Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World (54 page)

Read Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World Online

Authors: Samantha Power

BOOK: Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World

2.3Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Local staff members were unaccustomed to being treated with such respect by foreigners. When Vieira de Mello held a barbecue at his house, he made sure Amaral’s whole family attended. And as he had done with Lola Urošević, his translator in Sarajevo, he never stopped asking the Timorese how they judged their economic prospects or the UN’s performance.

But for all of his sensitivity to symbols, some of his decisions sent the wrong signal to the Timorese.With the havoc wreaked by the Kosovo Liberation Army foremost in his mind, he initially urged the Timorese to disband FALINTIL, the guerrilla army that had been fighting for independence for a quarter of a century. Much as NATO had been tasked with stabilizing Kosovo, he thought that it should be the job of the Australian-led Multinational Force to keep the Timorese secure. He thought that the presence of the FALINTIL guerrillas might intimidate those Timorese who had voted in the referendum to remain a part of Indonesia and who would eventually return to their homes in East Timor. But his early idea met with an uproar, as the rebels were beloved as both the symbol of and the vehicle for the end of Indonesia’s occupation. He quickly reversed his decision, instructing the fighters to remain in their barracks, off the streets. Gusmão was angry about this edict as well, complaining that independence fighters should not be “encaged like chickens.”

17

17

On November 18, tensions over FALINTIL came to a head. The Australian force commander, General Peter Cosgrove, instructed the guerrillas to consolidate some seventeen hundred fighters in a single barracks in Aileu. The soldiers did so in a relatively orderly fashion, but one truck filled with soldiers had a flat tire on its way and decided to stop in Dili for the night. The Australian military got word of their unauthorized presence and confronted them, seizing their knives and guns.When Gusmão was roused from his bed and informed, he was outraged. “The Australians are treating my men like common criminals,” he exclaimed. “They came to Timor, they didn’t fight a single battle, the militias fled, and now they are walking around with big chests like conquerors.We fought for twenty-four years, and yet they actually think they are superior.”

Gusmão’s first task was soothing his men. “We played by Indonesian rules for all these years,” he said, as much to himself as to his fighters.“We can follow UN rules for a few more months.” But then he made a public stand. He drove to Dili with a platoon with weapons and was intercepted by General Cosgrove personally. “I don’t speak in the streets,” said Gusmão. “I’m on my way to Dili. If you want, feel free to come along.” When Cosgrove blocked the road with an Australian armored personnel carrier, Gusmão disembarked. “We are used to walking,” he said. He and his men walked the remaining several miles into town, and Cosgrove trailed on foot. Vieira de Mello was scheduled to meet with Gusmão that very morning. When he arrived amid a loud commotion, he exclaimed, “Xanana, what have you done? I thought we were going to meet to discuss our strategic plan!”

UNTAET’s symbolic mistakes kept coming. Since the hotels and guesthouses had been burned down along with everything else in East Timor, most arriving UN officials had no place to stay. At the start election officials who had stayed on slept beneath their desks at the UN compound, hanging washing lines between their offices. Unwisely, UN administrative staff arranged for two ships, known as the

Hotel Olympia

and the

Amos W,

to sail to Dili and serve as hotels for those waiting for housing. The $160-per-night rooms in the floating hotels were not grand—the ships were really nothing more than barges topped with four layers of stacked containers—but from the vantage point of the Timorese onshore, the ships looked like luxury liners, especially after a rooftop disco opened on one, blaring music into the night. Timorese nationals were initially barred from dining or sleeping on the ships, which stirred further unrest. Unemployed Timorese milled around the esplanade near the gangplanks, hoping to be hired for the going wage paid by the UN and other international employers: three dollars for a twelve-hour day.

18

The ships would become such a headache for Vieira de Mello that in July 2000 he ordered the nightclub on the ship to be closed at midnight. But by then the damage had long been done.

Hotel Olympia

and the

Amos W,

to sail to Dili and serve as hotels for those waiting for housing. The $160-per-night rooms in the floating hotels were not grand—the ships were really nothing more than barges topped with four layers of stacked containers—but from the vantage point of the Timorese onshore, the ships looked like luxury liners, especially after a rooftop disco opened on one, blaring music into the night. Timorese nationals were initially barred from dining or sleeping on the ships, which stirred further unrest. Unemployed Timorese milled around the esplanade near the gangplanks, hoping to be hired for the going wage paid by the UN and other international employers: three dollars for a twelve-hour day.

18

The ships would become such a headache for Vieira de Mello that in July 2000 he ordered the nightclub on the ship to be closed at midnight. But by then the damage had long been done.

The Timorese were jobless, homeless, and hungry. They saw few signs that their country was being rebuilt. They did not control their own destinies. And they grew angry. In December 1999 some 7,000 Timorese who were waiting in the scorching heat to be interviewed for 2,000 UN jobs learned that the jobs would go first to those who spoke English. The crowd began throwing rocks, hitting an Australian soldier in the mouth.Then they turned on Timorese who worked for the UN, beating up several and stabbing one. Only when Ramos-Horta arrived on the scene were tempers calmed.

19

The following month, at the first major demonstration against the UN, one of the protesters held up a sign that read, “EAST TIMORESE NEED FOOD AND MEDICINE, NOT HOTELS AND DISCOTHEQUES.”

20

19

The following month, at the first major demonstration against the UN, one of the protesters held up a sign that read, “EAST TIMORESE NEED FOOD AND MEDICINE, NOT HOTELS AND DISCOTHEQUES.”

20

In 2000 the UN moved from its election headquarters at the teacher training compound into the Governor’s House, a two-story colonnaded Mediterranean mansion that overlooked the ocean, which had first housed the Portuguese and then the Indonesian colonial powers. Since no other facility that was still standing could accommodate the large UN mission, Vieira de Mello moved into the same second-floor office that months before had housed the unpopular Indonesian governor.

Instead of simply departing their prior headquarters, the UN staff stripped the premises bare. In a highly literal reading of the UN rules laid down by the member states, they removed all “UN property”: not only the tables, chairs, and bulbs but also the air conditioners, cables, and wires. “Anything they couldn’t take, they broke,” recalls Padre Filomeno Jacob, who would later become Timorese education minister.“It was like vandalism.” Upon learning of the incident, Vieira de Mello personally delivered certain items back to the Timorese. But it was too late. “That’s when we realized we had to look out for ourselves,” Jacob says. “We entered the confrontation phase.” Gusmão began to refer to the UN presence as the “second occupation.”

The protests picked up steam. In February 2000 angry medical students marched in the streets demanding the right to go back to school. One fish merchant came and dumped his raw fish at the doorstep of the UN mission, protesting the lack of electricity, which had deprived him of refrigeration.

The Timorese gathered regularly to protest price hikes, and the UN’s fourteen hundred local staff staged their own strikes over pay.

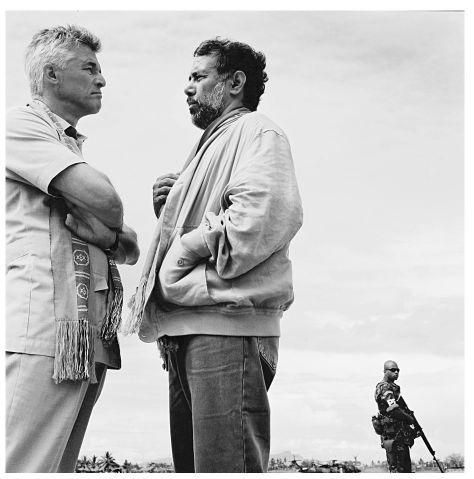

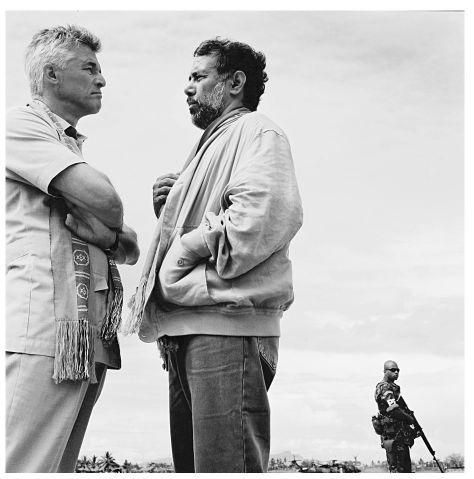

Vieira de Mello and Xanana Gusmão.

The arrival of the UN had raised expectations that, thanks to familiar UN funding strictures, the mission could not deliver. The Security Council had handed UNTAET an ambitious mandate and a generous budget of more than $600 million. But the UN rules still forbade peacekeeping funds from being spent on rebuilding Timorese electricity grids or on paying the salaries of Timorese civil servants. Just as had been true in Cambodia and Kosovo, the UN budget could be spent only on UN facilities and UN salaries

.

“Something is clearly not right if UNTAET can cost $692 million, whereas the entire budget of East Timor comes to a bit over $59 million,” Vieira de Mello declared before the Security Council. “Can it therefore come as a surprise that there is so much criticism of United Nations extravagances, while the Timorese continue to suffer?”

21

.

“Something is clearly not right if UNTAET can cost $692 million, whereas the entire budget of East Timor comes to a bit over $59 million,” Vieira de Mello declared before the Security Council. “Can it therefore come as a surprise that there is so much criticism of United Nations extravagances, while the Timorese continue to suffer?”

21

An even more remarkable UN rule held that UN assets could be used only by mission staff. This meant that, although the UN was there to assist in “state-building,” owing to liability concerns, the Timorese technically could not be transported on UN helicopters or in UN vehicles. UN staff eventually had more than five hundred vehicles, but Vieira de Mello had to break the rules in order to get a dozen of them released for the top Timorese leaders who would one day be running the country themselves.

22

“This is ridiculous,” he exclaimed during one of many arguments with the UN official in charge of administration. “I have the authority to order troops to open fire on militia leaders, but I don’t have the authority to give a computer to Xanana Gusmão!” Since New York was thirteen hours behind East Timor, he could rarely get the authorization he needed in a timely fashion. Prentice explains, “There will always be that tension, with headquarters thinking we are all a bunch of Colonel Kurtzes, and the field people thinking, ‘These guys who just sit behind their nice desks don’t understand anything.’” The rules, Vieira de Mello wrote in a “lessons learned” paper, “make the UN appear arrogant and egotistical in the eyes of those whom we are meant to help.”

23

The World Bank administered a $165 million trust fund for East Timor, which was meant to be used for vital reconstruction, but Vieira de Mello had no say on how the budget was disbursed.

24

“We are very focused on the risk of corruption. We don’t always recognize that there’s a similar risk in delay,” recalls Sarah Cliffe, who ran the World Bank program there. “Something is probably not right if we have the same rules for a $500,000 grant as we do for a $400 million loan.”

22

“This is ridiculous,” he exclaimed during one of many arguments with the UN official in charge of administration. “I have the authority to order troops to open fire on militia leaders, but I don’t have the authority to give a computer to Xanana Gusmão!” Since New York was thirteen hours behind East Timor, he could rarely get the authorization he needed in a timely fashion. Prentice explains, “There will always be that tension, with headquarters thinking we are all a bunch of Colonel Kurtzes, and the field people thinking, ‘These guys who just sit behind their nice desks don’t understand anything.’” The rules, Vieira de Mello wrote in a “lessons learned” paper, “make the UN appear arrogant and egotistical in the eyes of those whom we are meant to help.”

23

The World Bank administered a $165 million trust fund for East Timor, which was meant to be used for vital reconstruction, but Vieira de Mello had no say on how the budget was disbursed.

24

“We are very focused on the risk of corruption. We don’t always recognize that there’s a similar risk in delay,” recalls Sarah Cliffe, who ran the World Bank program there. “Something is probably not right if we have the same rules for a $500,000 grant as we do for a $400 million loan.”

In every sector there was a debate about how much to rely upon the Timorese and how much international expertise to enlist. “The natural reflex of an international organization is to dump lots of international people into a situation,” recalls Hansjörg Strohmeyer, Vieira de Mello’s legal adviser who accompanied him to East Timor as well as Kosovo. Strohmeyer instead canvassed the country for lawyers. The Australian-led force dropped leaflets from airplanes, calling for qualified Timorese to contact the UN. And the UN employed a pair of Timorese to drive around Dili on their mopeds to put out the word that lawyers would meet every Friday at 3 p.m. on the steps of the parliament building.

Within a week the UN had identified an initial group of seventeen jurists, and lacking chairs or furniture to sit on, they sat with Strohmeyer on the ground.

25

The educated Timorese generally had only bachelor’s degrees from Indonesian universities, but they had what Vieira de Mello called

“une rage de bien faire, de vite faire”

—a rage to do well, to do fast.

26

In a moving ceremony on January 7, 2000, Vieira de Mello handed black robes to eight judges and two prosecutors in the burned-out shell of the courthouse in Dili.

27

Domingos Sarmento, the former FALINTIL guerrilla fighter, was one of the hastily trained Timorese who was given a robe that day. “Mr. Sergio handed me the robe, and I felt like he was handing me the country,” he recalls. Sarmento and the other UN-appointed judges took up offices in smoke-blackened chambers in courthouses that the Indonesians had stripped of their doors, windows, and pipes.

28

25

The educated Timorese generally had only bachelor’s degrees from Indonesian universities, but they had what Vieira de Mello called

“une rage de bien faire, de vite faire”

—a rage to do well, to do fast.

26

In a moving ceremony on January 7, 2000, Vieira de Mello handed black robes to eight judges and two prosecutors in the burned-out shell of the courthouse in Dili.

27

Domingos Sarmento, the former FALINTIL guerrilla fighter, was one of the hastily trained Timorese who was given a robe that day. “Mr. Sergio handed me the robe, and I felt like he was handing me the country,” he recalls. Sarmento and the other UN-appointed judges took up offices in smoke-blackened chambers in courthouses that the Indonesians had stripped of their doors, windows, and pipes.

28

With the departure of Indonesian security forces, East Timor desperately needed to deter violent crime. The well-equipped Australian-led Multinational Force had, in January 2000, handed off to a traditional UN peacekeeping force, composed of 8,500 lightly armed blue helmets. This time, unlike in Kosovo, the force commander would report to Vieira de Mello.The UN civilian police were as slow as ever to arrive. Resolution 1272 had authorized the dispatch of some 1,600 officers, but three months into the mission only 400 UN police had turned up.

29

He tried to find a local solution by opening the country’s first police training college.The college enrolled fifty Timorese trainees, including eleven women, in a three-month crash course. But no matter how long he served in the UN system, or how many frustrated cables he wrote to New York, Vieira de Mello had made little progress in finding the means to fill the inevitable security void that followed the UN’s arrival in vulnerable places.

29

He tried to find a local solution by opening the country’s first police training college.The college enrolled fifty Timorese trainees, including eleven women, in a three-month crash course. But no matter how long he served in the UN system, or how many frustrated cables he wrote to New York, Vieira de Mello had made little progress in finding the means to fill the inevitable security void that followed the UN’s arrival in vulnerable places.

Because the prisons had been torched and all the prison guards had fled to Indonesian territory, few arrests could be accommodated, and many criminals had to be released in order to make way for new arrivals. In April 2000 Vieira de Mello said, “We cannot fill jails that we don’t have.” He suggested that community service sentences be given to “people who have not done bodily harm, who do not have blood on their hands.”

30

This meant that many lawbreakers were let loose.

30

This meant that many lawbreakers were let loose.

Other books

Experiment (Hybrid Book 2) by Emma Jaye

The Hunt Chronicles (Book 2): Revelation by Demers, J.D.

Too Many Secrets by Patricia H. Rushford

Capital Risk by Lana Grayson

Decline in Prophets by Sulari Gentill

The Seducer by Claudia Moscovici

Thin Lies (Donati Bloodlines #1) by Bethany-Kris

La puerta de las tinieblas by Massimo Pietroselli

Created By by Richard Matheson