Climbing Up to Glory (13 page)

Read Climbing Up to Glory Online

Authors: Wilbert L. Jenkins

“FREE AT LAST”

The Shackles Are Broken

Â

Â

Â

Â

WHEN UNION TROOPS began to steadily advance into Southern territory, many planters fled into the interior or beyond, taking their slaves with them to safer ground. Slaveowners were particularly concerned about the real possibility of their slaves running to Union lines or being negatively influenced by Northern troops. Thus, slaves had to be moved as a precaution: “We was all taken down to DeSoto, a place near Vicksburg, for safe keeping,” recounted James Brittian.

1

George Washington Miller explained the fact that his owner, Dr. P. W. Miller, “got so uneasy about the Yankees” when the Northern Army got as near as Memphis, “that he sent us children, the Miller and Youngs, back to South Carolina in wagons trying to keep the Yankees from stealing us.”

2

Henry Butler and a number of slaves were transported to Arkansas by their master in 1863 to prevent their capture by Federal soldiers.

3

And Allen Manning recalled that his owner “tried to evade the Northern army during the war.... When we would be going down the road we would have to walk along the side all the time to let the wagons go past, all loaded with folks going to Texas.”

4

Owners also took steps to reduce the opportunities that slaves would have to run to Union lines. In Charleston, South Carolina, for example, municipal officials prohibited slaves from fishing in certain parts of the harbor, rigorously enforced the curfew, and required passports for anyone wishing to get in or out of the city.

5

Such efforts were futile, however, for slaves continued to abandon their masters in alarming numbers. The sweet taste of freedom proved too alluring. Having convinced themselves that genuine affection was felt for them by most slaves, owners were appalled by these desertions. Many were embittered and felt betrayed when their slaves continued to run away to join the Yankees. In fact, they became so angry at the loss of their property that they sought reprisals. The frequency with which slaves were whipped dramatically increased, and others were brutally murdered. Still, many of the blacks remained undaunted. As more and more Northern troops appeared, slaves became more aggressive in their attitudes toward Southern whites. They organized insurrections, set fire to houses, and beat and murdered their masters.

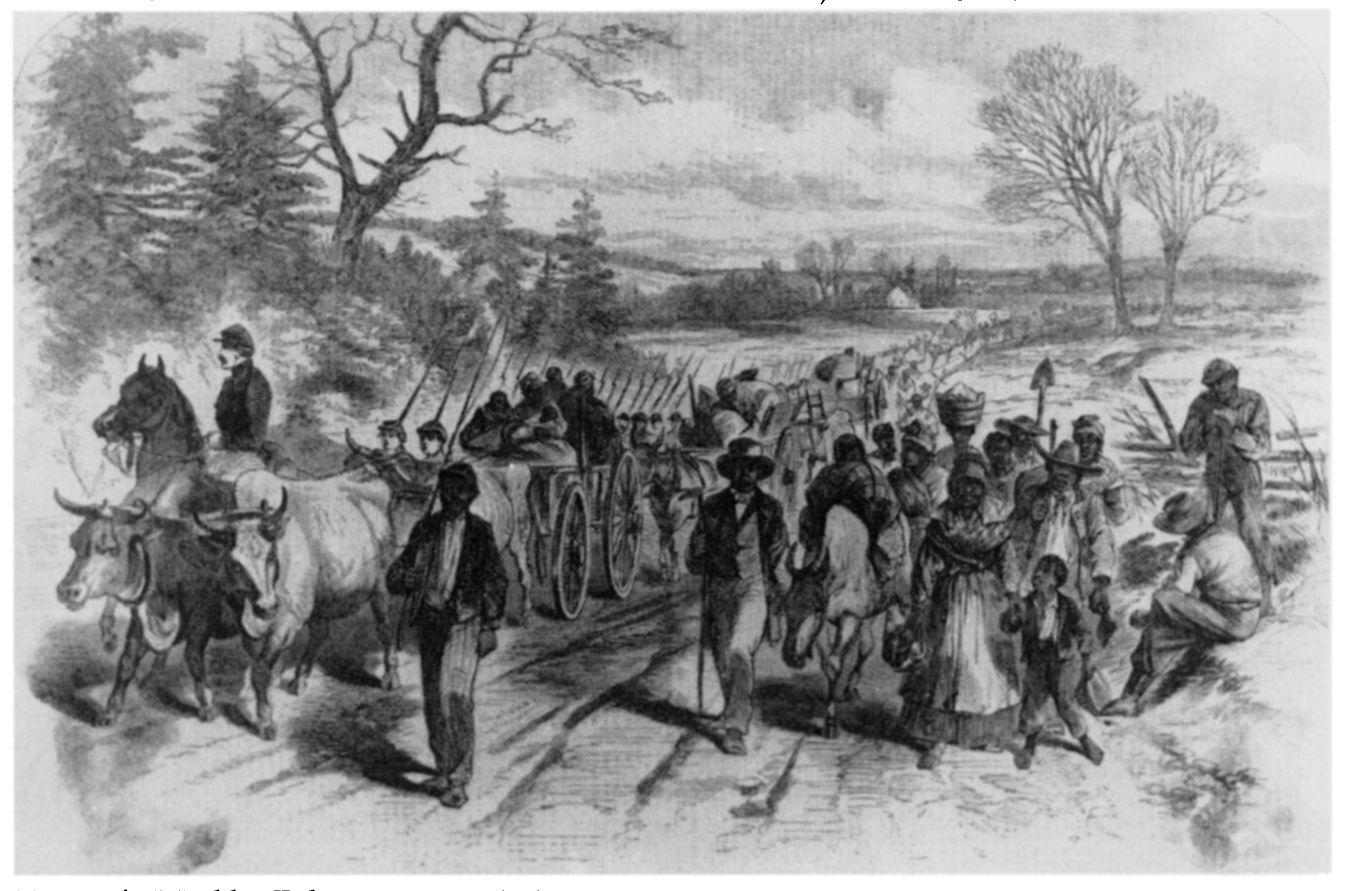

FUGITIVE SLAVES COMING INTO UNION LINES AT NEW BERN, NORTH CAROLINA.

Harper's Weekly

, February 21, 1863

An uprising was plotted in June 1861 in Monroe County, Arkansas. According to the plan, blacks would murder all white males; and, if they encountered resistance, women and children were also to be killed. Fortunately for the whites, the plot was discovered and several slaves were arrested; two men and one girl were subsequently hanged.

6

During the spring and summer of 1863 in Mississippi, where the slave population was particularly dense, there occurred new outbreaks of violence.

7

And a

New York Times

reporter commented on the surge of black unrest in the parishes of southern Louisiana during the summer of 1862: “There is an uneasy feeling among the slaves. They are undoubtedly becoming insubordinate, and I cannot think that another sixty days can pass away without some sort of demonstration.”

8

The same reporter wrote three weeks later that the slaves in two nearby parishes were in a state of “semi-insurrection.”

9

The correspondent of the

New York Herald

, writing from New Orleans, concurred: “There is no doubt that the negroes, for more than fifty miles up the river, are in a state of insubordination.” He concluded that “the country is given to pillage and desolation,” for “the slaves refuse obedience and cannot be compelled to labor.”

10

Indeed, some of the reports of black insubordination may have been baseless, the result of white fear and anxiety. However, black retaliation against whites was often very real. For instance, slaves in Yazoo City, Mississippi, in June 1864 burned a section of town that encompassed fourteen houses and the courthouse. Commenting on the incident, a reporter from the

Mississippian

remarked that “it was with great difficulty that the negroes were kept from burning it [Yazoo City] when the enemy were there before.”

11

Whites in New Orleans were especially disturbed by the frequency with which police arrested blacks for insulting and even assaulting their owners. According to the

Picayune

, “a savage old nigger named Ben, forgetting all past benefits conferred upon him, was brought into court for insulting his mistress.”

12

Slaves on a plantation in Choctaw County, Mississippi, in 1864 inflicted five hundred lashes on their master. Not far from this thrashing, David Pugh, a planter, and his overseer were assaulted by slaves who refused to work. But at least the two men shared a better fate than did General Dillard, a planter in Lynchburg, Virginia, who was murdered by five of his slaves, who were put to death by hanging.

13

In another Virginia case, in Alexandria, slaves killed an overseer who had a reputation for abusing young slave girls. Again, Southern whites made certain that those accused paid the ultimate price, as all six of the assailants were put to death. White Alexandria was particularly shocked by the heinous nature of the crime. Stephen Williams, a former slave, vividly described it: “One night they slip out and catch de overseer and kill him and tie a plowshare to the body to weight it down and throw him in the river.”

14

This aggressive behavior toward Southern whites did not emerge out of thin air. Rather, it represented a degree of continuity in slave behavior dating back to the colonial period. Rumors of insurrections were in abundance in the 1600s and 1700s throughout what was then English America. An uprising of serious proportions took place in New York City in 1712, and another near Charleston, South Carolina, in 1739. The 1800s witnessed slave insurrections led by Gabriel Prosser in Richmond in 1800, Denmark Vesey in Charleston in 1822, and Nat Turner in Southampton, Virginia, in 1831. There were also individual cases of blacks murdering whites. For instance, Lewis Bonner's father became a legend to a large number of blacks near Palestine, Texas, because he allegedly killed twenty-five whites before he was captured and put to death.

15

Once Northern troops began to appear in the South in large numbers, circumstances were much more conducive to black retaliatory action. Thus, the frequency of black violence dramatically increased. Blacks had tasted the sweetness of freedom, and they ultimately would be able to digest it once the Union Army triumphed and their shackles were broken.

Slaves freed by the Emancipation Proclamation and Union victory did not all rejoice and leave their homes spontaneously. Most slaveowning families in rural areas determined when and whether to announce the news of emancipation to their slaves. Thus, many of them remained unaware of their new status long after they were legally free. “Massa didn't tell us we's free till a whole year after we was,” remarked one former slave.

16

Union troops passing through rural areas or stationed in the cities and towns confirmed and helped to enforce black freedom. “We's diggin' potatoes,” a former slave from Louisiana and Texas recalled, “when de Yankees come up with two big wagons and make us come out of de fields and free us. Dere wasn't no cel'bration âbout it. Massa say us can stay couple days till us âcide what to do.”

17

Some rural slaves learned of their freedom when they accompanied their master to town on some errand and carried the news back to the plantation. Often body servants of Confederates returning from the war would spread the news. One such servant recalled, “All de slaves crowded âroun me an' wanted to know if dey wus gonna be freed or not an' when I tol' âem dat de war wus over an' dat dey wus free dey wus all very glad.”

18

Most rural slaves, though excited by the news, did not hastily leave the plantations. Instead, they waited until they could make concrete plans and then either left or remained on their own terms. With emancipation, they themselves now had the right to choose what they wanted to do with their lives. On the Elmore Plantation near Columbia, South Carolina, six days after the initial announcement of freedom, slaves made plans to depart. “Philis, Jane and Nelly volunteered to finish Albert's shirts before they left,” Grace Elmore recalled. “Jack, the driver, will stay till the crops are done.”

19

On David Harris's plantation in the Spartanburg district, only one man left immediately, on August 15. The others decided to remain until New Year's Day.

20

Some rural slaves may have moved cautiously out of fear. Once Union soldiers left an area, Confederate troops would often return, bringing masters and overseers with them. Thus, slaves learned not to rejoice too quickly or too openly. “Everytime a bunch of Noâthern sojers would come through,” recalled one slave, “they would tell us we was free and we'd begin celebratin'. Before we would get through somebody else would tell us to go back to work, and we would go.”

21

Another slave recalled celebrating emancipation “about twelve times” in one North Carolina county.

22

Before long, the uncertainty of when to claim freedom evaporated.

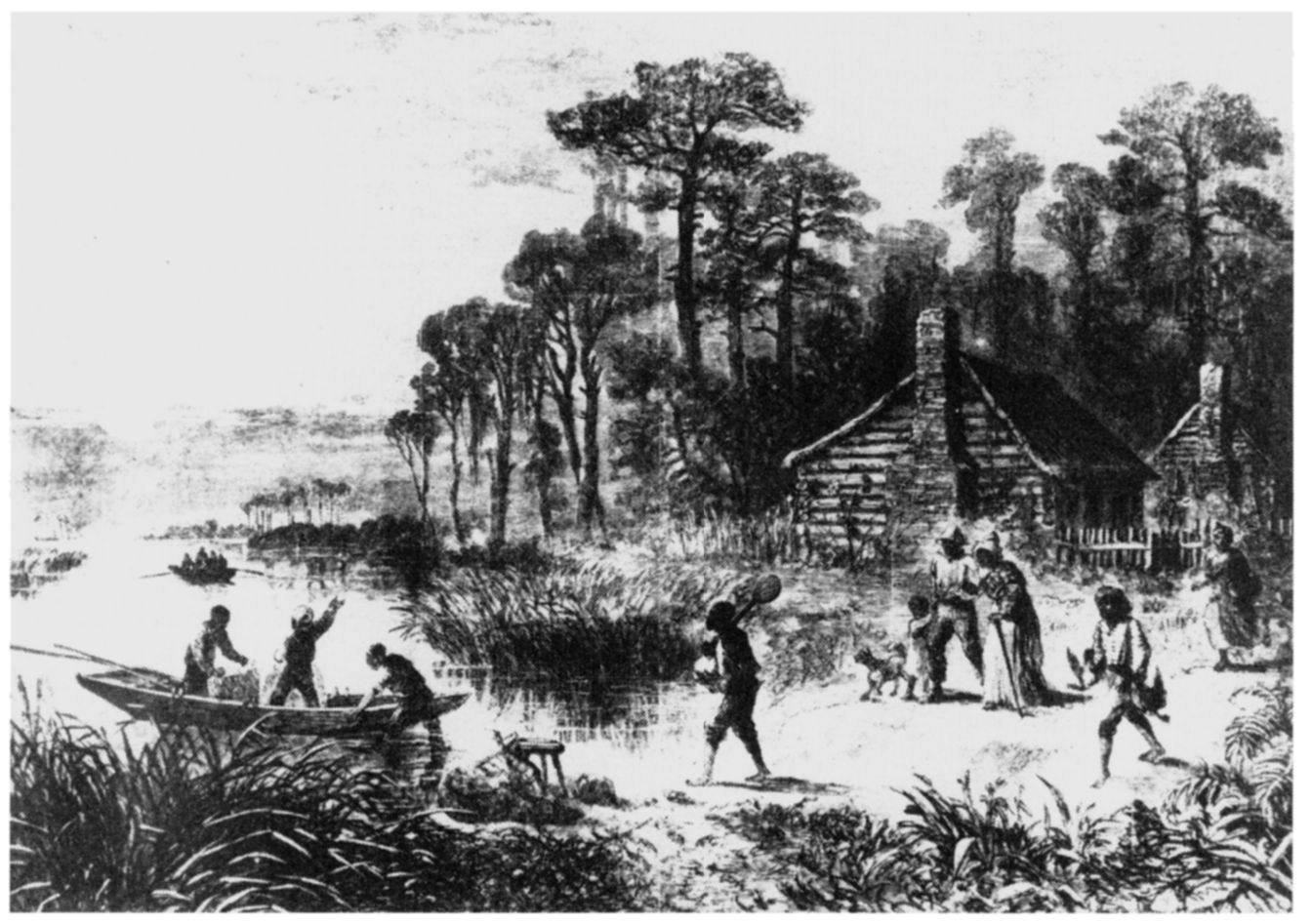

SLAVES ESCAPING TO FREEDOM BY BOAT.

Harper's Weekly,

April 19, 1864

Although their timing varied, most rural blacks ultimately chose to leave the farms and plantations of their former owners. These places were constant reminders that they had had no freedom of mobility. As slaves, blacks could not travel without a written pass and were restricted to a nine-oâclock curfew. If they were caught in violation, they were usually sent to the workhouse and whipped. With emancipation, blacks now possessed the ability to come and go as they pleased, and one of their first actions was to test this new freedom by traveling around the South. “I's want to be free man, cum when I please, and nobody say nuffin to me, nor order me roun',” one Alabama black told a Northern journalist after Appomattox.

23

“Right off colored folks started on the move,” a Texas freedman recalled,

24

and Mississippian Charles Moses declared, “I didn't spec' nothin' outten freedom âseptin' peace an' happiness, an' the right to go my way as I please.”

25

Former slaves were so adamant in their determination to test their new freedom that even those with supposedly kind owners left the plantations. For example, a Virginia planter reported that some of his former slaves “came up with tears in their eyes to shake hands with me and say good-bye.” When he reminded them that he had always treated them well and asked why they wanted to leave, they replied politely, “we bleege to go, sahâ, we bleege to go, Massa.” Of his 115 slaves, all but four or five departed when they heard that they were free. Only those who were either old or sick remained.

26

When a family in South Carolina with a reputation for kindness offered their cook higher wages than she would earn at her new job, she still decided to leave. “I must go,” she said. “If I stays here I'll never know I'm free.”

27

In Florida a black preacher advised all the slaves of a kind owner to leave: “So long as the shadow of the great house fall across you, you ain't going to feel like no free man and no free woman.” Furthermore, he added, “you must all move to new places that you don't know, where you can raise up your head without no fear of master this and master the other.” They all chose to go.

28