Clara's War (26 page)

Authors: Clara Kramer

The next three days were hell. The eternal darkness in the bunker made every moment endless. With any light at all, even a candle, I could read, teach the children, sew, anything to keep my mind occupied. But now with no light except for the short time we lit the candles so we could eat and take care of our

bodily functions, I had nothing to do, none of us did, except stare at the thin blade of light coming from the air opening and pray for a swift end to the war.

I spent all my time listening to the soldiers. Norbert's voice lost its charm. I heard them talk about their wives and girlfriends and children. I heard Richard's cynicism about the war. I heard Hans screaming, âI'm fighting here and the Allies are bombing the hell out of my family!' His wife and children lived in Hamburg and he was furious at the reports of the Hamburg bombings he heard on the radio and in the news. Last year Hamburg had been firebombed by an allied armada of almost 800 planes. In the few weeks the soldiers had been here, Hamburg had been bombed three times. I hated Hans. Not only for his anti-Semitism but also because he was lazy. When he wasn't working, he spent most of his time in bed. When there was even one German in the house, we couldn't move, couldn't talk, couldn't cook, couldn't use the pail. And that German was usually Hans.

We were sitting in the dark listening to the card game go on for hours upstairs. It was a full house. Hans the policeman was drunk and happy. He had found a comrade in Hans the soldier as they swapped exploits and bragged about the number of Jews they had killed. Hans the policeman entertained the group by his most recent triumph: the Bernsteins. Mama had to listen as Hans, as loud and boisterous as a best man giving a toast at a wedding, recounted the Bernsteins begging him to spare their lives. They were refugees who lived not far from Aunt Rosa in western Poland and had come to Zolkiew in 1939. Mrs Bernstein was a relative of the Britwitzes, who had lived next door to the Melmans in one of the houses that burned down in the fire. Mrs Bernstein was born in Zolkiew and she knew Mama when they were both girls. Here the Russians were

breathing down Hans's own neck and would, God willing, be here in a matter of weeks or months, and still he took joy in finding and slaughtering Jews.

Beck had to pretend to hear it all for the first time and we heard his hearty congratulations. His sincerity at Hans's good fortune was convincing. The soldier Hans was not to be outdone and recounted the murders of each of the 75 Jews he had personally killed. He had been keeping count. The extermination of a people had been reduced to entertainment over schnapps, sausage and Julia's pirogies. I was next to Zosia, holding her. She didn't cry any more as she listened to Hans's brutal laughter and backslapping joy at his accomplishment. All she knew of life was this persecution, of people trying to kill her, of vilifying her for being something she was far too young to even understand. Her Jewishness meant nothing to her. I wanted to write. I wanted to get every word down, but there was no light so I had to listen without my blue nub of a pencil in my hand. I listened in darkness and my face had the freedom to express its grief, if only silently, and its rage, if only mute. Beck had to sit across from both murderers, deal the cards, pour the drinks, serve the food and listen, laughing, looking both men in the eye while we remained hidden. For 17 months all we had to do was hide, yet day after day, moment by moment, the Becks, and especially Mr Beck, had to lead a double life, like the most brilliant spy in the most brilliant spy novel. How he withstood the pressure was beyond me. My courage was nothing compared to his.

As soon as the soldiers and the trainmen left for work the next day, Beck came down to the bunker. He had a bottle of vodka with him and poured drinks for the men. Beck didn't say anything for a long time. âI'm sorry', he said. âI'm sorry. Please. I hope you don't think I meant what I said last night. I hope you

know I don't feel like that.' He was apologizing to us. He wanted us to know the words he spoke upstairs weren't his true self, which he only dared show us. I had so many questions to ask Beck. How was he able to keep up the front that he was a loyal

Volksdeutscher

? Where did he find the courage? How could he be so calm and natural with our enemies? I could tell he was very fond of Krueger and Schmidt. But the others? The two Hanses? Was Beck afraid? How could he control his fear? Did he have that much faith in God? Did he trust his own luck that much? But most of all, why? Why had he risked his life for us? He talked about honour sometimes. He ranted that the Ukrainians and the Germans had no right to kill Jews. But somewhere I felt there was another reason, hidden perhaps. And I hoped that some day we might have a chance to talk about it, if I ever got up enough courage to ask.

There was so much going on now I couldn't keep up with recording it all in my diary. Beck had given me the present of a new copybook and as I wrote the fresh pages were quickly covered in the sweat dripping off my face. My entries were smudged by the wet pages and it was almost impossible to write legibly. Compared to what was happening around us, a smudged page didn't seem much, but the copybook was now my most precious possession. And if we perished and if the diary was found, I didn't want one moment of the Becks' courage to go unknown.

I realized now we were in the same situation as the day of the fire. Even if there was another place to hide, we'd never make it. There had been a mob in the streets that was also filled with German soldiers, police and Blue Coats. If we had tried to flee we would have been caught in minutes. Now there were very few civilians. Soldiers were living in every house on the street. There were over 20 living in Papa's factory. And many more

were camped near the cemetery, which since the fire was in direct view of the house. We were on the main road to Lvov so military patrols and traffic were constant. There were no Poles left, so there would be no place to hide and no one to hide us if we did try to leave the bunker.

Beck told us that the Ukrainian police were collecting arms, arresting and shooting anybody they wanted and stealing Polish homes and possessions at will. And since Ala's transfer to Krakow was certain again, Beck said he was going to the forest to join the partisans. Beck was a patriot and wanted to pick up a gun and fight his country's enemies. I understood that. I felt the same way. If he said come to the partisans with me, I would have gone. I also knew Beck was hoping one of us would say, âGo. We'll be fine.' But no one said a word. Klara finally said, âGo. Go ahead. But before you do, please take your rifle and shoot us. Kill us. Please.' We had all condemned Klara for her relationship with Beck, but it was only their love affair that allowed her to speak so bluntly to Beck. And it was keeping him here with us and protected. I didn't know if he was in love with her. I didn't know if he would abandon us, but he would never abandon her. There had to be a war raging inside him. He was loyal to us, his family and his country. But he couldn't protect us all and fight as well.

He agreed to stay. We were safe for now. Beck reassured us that he would go only if Von Pappen made him. He also told Mr Patrontasch that the Russians had taken Sevastopol, Odessa and had recaptured the rest of the Crimea. Now the Russians could turn their forces north and west. I had new hope. The Russians moving their main force towards Vinnytsia, and the bombing of Lvov, had to be a prelude to a major offensive in Galicia.

The next time the Becks and the soldiers went out, Mr Patrontasch took the buckets upstairs to empty them. When he

came back down, I knew something was wrong. When he told us, every hope I had for survival vanished. Mr Patrontasch saw that the Becks had packed up all their belongings and lined them up in the hall. The man I had come to trust as much as my own father and in whom I vested all my hopes for survival had looked us straight in the eyes and lied to us. There was only one possible conclusion. They were going to leave and not tell us.

I'M LOSING HOPE

10 May to 6 June 1944

Wednesday, 10 May. Trouble again. Lang who was always saying he is staying, decided to leaveâ¦Mr Beck says he is not leaving unless they force him, but we don't know if one day he will just leave without telling us. Pappen is coming back any day. What are we going to do if Mr Beck says Pappen gave an order to go?

I

t was decided that Mr Patrontasch would talk to Beck, as he always did.

âWe were worried that you had changed your plans.'

Mr Patrontasch had a certain way with Beck. He was able to understate the most frightening things. Now he told Beck simply that we worried he might have changed his plans. Beck knew exactly what he meant and how terrified we all were.

He put our fears to rest immediately. âIf I told you I wasn't leaving, then I'm not leaving. We moved up some things from the cellar in case there's a fire, that's all. If they're bombing Lvov, they'll be here before we know it. No sense losing everything we own in a fire.'

Mania and I in our sailor suit school uniform, aged 5 and 6

With my father and Mania, 1938

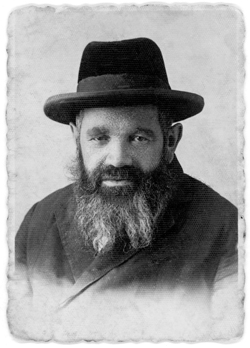

My babcia and dzadzio

The photos my friends and I took when we didn't know if we would survive the war, 1942. I am with Genya Astman (left).

Mania

From left to right: My mother Salka, (in front) Julia Beck, Fanka Melman, and (behind) an unknown friend

Lola Elefant

Klara Patrontasch and her brother Artek in the 1930s

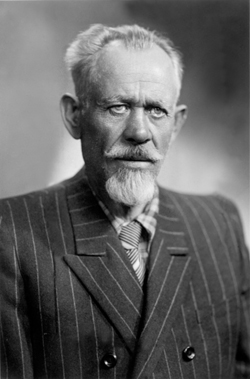

Mr Valentine Beck, after the war

Ala Beck

Myself with Mr Beck and Mr Melman, 1946

The Melman's house