Cleopatra (32 page)

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

The bereaved Juba married Glaphyra, the widowed daughter of Archelaos of Cappadocia (who, rumour maintained, was the natural son of Mark Antony), but the marriage proved highly unsatisfactory – the bride was in love with someone else – and they divorced, childless, soon after. Juba appointed his son Ptolemy co-regent in

AD

21 and died in

AD

23. He was buried at Caesarea alongside Cleopatra Selene in the circular mausoleum known today as the Kubr-er-Rumia (also known as the Tombeau de la Chrétienne).

Ptolemy of Mauretania inherited his father’s throne. His personal history is ill-recorded, but it seems that he married a lady named either Urania or Julia Urania, and that he had a daughter, Drusilla, who married Marcus Antonius Felix, procurator of Judaea during the reign of Claudius. In

AD

40 Ptolemy was executed on a trumped-up charge by his half-cousin Caligula. Suetonius tells us that his ‘crime’ was to wear a robe more splendidly purple than Caligula’s own.

9

It is perhaps more likely that Ptolemy, ‘son of King Juba and descendant of king Ptolemy’, was suspected of plotting against Rome, although Caligula, notoriously unstable, hardly needed an excuse to execute people.

Looking back from the historian’s perspective, we can see that the death of Cleopatra VII heralded the death of the Hellenistic age and the birth of Imperial Rome, which led in turn to the birth of the modern western world. Octavian, appreciating this point, renamed

the eighth month (Sextilis) after himself, because it was both the month when he received the title ‘Augustus’ and the month in which ‘Imperator Caesar [Octavian] freed the commonwealth from a most grievous danger’: Alexandria had fallen on I August. The vast majority of the Egyptian people were, of course, unaware of this; for them, life continued much as it had before and much as it would for centuries to come. Rule by a Ptolemy or a Roman, a pagan, Christian or Muslim, it made little difference.

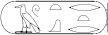

Other conquerors had tailored their behaviour to the beliefs of their new country and had continued the tradition of royal rule supported by the gods. But Octavian, confident of his military strength and, perhaps, averse to the idea of hereditary kingship, saw no need to pander to the Egyptians. Thousand years of royal rule came to an abrupt end as he claimed Egypt as his own personal estate. Technically kingless, although the Egyptian priests would continue to give their Roman overlords cartouches and titles, and to depict them in traditional Egyptian style, Egypt was to be administered by the relatively lowly Cornelius Gallus, a prefect of the equestrian rank. Egyptians would not be allowed to serve in the Roman army, or to enter the Senate; Romans wishing to visit Egypt would need to obtain permission from Octavian. Octavian embarked on a tour of his new property, inspecting canals and irrigation ditches. Intent on suppressing the eastern cults and unconcerned about offending the local priests, he refused to visit the Apis bull, announcing to anyone who would listen that he worshipped gods, not cattle. Presumably he neither knew nor cared overmuch that Egypt’s priests were already depicting him as a pharaoh participating in the traditional animal cults.

As Rome moved into Egypt, Egyptian culture started to invade Rome. Egyptian artefacts were suddenly all the rage and, in a move guaranteed to confuse the archaeologists of the future, the Romans started to import both genuine and fake Egyptian antiquities. Now sphinxes and obelisks stood, slightly self-consciously, alongside the

statues of noble Romans that adorned the public squares. In the Field of Mars in Rome, a Late Period Egyptian obelisk even served as the gnomon for a gigantic sundial:

Augustus [Octavian] used the obelisk in the Campus Martius in a remarkable way: to cast a shadow and so mark out the length of the days and nights. An area was paved in proportion to the height of the monolith in such a way that the shadow at noon on the shortest day would reach to the edge of the pavement. As the shadow shrank and expanded, it was measured by bronze rods fixed in the pavement.

10

Cleopatra’s treasure – now Octavian’s treasure – was taken to Rome, where it was used to finance Octavian’s political career. The statue of Victory that Octavian erected in the new Senate House was decorated with Egyptian spoils, as were the Capitoline temple of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva and, appropriately perhaps, the temple of the Divine Julius. For Dio, this made a fitting end to a turbulent tale:

Thus Cleopatra, though defeated and captured, was nevertheless glorified, inasmuch as her adornments repose as dedications in our temples and she herself is seen in gold in the shrine of Venus.

11

Cleopatra had a jazz band

In her castle on the Nile

Every night she gave a jazz dance

In her queer Egyptian style …

J. Morgan and J. Coogan, ‘Cleopatra Had a Jazz Band’

1

T

hree hundred years after her death, Cleopatra-Isis was still being worshipped at Philae. Her image would remain on Egypt’s coins for decades and on her temple walls for thousands of years. But this version of Cleopatra the queen and wise mother goddess was confined to Egypt. In the wider Mediterranean world the well-oiled Roman propaganda machine continued to manipulate public opinion against Cleopatra long after the battle of Actium.

Octavian was determined that his own personal history should be recorded for posterity in a way that justified his not always heroic actions and confirmed his god-given right to rule; a difficult matter for a self-proclaimed republican to explain. To achieve this, he not only published his own autobiography, he edited, and in some cases

burned, Rome’s official records. Much of his propaganda – the ephemeral jokes, graffiti, pamphlets, private letters and public speeches – has of course been lost. But enough remains to allow us an understanding of the corruption of Cleopatra’s memory.

As Cleopatra had played a key role in Octavian’s struggle to power, her story was allowed to survive as an integral part of his. But it was to be diminished into just two episodes: her relationship with Julius Caesar and, more particularly, her relationship with Mark Antony. Caesar, the adoptive father who gave Octavian his right to rule, was to be remembered with respect as a brave and upright man who manipulated an immoral foreign woman for his own ends. Antony, Octavian’s rival, was to be remembered with a mixture of pity and contempt as a brave but fatally weak man hopelessly ensnared in the coils of an immoral foreign woman. Cleopatra, stripped of any political validity, was to be remembered as that immoral foreign woman. Almost overnight she became the most frightening of Roman stereotypes: an unnatural female. A woman who worshipped crude gods, dominated men, slept with her brothers and gave birth to bastards. A woman foolish enough to think that she might one day rule Rome, and devious enough to lure a decent man away from his hearth and home. This version of Cleopatra is, of course, the precise opposite of the chaste and loyal Roman wife, typified by the wronged Octavia and the virtuous Livia, just as Cleopatra’s exotic eastern land is the louche feminine counterpoint to upright, uptight, essentially masculine Rome. As public enemy number one, Cleopatra was extremely useful to Octavian, who not unnaturally preferred to be remembered fighting misguided foreigners rather than decent fellow Romans.

The most vivid near-contemporary interpretation of Cleopatra is a fictional account. When, in 29, Publius Vergilius Maro started work on his twelve-volume

Aeneid

, he determined to create a modern epic in the style of Homer’s

Odyssey

(Books 16) and

Iliad

(Books 712) that would both glorify Rome and celebrate Octavian’s rule. Aeneas, son

of the goddess Venus and founder of Rome, was to be equated with Octavian, descendant of Venus and of Aeneas and founder of the Roman Empire. Underpinning the first part of

The Aeneid

is the tragedy of Dido and Aeneas. The eponymous hero, fleeing by boat from devastated Troy, is desperate to reach his ancestral homeland but runs into a storm and washes ashore on the North African coast. Here he meets Dido, founder and queen of Carthage, who is compelled by the gods to fall in love with him. The two go through a form of marriage, which Dido recognises as legally binding but Aeneas, it soon transpires, does not. Happy in their love for each other, they forget the outside world. But Aeneas is a strong moral character, obedient to the will of the gods. Faced with the choice between pleasure and duty he chooses duty, and deserts the queen:

‘I know, O queen, you can list a multitude of kindnesses you have done me. I shall never deny them and never be sorry to remember Dido while I remember myself, while my spirit still governs this body. Much could be said. I shall say only a little. It was never my intention to be deceitful or run away without your knowing, and do not pretend that it was. Nor have I ever offered you marriage or entered into that contract with you.

’

2

Furious and despairing, Dido curses her former lover, then commits suicide rather than face life alone.

Parallels with the stories of Julius Caesar (a strong man who put duty above pleasure) and of Antony (a lesser man than Aeneas/Caesar/Octavian who was tempted by a foreign queen and found wanting) are obvious. Dido, a woman who willingly enters into a pseudo-marriage and who is ultimately destroyed by her own guilt, is to be equated with Cleopatra. Virgil is, however, relatively sympathetic to Dido, whose life has been deliberately destroyed by the gods. Less sympathetic to Cleopatra is his anachronistic reference to Aeneas’s

intricate shield, forged by Vulcan, which features Octavian’s victory at the battle of Actium:

On the other side, with the wealth of the barbarian world and warriors in all kinds of different armour, came Antony … With him sailed Egypt and the power of the East from as far as distant Bactria, and there bringing up the rear was the greatest outrage of all, his Egyptian wife! … The queen summoned her warships by rattling her Egyptian timbrels – she was not yet seeing the two snakes there at her back – while Anubis barked and all manner of monstrous gods levelled their weapons at Neptune and Venus and Minerva.

3

Faced with such a glorious image, Virgil’s readers might perhaps forget just how weak Octavian’s military record actually was.

The subversive Augustan poet Sextus Propertius writes longingly of his feisty mistress Cynthia. He, like Mark Antony, has been ensnared and to a certain extent emasculated by a powerful woman, and he is not afraid of admitting it. Answering the question, ‘Why do you wonder if a woman controls my life?’ he lists examples of famous, unnaturally dominating women, including the Amazon Penthesilea, Omphale, queen of Lydia, Semiramis and, of course, Cleopatra, ‘the whore queen of Canopus’. Later he provides a somewhat tongue-in-cheek tribute to Octavian and the battle of Actium. Clearly Propertius is aware of the irony of a Roman man celebrating a great victory over a mere woman, but, like Virgil before him, he sensibly sees no need to labour this delicate point.

4

In this he is joined by his contemporary Horace, who is happy to reduce Cleopatra to the status of a madwoman drunk on power, yet who also gives a surprisingly sympathetic account of her death: ‘fiercer she was in the death she chose, as though she did not wish to cease being queen’.

5

By restoring some of Cleopatra’s dignity, Horace actually makes her a more credible and worthy foe for Octavian.

Rome’s historians, writing later than the poets, preserve a more rounded impression of Cleopatra. She is seductive and unnatural, yes, but we also catch glimpses of an educated, even intelligent woman. But history, in Rome, was not the strict discipline that it is (or should be) today. Sparse historical ‘facts’ were woven into a coherent narrative with large helpings of personal opinion and guesswork. Stories were selected in order to make a moral or political point. And, of course, the Roman historians concentrated on Cleopatra’s interaction with the Roman world while ignoring her life in Egypt. The two most influential of Cleopatra’s ‘biographers’ are Plutarch and Dio; from their works come the Cleopatras described by later classical authors. The Roman writer Suetonius (

The Divine Julius

and

The Divine Augustus

) and the somewhat unreliable Alexandrian Greek Appian (

The Civil Wars

) add further to Cleopatra’s tale.