Cleopatra (31 page)

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

26. Octavian: The Emperor Augustus. Bronze statue recovered from the Aegean Sea.

It is therefore not surprising that, when lost on his way to the oracle of Zeus-Ammon, Alexander was guided on his way by talking snakes. Even the infant Heracles, ‘ancestor’ of Mark Antony, Alexander the Great and the Ptolemies, had a run-in with a pair of snakes sent by Hera to kill him.

Octavian had allowed Cleopatra to organise Antony’s funeral as she wished:

though many generals and kings asked for his body that they might give it burial, Caesar [Octavian] would not take it away from Cleopatra, and it was buried by her hands in sumptuous and royal fashion, such things being granted her for the purpose as she desired.

22

We are not told what form this burial took. During the first century

BC

Roman burial customs varied from region to region, with inhumation being preferred in the eastern empire and cremation in the west. Antony, as a western Roman, may therefore have expected to be cremated, and indeed Plutarch writes of Cleopatra ‘embracing the urn which held his ashes’, and again, ‘she wreathed and kissed the urn’.

23

Plutarch may, of course, have been succumbing to his own cultural expectations. The fact that Cleopatra was able to visit Antony in his tomb a mere twelve days after his death suggests that he had not been mummified, as mummification was a lengthy practical and sacred ritual, taking seventy days. However, the rock-cut tombs of southern Egypt, with their eclectic mix of Egyptian, Greek and Roman styles, confirm just how appealing the elaborate traditional burial customs were to Egyptians of non-Egyptian heritage. Alexander the Great is purported to have been embalmed, and the fact that the tombs of the

Ptolemies were places of pilgrimage suggests, without proving, that they too were mummified. In Alexandria, the early excavators, Evaristo Breccia and Achille Adriani, found hundreds of mummified bodies in the cemeteries of Ras el-Tin and Anfushy. All these mummies were badly decomposed and all are now lost. But the tombs have yielded coins of both Cleopatra and Augustus (Octavian), proving that inhumation preceded by mummification was practised in Alexandria at the time of Cleopatra’s death. It is interesting that no mummies are recorded for the other necropoleis of Alexandria, including the most recently excavated Gabbari cemetery, which has produced hundreds of simple interments.

Now Octavian made plans for Cleopatra’s funeral:

Caesar [Octavian], although vexed at the death of the woman, admired her lofty spirit; and he gave orders that her body should be buried with that of Antony in splendid and regalfashion. Her women also received honourable interment by his orders.

24

The joint tomb of Cleopatra and Antony is today, like all the other Ptolemaic royal tombs, lost beneath the waters of the Mediterranean Sea.

The story we are writing, and the great name of Cleopatra which figures in it, have plunged us into those reflections which displease a civilized ear. But the spectacle of the ancient world is something so overwhelming, so discouraging for imaginations that believe themselves unlicensed, and for spirits that imagine they have attained the last limits of fairy-like magnificence, that we could not refrain from registering here our complaints and regrets that we were not contemporary with Sardanapalus, with Tiglath-Pileser, with Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt, or even of Heliogabalus, Emperor of Rome and Priest of the Sun

.

Théophile Gautier,

Une Nuit de Cléopâtre

1

I

n the end, Cleopatra did process through the streets of Rome. A statue of the queen lying on her deathbed with a snake suitably attached was carried in Octavian’s triple triumph, celebrated in 29, to commemorate his defeat of various barbarians, his victory at Actium and his conquest of Egypt. Soon after, the Augustan poets Horace, Virgil and Propertius included references to Cleopatra’s death in their

works, each specifically incorporating not one but two snakes, the ‘twin snakes of death’, in their tale.

2

Later artists, Shakespeare included, accepted the idea of the two snakes and transferred their bites from the arm to the much more dramatically appropriate breast, so that the image of Cleopatra with one or two asps clasped to her bosom could be contrasted with the image of Cleopatra/Isis the mother goddess nursing her child:

Peace, peace!

Does thou not see my baby at my breast,

That sucks the nurse asleep?

3

Cleopatra died on 12 August 30.

4

Octavian formally annexed Egypt on 31 August 30. This left an eighteen-day gap when Egypt was, in theory, ruled by the sixteen-year-old Caesarion. A broken statue, said to have been recovered from Karnak in the early twentieth century and now housed in Cairo Museum, shows us Egypt’s last king: a confident but unmistakably young man with rounded, almost childish cheeks and Greek-style curls on his forehead. Cleopatra had raised her first army at twenty years of age; Arsinoë IV had commanded hers at fourteen. But Caesarion had no meaningful support and could have no thought of taking up his throne. Belatedly aware that her son’s official adult status made him vulnerable, Cleopatra had already sent him away from Alexandria. Together with his tutor, Rhodon, and part of Cleopatra’s treasure, Caesarion was to make his way to the southern city of Koptos, travel overland via the desert trade route to the Red Sea port of Myos Hormos, then board a ship for India where, if all went well, he would be reunited with his mother. But all did not go well. Soon after his mother’s suicide Caesarion was captured – Plutarch tells us that he was betrayed by Rhodon, who somehow persuaded him to return to Alexandria – and executed. Documentary evidence confirms that there was civil unrest in the Theban area immediately after

Cleopatra’s death, but it seems that this was caused by high taxes and should not be interpreted as a pro-Cleopatra or pro-Caesarion uprising.

Antyllus was also dead; decapitated as he sought sanctuary beside a statue of Julius Caesar in Alexandria. He, too, had been betrayed by his tutor, Theodorus, who was tempted by the precious stone (another part of Cleopatra’s treasure?) that he knew Antyllus concealed beneath his garments. He snatched the stone from Antyllus’s bleeding neck and sewed it into his girdle. But Theodorus was to pay dearly for his betrayal; he was caught, convicted and crucified. Antony’s other children were all allowed to survive. Iotape, the daughter of the Median king who had been brought to Egypt as the fiancée of Alexander Helios, was sent back to her family. The ten-year-old twins and four-year-old Ptolemy Philadelphos were taken to Rome, where, carrying heavy golden chains, they were displayed in the public triumph alongside the statue of their dead mother. They were then given to the virtuous Octavia to raise alongside her own children and their half-brother Julius Antonius, younger brother of Antyllus. Julius was to marry Octavia’s daughter Marcella, and would eventually be executed for alleged adultery with Octavian’s daughter Julia. Alexander Helios and Ptolemy Philadelphos vanish from the historical record soon after entering Octavia’s household and, although Dio tells us that they passed into the care of Cleopatra Selene on the occasion of her marriage, it seems perhaps more likely that they did not survive childhood.

Five years after her mother’s suicide Cleopatra Selene was provided by Octavian with a large dowry and an eminently suitable husband. She was to marry the Numidian prince Juba II, whom we last met as an infant walking in Caesar’s African triumph (page 104). The province of Numidia (Africa Nova: New Africa) lay on the north African coast, sandwiched between the province of Mauretania (modern western Algeria and northern Morocco

5

) to the west and the province

of Africa (modern Tunisia) to the east. Juba’s father, Juba I, had allied himself with Pompey, and had chosen to fight a duel to the death rather than be captured by Caesar’s forces. Taken from his homeland as an infant, Juba II had been raised in Rome, where, restyled Gaius Julius Juba, he had become a model Roman citizen and a close friend to Octavian. He accompanied Octavian on several military campaigns and fought at Actium, but he is best remembered as a serious and scholarly young man, a poet, historian, philologist and geographer who published more than fifty books written in both Greek and Latin. As a keen explorer Juba is credited with discovering the Canary Islands, and naming them after the fierce dogs (

canaria

) that he found there. His claim to have discovered the source of the Nile in the Atlas Mountains of his own land was supported by his recovery of a crocodile from the ‘source’; the crocodile was later presented as a votive offering to the temple of Isis in Caesarea.

6

Soon after the battle of Actium, Juba was sent to rule Numidia as a fully Romanised client-king. In

c

. 25, probably at the time of his marriage, he was relocated to neighbouring Mauretania, a province made prosperous by strong trade links with Italy and Spain. Fertile Mauretania exported grain, pearls, wooden furniture and fruit. A purple dye manufactured from Mauretanian shellfish was used to provide the stripes in the senatorial togas, while highly flavoured garum sauce, so popular in Rome, included large anounts of Mauretanian fish. Juba and Cleopatra Selene ruled from Caesarea, the ancient city of Iol (modern Cherchell), which they renamed to honour Augustus Caesar (Octavian). Architecture and sculpture recovered from Caesarea show a contemporary mixture of Roman architecture and Hellenistic statuary: there were baths, a temple to Augustus and a theatre designed by an acclaimed Roman architect which was later converted into an amphitheatre.

A marble portrait head, excavated from Cherchell in 1901 and now housed in Cherchell museum, shows a veiled, curly haired woman

with a prominent nose and jaw who bears a strong resemblance to Auletes. A second head, excavated in 1856, shows a more mature woman with similar facial features, a melon hairstyle, a kiss-curl fringe and a diadem. W. N. Weech, engaged on one of his ‘rambles in Mauretania Caesariensis’ in 1932, was struck by the anonymous queen’s appearance:

It is an extraordinarily expressive face – intelligent eyes, arrogant nose, firm mouth. Many of the critics suggest that this represents Cleopatra Selene; if they are right, we must abandon all romantic pictures of a Moon princess, fragrant with the mystic glamour of ancient Nile, endowed with Cleopatra’s sorcery and Mark Antony’s fire. This is the head of a woman whose will swayed her passions, a maîtresse femme, and Selene must have ruled her Juba with inflexible decision during the thirteen years of their joint reign?

7

Whether either of these heads represents Cleopatra Selene or her mother is impossible to determine.

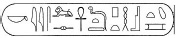

Mauretanian coinage reflects both Roman and Egyptian themes. While Juba’s coin portraits generally show a Roman-style king whose name is written in Latin (Rex Juba), Cleopatra Selene’s coins display Hellenistic Egyptian motifs with no hint of her Roman heritage. There are crocodiles,

sistra

and Isiac symbols, and Cleopatra Selene’s name and title are given in Greek so that she becomes Basilissa Cleopatra, the title used by her mother. Clearly neither Octavian nor the strongly pro-Roman Juba felt threatened by the queen’s persistent references to her Egyptian roots.

Cleopatra Selene bore a son named (of course) Ptolemy and, perhaps, a daughter who, we may guess, was named Cleopatra. She died some time between 5

BC

and

AD

11, her death being commemorated in an epigram by the poet Crinagoras, a friend and client of Octavia:

When she rose the moon herself grew dark

Veiling her grief in the night, for she saw

Her lovely namesake Selene bereft of life

And going down to gloomy Hades.

With her she had shared her light’s beauty,

And with her death she mingled her own darkness

.

8