Cheyenne Saturday - Empty-Grave Extended Edition (16 page)

Read Cheyenne Saturday - Empty-Grave Extended Edition Online

Authors: Richard Jessup

Caption 12...

End of the track near Humbolt River Canyon, Nevada, 1868. The Central Pacific campsite and train are at the foot of the mountains.

* * *

The first train arrived in Cheyenne in September of 1867 but nearby Laramie—a mere 50 miles away—didn’t see the Union Pacific crew come through until May of 1868. Cheyenne was a stopping point for Union Pacific workers as engineers tackled one of the biggest challenges the railroad would face—the Dale Creek Trestle. The winter of 1867-68 was spent constructing what, at the time, was the highest railroad bridge in the world.

* * *

The federal government needed to protect the rail, track-layers, and the burgeoning tent towns along the line. Fort Sanders, south of Laramie, was already in existence before the Union Pacific came through. At Cheyenne, though, Fort D.A. Russell was built with the specific purpose of protecting the railroad. The forts provided security from Indian attacks but many of the “hell-on-wheels” towns—an apt nickname for those popping up along the railhead—needed protection from themselves. The first mayor in Laramie stepped down after just three weeks because he saw the town as “ungovernable,” leaving law and order to be doled out by vigilantes and through lynchings.

* * *

Caption 13...

City of Cheyenne, Wyoming, 1876. Showing growth of a tent city along the Transcontinental line.

Caption 14...

Rock River train depot, Albany County, Wyoming, 1900. Showing growth of one of the stops along the Union Pacific portion of the Transcontinental rail line by Laramie.

Press representatives in an excursion party to 100th meridian, 275 miles west of Omaha, Nebraska, to meet with Eastern capitalists and other prominent figures. October, 1866.

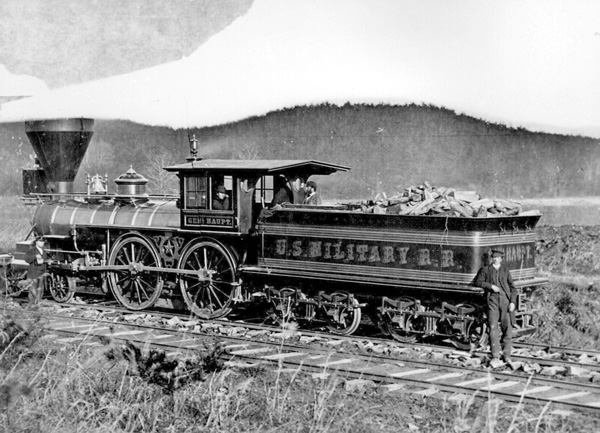

Caption 15...

Example of an early Central Pacific locomotive for the US Military. Rail transport was critical during the Civil War.

Caption 16...

Union Pacific #119. The locomotive that touched noses with Central Pacific’s #60 ‘Jupiter’ in Promontory, Utah, at the Golden Spike ceremony.

Caption 17...

Union Pacific directors on the 100th meridian awaiting the arrival of the excursion party of press reps and business men.

Caption 17b...

Union Pacific directors on the 100th meridian awaiting the arrival of the excursion party of press reps and business men.

* * *

Central Pacific’s ‘Jupiter’ (one of the two locomotives in the famous picture three pages ahead) was actually a standby. The initial choice—Diamond Stack #29 ‘Antelope’—was being towed to the ceremony by Jupiter when log-cutters mistakenly rolled a large log down a hill, striking the Antelope.

* * *

The Jupiter was a 4-4-0 steam locomotive built in September, 1868 by Schenectady Locomotive Works. It was then dismantled and sent by river barge to the Central Pacific headquarters in Sacramento. It’s inaugural run was March 20th, 1869.

* * *

Caption 18...

Sign posted shortly after the 10-mile record was set.

* * *

Eight Irish track layers—Michael Shay, Patrick Joyce, Michael Kennedy, Thomas Dailey, George Wyatt, Michael Sullivan, Edward Kieleen, and Fred McNamara—stepped up to the challenge laid out by the boastful Central Pacific promoter, Charlie Crocker. That seemingly impossible goal was to complete the railroad’s last 700 mile advance to Promontory, Utah by laying ten miles of track in a single day. Two years earlier the crew would have been lucky to put one mile down a day. Years of constant laying, though, had transformed the process into a near exact science.

* * *

On April 28th, 1869, sixteen cars of material—bolts, rails, spikes—were unloaded in eight minutes. The hardware was piled onto small railcars by six-man teams and then each car was pulled up the line by two horses and unloaded by crews of Chinese laborers. Three men aligned the wood ties to the surveyor stakes. The work was then on the backs of the eight Irish track layers—who set out each rail, hammered the eight spikes, and bolted the fishplate at the joint. Behind them, levellers lifted ties and shoveled dirt under to ensure the track was level. The gang laid 144 feet of track a minute. 3,524 rails, 28,160 spikes, 25,800 ties and 12 hours later the job was done. Each of the men had hefted 1800 rails; the eight men combined had moved two million pounds of track in half a day.

* * *

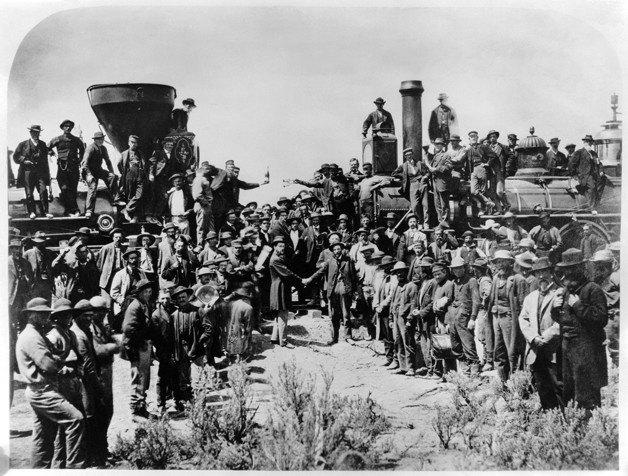

Surprisingly, the ceremony to drive the last spike (photo on next page) was not supposed to take place when and where it did. The Union Pacific and Central Pacific were racing to lay the most rail and, as a result, they converged in the undesirable Promontory, Utah, at a time when the promoters, key businessmen, and government officials could not attend the event. On May 10th, 1869, Leland Stanford of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific’s Thomas Durant each awkwardly swung the ceremonial hammer at the last spike—and missed. Two swings later the two groups performed a champagne toast in front of their representative locomotives—the #119 from Union Pacific and Central Pacific’s #60 Jupiter. Contrary to popular belief, the last “golden” spike was actually one of five that day, and the only spike that was actually driven into the tie was of the plain iron variety. The other four spikes—two solid gold, one solid silver, and one made of iron with silver on the shaft and gold plating on the head—were temporarily placed into pre-drilled holes in a laurelwood tie that was later cut up and distributed to important figures in business and the government. All five spikes currently reside in museums around the country.

* * *

Caption 19...

The Golden Spike ceremony.

Biography

*The following information was pieced together from Jessup’s obituary, used book listings on the internet, and a brief paragraph from the second edition of

Twentieth Century Western Writers

– which was then removed from later editions.

Richard Jessup (01/01/1925 – 10/27/1982) was born in Savannah, Georgia and died in Nokomis, Florida. He lived in and out of orphanages until age sixteen – when he ran away to join the United States Merchant Marine. In eleven years of seamanship, he claimed he read a book a day and learned to write by typing out the complete text of

War and Peace

and editing out the errors – he subsequently threw the edited work in the ocean. Jessup was married to Vera in 1944 and had a daughter named Marina. He left the Merchant Marine in 1948 to become a fulltime author. He was at the typewriter ten hours a day.