Chernobyl Strawberries (18 page)

Read Chernobyl Strawberries Online

Authors: Vesna Goldsworthy

My French teachers, Madame Mimitza and Madame Foni â the former blonde and almost Scandinavian in appearance, the latter Athenian by birth, with glossy dark hair and black-rimmed glasses â both seemed fantastically, unattainably French to me. In fact, they were more French than most French women ever manage to be. It takes a certain

je ne sais quoi

which only elegant women in the East seem to possess to attain that kind of Frenchness, like the teaspoonful of sugar which makes savoury foods taste more of themselves.

At one stage in my teens, I made conscious efforts to be more ladylike myself. I cut my hair in a straight bob and wore twinsets, tartan skirts and little ballet pumps in a way which pleased my mother immensely. Then I began seeing the captain of my school basketball team and went back into jeans and trainers. The captain was six foot six. I can still remember burying my nose into the middle of a big fleecy number on his team shirt smelling deliciously of sweat when we embraced after his sporting triumphs. One December evening, while I was suffering from a very bad episode of pneumonia, he came to visit me at my bedside with a fragrant little posy of dwarf violets in his enormous hands, and enquired whether I was planning to be back on my feet in time for the New Year. When I told him that such a speedy recovery seemed highly unlikely, he suggested that it might be better if we parted at that point. He wanted a girlfriend for New Year's Eve and, as I was obviously not cooperating, there was just enough time to find a new one. I was so feverish I couldn't even summon the strength to get up and kick him out of the house. One learns a lot about fair play by dating sportsmen.

I went back to French bobs and twinsets and gave up my own, admittedly not at all promising, career in high-school basketball. In the best traditions of socialist education, my school encouraged sporting prowess as much as any scientific or artistic skills. Even at the university, one couldn't sign up for exams without proof of participation at the weekly skating or swimming sessions and the annual two-kilometre race at the hippodrome. I chose shooting practice, which was more useful than skating and lacked the painful associations of basketball. By the time I met Petar, I was quite a markswoman.

My French school was, in many ways, one of the most selective institutions in socialist Belgrade. Parents were interviewed and vetted as thoroughly as prospective students. To get me and my sister a place, my father expended his entire reservoir of charm upon Madame Dora, who was in charge of admissions. He knew that his work for the army might be a drawback (it was that kind of institution), but his handsome manner won the day.

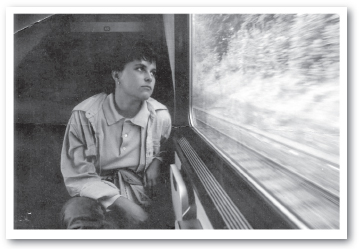

Somewhere in Europe

The school's recitals were legendary and quite a few of our classes were devoted to rehearsals and preparation. One year, I polished the lines from Aragon's

La Rose et le Réséda

until each elision and each emphasis fell in its proper place, and Madame Mimitza told me that I sounded âalmost French', the greatest compliment of all. The French ambassador and the cultural attaché always sat in the first row with representatives of the old, French-educated Belgrade elite. Even the French President, Giscard d'Estaing, turned up with his wife at one of

our performances. Each vase in the school was full of gardenias and there were trays of pastel-coloured almond mignons on every side table. The grand piano was tuned and polished for the occasion. Overexcited boys and girls in starched white collars and patent-leather shoes responded to the President's questions in deliberate, careful French. Madame Mimitza and Madame Foni hovered behind smiling anxiously.

After my first stay in Paris, paid for by the French Ministry of Culture as an award for an essay in French entitled, appropriately, âWhy I love France', I affected a Parisian accent and said things like

shai pas

instead of

je ne sais pas

, as though I was brought up in an apartment on Ile de la Cité and had not just spent three weeks in a hostel opposite Père Lachaise cemetery. How I loved France! There was never any aplomb in my boring English school, where my Anglophobe but practically minded parents sent me twice a week from the age of seven to the age of eighteen. We were confined to dire pieces about Stratford-upon-Avon and Stonehenge and the same old excerpts from Dickens again and again. The teachers did not seem to care that most of the students were interested only in things American and were adopting the most implausible American accents, picked up in local cinemas. How come I ended up on this island, speaking English all the time?

Quite what Petar, a socialist and a true egalitarian, saw in my breathless, Francophone snobbery is anyone's guess. The two of us walked, argued about politics and occasionally stopped to exchange passionate kisses. You hardly ever see people kissing like that on the streets of London, but in southern Europe, where young people continue to live with their parents throughout the years of yearning, it is a common sight. The thick, dark crowns of lime trees which lined Prince Milosh

Street were full of sparrows chirping dementedly, and the windscreens of cars parked underneath were dotted with guano, like oversized snowflakes. In late spring and early summer, the smell of exhaust fumes from battered buses mixed with the sickly fragrance of lime blossom. The street was a canyon, its walls made up of large, ugly edifices: embassy buildings, ministries and government headquarters. It was about as intimate as walking down Whitehall in London or Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington. Numerous little guards huts, no bigger than telephone boxes, lined the pavements. In some of these, policemen in tight blue uniforms sat listening to their radios or eating hotdogs. In others, young soldiers in heavy grey overcoats stood forlornly with guns on their shoulders.

Embassies of the more or less friendly socialist countries had large panels with photographs showing off economic and cultural achievements. Everyone on those panels seemed blissfully happy, but the cumulative effect was always depressing. Western embassies tended to have a folded flag in the lobby, like a forgotten beach parasol, and a large photo of their president. If the country in question was a monarchy, the display seemed more familiar: a painting of a glum middle-aged woman with a tiara, very much like Comrade Jovanka, or a finely manicured chap in an elaborate uniform, like our own Comrade Tito. Ideological differences notwithstanding, these were fellow Ruritanians.

On one of our walks, I entertained Petar with a theory, tailored entirely to suit my Francophilia, that ânice' countries had red, white and blue flags, while ânasty' ones always included yellow. This theory reflected my political maturity. I was one of those people who always read the newspapers from the back, stopping two-thirds of the way through, just after the book pages. I made a conscious effort to know as little about politics as possible.

Petar was the exact opposite. He didn't just read the newspapers, he

read

them. He knew what each minute shift in government signified, and why â in a well-rehearsed speech â Comrade So-and-So described someone as a demagogue, a technocrat or an opportunist. He knew why pauses for applause were scheduled after particular rhetorical flourishes in the speech but not after others. In those days, the most inconspicuous turns of phrase hid major power struggles. âThere are doubters in our society,' someone would announce grandly, and suddenly â as if on cue â doubters would be rooted out, fired from their jobs or sent to prison, as appropriate to the magnitude of the doubt they harboured.

Petar was also one of the first people I knew to mutter darkly about unseen powers which were working to break Yugoslavia apart. He seemed very fond of Yugoslavia. I liked the place too â it was my country, after all â but cared much less about whether its constituent parts remained together or not, so long as Belgrade went on more or less as usual. At that stage, I still believed that given the freedom to vote most Yugoslavs would vote Green and focus on cutting petrol emissions. I could not have imagined that, soon after I left the country, it would be in the hands of people like Slobodan Milosevic or Franjo Tudjman. I was barely aware that such men existed. I didn't think that anyone could be so foolish as practically to ask to be bombed by the West. Nor did I assume that the Western armies would oblige. I'd underestimated the whole lot of them.

Given that members of my wider family â to count just the non-combatants â had been murdered by soldiers belonging to at least five different nationalities in the past hundred years or so, my optimism was astonishingly naive. I never paused to worry about my relations in Sarajevo, for example. What could happen to my uncle Mladen and his

Croatian wife, or my cousin Danny and his Muslim wife? My plans for the future somehow always allowed for winters on the snow slopes around the Bosnian capital, followed by baked apples with walnuts and sour cherries in âEgypt', the best patisserie in town.

It was in âEgypt' that one of my cousins once exclaimed, laughing, âI have a fine lot of Belgrade girls here, mash'Allah.' His moustache tipped with icing sugar spread across his face, revealing a row of shiny white teeth. âAnd how much do you ask for those two sweet apples? I'll take them to Istanbul, so help me God,' retorted another beaming, moustachioed man. We tugged our cousin's sleeve in panic, worrying that he might really sell us. I now wonder whether we sold him in the end.