blacks headed for Southern towns and cities in the belief that freedom was “free-er” there. They were drawn to numerous schools, churches, fraternal societies, and other black social institutions. Also in the cities were the Freedmen's Bureau and occupying Union soldiers, offering blacks a measure of protection from the violence of whites that pervaded much of the rural South. Moreover, some blacks migrated to cities and towns in search of relatives from whom they had been separated during slavery as well as in search of jobs that they believed would be plentiful. Not all these black migrants, however, experienced a significant improvement in their economic and social life but instead were witness to disease, starvation, poverty, and death.

40

And, not surprisingly, they were often subjected to white racism and racial discrimination. Still fervently believing in black inferiority, whites throughout the South were incensed over the black migration. One young white asserted in 1865 that he would leave the country before he would “live in a city where I have got to mix with free niggers.” A white woman declared: “My old Mama who nursed me is just like a mother to me; but there is one thing that I will never submit to, that the Negro is our equal. He belongs to an inferior race.”

41

As expected, black migration also heightened racial tensions and increased the economic problems facing both blacks and whites since there already existed an overabundance of labor. Blacks arriving barefoot, with ragged clothes on their backs, congregated in sections of cities that were rife with unsanitary conditions and disease. As a result, thousands of freedmen perished, and the death rate among them was staggering. A Freedmen's Bureau agent in Charleston vividly described a neighborhood occupied by poverty-stricken blacks: “Much suffering prevails among the old and infirm Freedmen. They have been suffered in some circumstances to congregate in abandoned buildings, where they are dragging out a miserable existence, suffering extremely from lack of food, clothing, fuel, proper quarters and medical attention.”

42

As concern for the suffering of black migrants rose, black men and women working through their own initiative or through northern freedmen's aid societies worked tirelessly to alleviate the suffering. As early as 1862, Elizabeth Keckley, a confidante of Mary Todd Lincoln, helped start the Contraband Relief Association. This organization became the Freedmen and Soldiers Relief Association of Washington after black men were enrolled in the army. Owing to many contributions throughout the war, it was able to continue providing food, clothing, housing, and medical attention to the needy.

43

Working on his own initiative, the Reverend Richard Cain, a future member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Charleston, played a leading role in obtaining health care for freedmen arriving in Washington, DC, and also helping them to secure employment.

44

In addition, Harriet Jacobs and her daughter Elizabeth expended much time and energy to relieve the suffering of freedmen in Arlington, Virginia, and Savannah, Georgia, through the New York Society of Friends. Harriet Jacobs was so adamant in her determination to improve the status of freedmen that in 1868 she went to England to solicit funds for a home for orphans and aged blacks in Savannah. She hoped to eventually build an asylum on about fifteen acres of land, which would give the freed people the opportunity to grow their own vegetables and fruit and keep poultry. Jacobs thanked British friends for their contributions in an appeal published in the

AntiSlavery Reporter.

In her opinion, their support was “noble evidence of their joy at the downfall of American slavery and the advancement of human rights.”

45

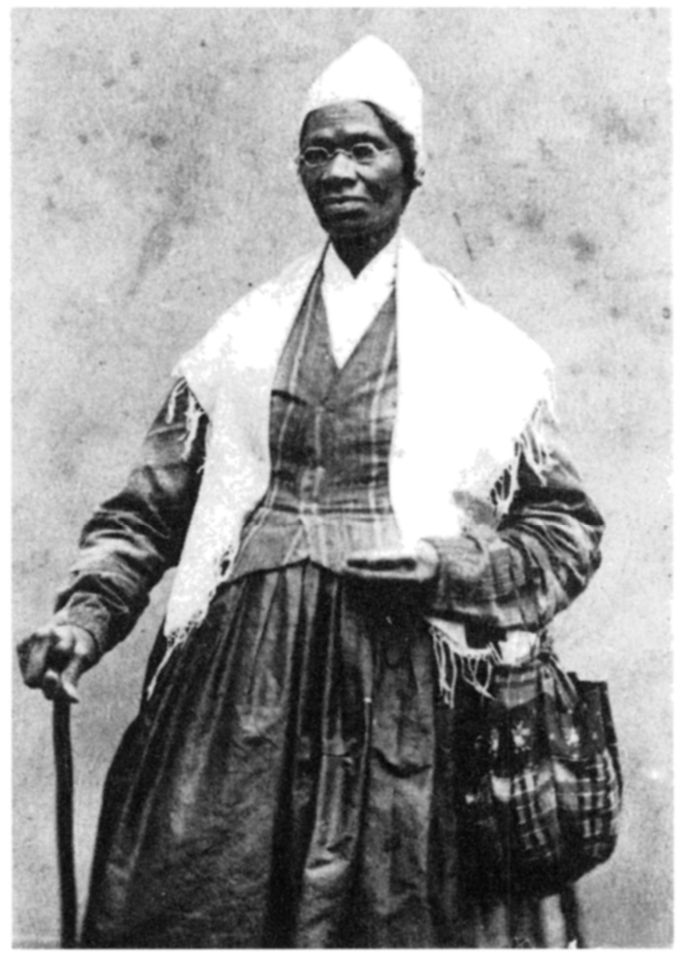

SOJOURNER TRUTH, A RENOWNED ABOLITIONIST AND POLITICAL AND SOCIAL ACTIVIST.

Library of Congress

Both Sojourner Truth and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper were deeply concerned about the plight of black people and worked long hours for the benefit of their race. In an effort to assist freedmen in Washington, DC, Truth opened an employment office. She also sought to put pressure on city officials to stop spending huge sums on imprisoning vagrants. Instead, she noted, “officials could use the funds to provide adequate money and education for Freedmen.”

46

The intensity of Truth's efforts to uplift her race was matched by Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. While acting as an ambassador to the white South, Harper spent most of her time with freed blacks. She informed William Still that “I meet with a people eager to hear, ready to listen.”

47

Sometimes Harper would speak twice per day at no charge, and part of her lectures were directed to women. She particularly preached against men who physically and emotionally abused their wives. It was necessary for black men to treat their women with the utmost respect and with sensitivity because they had been ill treated under slavery, Harper insisted. Perhaps the following statement expresses the sentiments of numerous blacks such as Elizabeth Keckley, Richard Cain, Harriet and Elizabeth Jacobs, and Sojourner Truth on the need to promote the interests of the race. Harper noted: “I belong to this race, and when it is down I belong to a down race, when it is up I belong to a risen race.”

48

Indeed, this commitment represents long-standing traditions of solidarity and self-help among North American blacks. It also epitomizes a shining moment in the struggle of blacks in the post-Civil War period for dignity and self-respect.

Despite the efforts of blacks and Northern white Freedmen's Aid societies, however, the mass sufferings of black migrants continued. The response of Federal officials to this migration often ran counter to the interests of blacks. In Richmond, for example, U.S. Army officers adopted the strategy of forcing freedmen to return to work on the plantations. In return the government would provide rations to the farmers who employed them. The ranking commander in the area, Major General J. Irvin Gregg, was instructed by his superior to “do all in your power to prevent the able-bodied men from deserting the women and children and old persons.” When practicable, migrants also should be sent back to plantations. Moreover, sentinels who were posted on the roads to Richmond were ordered to turn back all freedmen attempting to reach the city. The head of the Freedmen's Bureau in Virginia directed “all destitute persons, white and colored, who have come in from the country... to return to their homes where there is abundance of work and where work will provide food.”

49

Owing to the fact that the military controlled distribution of the rations, it was able not only to encourage but also to virtually compel blacks to reenter the workforce by returning to their families and former owners.

Military officials repeated this strategy in cities throughout the South. For instance, in Charleston, freedmen were mistreated by those whose protection they had sought. Some were arbitrarily arrested and brutalized by occupation troops; others had their food rations suspended by the Freedmen's Bureau. In June 1865 the commander of Charleston's occupation force, Colonel William Gurney, issued a warning to the large number of freedmen who had congregated in the city: they must return to the farms. When they failed to take his advice, “he asked ward committees to report the names of all able-bodied idle-persons so that they might be put to work on the streets.” Any unemployed freedmen whom Bureau officials found at large were designated as vagrants, denied food rations, and removed from Charleston. In this way the Bureau hoped to stem the overwhelming tide of black migration to the city.

50

Apparently, most officials considered this the most plausible way of dealing with an overabundance of urban labor coupled with massive hunger and disease. From their perspective, the government simply lacked the resources to materially provide for all the black migrants; and to do so ran against the basic tenets of capitalism. It would give rise to a lazy and dependent group of freedmen. Since, in the minds of many, most freedmen already possessed these deplorable characteristics, why should government policy make matters worse?

If Federal officials thought that their efforts would lead to a significant reduction in the number of black migrants, they were badly mistaken. The exodus of blacks from rural areas to cities and towns continued unabated. After emancipation, the black population of Southern cities and towns increased substantially. For example, Memphis's black population rose by 450 percent between 1860 and 1865. In addition, by 1866, Charleston had a black majority; and from 1860 to 1880, Savannah's black population grew so substantially that it constituted 51 percent of the city's total population. Other cities also experienced dramatic increases in their black populations. By 1870, Atlanta, Richmond, Montgomery, and Raleigh had black populations totaling close to 50 percent. Overall, during the 1860s, the urban black population increased by 75 percent, and the number of blacks in small rural towns grew as well. The case of Demopolis, Alabama, illustrates the latter trend. In 1860, Demopolis had only one black resident. However, at the conclusion of the war it became the site of a regional Freedmen's Bureau office; as a result, blacks began to trickle into the town. They came in such large numbers that by 1870, Demopolis had a black population of nearly one thousand.

51

Although most freedmen migrated to either Southern cities or towns, some rejected the region entirely. Instead, they sought their fortunes in the North. While it is true that the North was not yet the beacon of Southern black hopes and aspirations that it would become in the first decades of the twentieth century, 68,000 blacks relocated to these states during the 1870s.

52

Why did freed people not migrate to Northern cities in more significant numbers? Apparently, most of them regarded migration as neither feasible nor desirable. Regardless of acute white racism and racial discrimination, the South was home to most blacks, and they were determined to remain there. Furthermore, they were now free and no longer had to steal away to the North to achieve their freedom.

While large numbers of rural blacks took to the road in pursuit of “real freedom,” many former slaves, such as Charlie Davenport and a woman named Adeline who was scolded by other blacks for not leaving, stayed at the homesteads of their former owners, often for several years after the war.

53

For example, Daddy Henry proved faithful to his owner, Edward J. Thomas of Georgia. As he was getting ready to depart for battle, Thomas told Henry that everything was being placed in his care. Daddy Henry replied, “Mas' Ed, fore God I won't betray you.” He protected Thomas's family and helped them take refuge in Savannah when the fighting came too close. He lived with the Thomas family for several years after the war.

54

In a similar case, Captain W. M. Davidson, leaving Savannah in the December evacuation, asked his slave, who would be free the next day, “Take care of my wife while I am gone, will you?” The slave agreed and resided with the Davidson family for many years after the war.

55

Some of those who left eventually returned, but not out of affection for “Old Massa.” They may have been driven by “an instinctive feeling that the old cabin in which they had labored so long ought by right to belong to them,” or they hoped to find some means of livelihood among familiar people. Most who returned settled on neighboring plantations rather than on those of their former owners. Freedom was the major goal, and most did not believe that they could be free and still work under the supervision of their former owners. Freedom had to be held apart from them.