Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World (50 page)

Read Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World Online

Authors: Samantha Power

BOOK: Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World

8.76Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

On August 30 the Timorese headed to the polls for the long-awaited vote on independence.

2

UN election observers estimated that more than half the voters were already lined up when the polls opened at 6:30 a.m.

3

Worried about Indonesia’s wrath, most went directly from the polling stations to hiding in the hills. Some 98.6 percent of registered Timorese cast ballots.

2

UN election observers estimated that more than half the voters were already lined up when the polls opened at 6:30 a.m.

3

Worried about Indonesia’s wrath, most went directly from the polling stations to hiding in the hills. Some 98.6 percent of registered Timorese cast ballots.

On September 4, 1999, anxious Timorese gathered around their television sets and radios to hear Ian Martin, the head of the UN election mission, read the results. Many wept joyously when the local radio and television reporters translated Martin’s announcement: 78.5 percent of Timorese had voted for independence. “This day will be eternally remembered as the day of national liberation,” declared Xanana Gusmão, the Timorese independence leader, who had been jailed in Indonesia since 1992. Domingos Sarmento, a former guerrilla who had also spent time in an Indonesian prison, listened to the news in his Dili home with his family. Upon hearing the results, he and his relatives went outside holding hands, and they kissed the land. “We were kissing something that finally belonged to us,” he recalls. “East Timor was a country.” But in fact the Indonesians had other plans in mind.

Within an hour of the announcement of the results, the sound of gunfire and screams abruptly halted Timorese celebrations. Black-uniformed pro-Indonesian militia, backed by the Indonesian army and police, embarked upon a savage looting, cleansing, and killing spree that left at least three-quarters of all property burned or destroyed, most of the population purged from their homes, and more than a thousand Timorese dead.

4

The actions were calculated to destroy East Timor’s prospects for survival. Indeed, the gunmen went so far as to pour battery acid into the electrical generators. “We knew the Indonesians were going to do something dramatic,” recalls Taur Matan Ruak, then commander of the Timorese guerrilla resistance. “When you kill an animal, its last movement is like a spasm, and it is very strong.” In the next fortnight, the marauding militia also butchered sixteen Timorese employed by the UN as election workers.

5

José Ramos-Horta, the longtime face of Timor’s movement for independence and corecipient of the 1996 Nobel Peace Prize, helplessly watched events unfold from New York, where he had flown to lobby the Security Council. “I saw on CNN that whole towns were being burned to a crisp, and my family in East Timor was hysterical with fear,” he recalls. “I thought that we were about to see the end of East Timor.”

4

The actions were calculated to destroy East Timor’s prospects for survival. Indeed, the gunmen went so far as to pour battery acid into the electrical generators. “We knew the Indonesians were going to do something dramatic,” recalls Taur Matan Ruak, then commander of the Timorese guerrilla resistance. “When you kill an animal, its last movement is like a spasm, and it is very strong.” In the next fortnight, the marauding militia also butchered sixteen Timorese employed by the UN as election workers.

5

José Ramos-Horta, the longtime face of Timor’s movement for independence and corecipient of the 1996 Nobel Peace Prize, helplessly watched events unfold from New York, where he had flown to lobby the Security Council. “I saw on CNN that whole towns were being burned to a crisp, and my family in East Timor was hysterical with fear,” he recalls. “I thought that we were about to see the end of East Timor.”

Fearing a human cataclysm, Gusmão instructed Timorese rebels to turn the other cheek. “If we strike back,” Matan Ruak, the guerrilla commander, told his troops, on Gusmão’s instruction, “we will give the international community the excuse they want to call this a civil war, to equate us with the Indonesian militias.We have to stay clean.”

On September 5, after an American UN policeman was shot in the stomach, Martin ordered the withdrawal of UN election staff from rural areas. Timorese and international UN workers flocked to the capital, Dili, gathering at the UN base there. They saw that many terrified Timorese with no connection to the UN had taken shelter at a high school that abutted the UN compound. As night fell, a mob of militiamen hacked one man to death in the school yard and then began firing homemade guns—welded pipes packed with nails and gunpowder that were set off with cigarette lighters—at the Timorese, who fled toward the UN compound.

UN security officers guarding the base initially fended off the desperate Timorese. But fearing that the militia were closing in on them, mothers began hurling their children over the concrete wall separating the high school from the UN complex. Other Timorese cut themselves as they forced their way through holes they had sliced into the razor wire fence. As UN staff saw parents begin to follow their children over the wall, they formed an impromptu assembly line, passing the Timorese from one pair of hands to the next, until they were safely inside the UN building. The nighttime images of panic and rescue were broadcast globally. By the end of the evening more than fifteen hundred Timorese had joined foreign journalists and UN Timorese and international staff in the UN compound, where they slept on cardboard and shared dwindling rations. Ramos-Horta’s thirty-eight-year-old sister, Aida, and her six children, aged three, five, eight, ten, thirteen, and fourteen, were among those being sheltered. With corpses lining the streets, the sound of gunfire echoing through the night, and bare-chested militiamen brandishing large machetes outside the UN gate, UN staffers feared that the mob would storm the compound.

Vieira de Mello watched events unfold from New York, and still undersecretary-general for humanitarian affairs, he attempted to coordinate the UN’s humanitarian response. He herded the heads of the World Food Program, UNHCR, and the major aid groups together to ramp up their emergency aid deliveries. But while the militia were on the loose, he knew it would be very difficult to reach those in greatest need. He believed the crisis was so severe that military intervention, that rare and risky measure, was necessary.

Although the evidence indicated that Indonesian armed forces were committing and abetting the massacres, Western diplomats continued to point to the original referendum agreement in which Indonesia had accepted responsibility for maintaining East Timor’s security. When Sandy Berger, the national security adviser to President Clinton, was asked why the United States had not stepped up to try to stop the violence, Berger said,“You know, my daughter has a very messy apartment up in college; maybe I shouldn’t intervene to have that cleaned up. I don’t think anybody ever articulated a doctrine which said we ought to intervene wherever there’s a humanitarian problem.”

6

None of the major powers seemed inclined to rescue the Timorese. “Nobody is going to fight their way in,” said Robin Cook, the British foreign secretary.

7

6

None of the major powers seemed inclined to rescue the Timorese. “Nobody is going to fight their way in,” said Robin Cook, the British foreign secretary.

7

But because it was UN staff who had staged the referendum, it was again the organization rather than the specific countries that constituted it that came under fire.The French newspaper

L’Express

ran a commentary by philosopher André Glucksmann, who called for the abolition of the UN, the “alibi of cynical powers”:

L’Express

ran a commentary by philosopher André Glucksmann, who called for the abolition of the UN, the “alibi of cynical powers”:

The UN lured the Timorese into an ambush: it offers them a free referendum, they vote under its guarantee, it delivers them to the militias’ knives . . . Is the ability to foresee and to reform inversely proportional to the size of its resources? 180 nations, a lot of money, a plethora of bureaucrats. . . . A warning to the brave people who are counting on it: the UN knows, the UN keeps quiet, the UN withdraws.

8

8

Le Point,

another French newspaper, published an editorial by the prominent philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy, who invoked Somalia, Rwanda, and Srebrenica as the “other theaters of the UN’s shame.” He slammed the “slow but sure League-of-Nations-ization of the UN.”And he closed the appeal by arguing, “The UN did its time. The time of the UN has passed. We have to finish off this macabre farce which the UN has become.”

9

another French newspaper, published an editorial by the prominent philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy, who invoked Somalia, Rwanda, and Srebrenica as the “other theaters of the UN’s shame.” He slammed the “slow but sure League-of-Nations-ization of the UN.”And he closed the appeal by arguing, “The UN did its time. The time of the UN has passed. We have to finish off this macabre farce which the UN has become.”

9

Vieira de Mello was so incensed by the attacks that he fired off an intemperate response, which

Le Monde

entitled “Retort to Two Intellectual Show-offs.” The under-secretary-general denounced the “two prosecutor-philosophers.” Although it was “so easy to caricature, to ridicule, to defame” the UN “from the comfort of their Parisian homes,” he wrote, their reasoning was an “insult to philosophy” and would do nothing to improve people’s lives. He defended the UN referendum, which he noted had the full support of the Timorese. And he wondered why he could not recall Glucksmann and Lévy denouncing Indonesia’s occupation of East Timor.

10

Instead of “shooting us in the back” by urging that the UN “rampart against anarchy” be destroyed—“a nonsense philosophically, politically and practically”—Vieira de Mello wrote, the men could do some real good by pressing Western governments to rescue East Timor.

11

Le Monde

entitled “Retort to Two Intellectual Show-offs.” The under-secretary-general denounced the “two prosecutor-philosophers.” Although it was “so easy to caricature, to ridicule, to defame” the UN “from the comfort of their Parisian homes,” he wrote, their reasoning was an “insult to philosophy” and would do nothing to improve people’s lives. He defended the UN referendum, which he noted had the full support of the Timorese. And he wondered why he could not recall Glucksmann and Lévy denouncing Indonesia’s occupation of East Timor.

10

Instead of “shooting us in the back” by urging that the UN “rampart against anarchy” be destroyed—“a nonsense philosophically, politically and practically”—Vieira de Mello wrote, the men could do some real good by pressing Western governments to rescue East Timor.

11

Secretary-General Annan too was defensive, as the associations with Rwanda and Srebrenica were inescapable. He claimed that the Indonesian slaughter was unexpected: “If any of us had an inkling that it was going to be this chaotic, I don’t think anyone would have gone forward. We are no fools.”

12

When journalists challenged him to account for why the UN had not deployed force to stop the atrocities, he explained that he did not have a protection force of his own. The countries that composed the UN were to blame.“We all talk of the United Nations and the international community,” Annan said. “The international community is governments—governments with the capacity and the will to act. The governments have made it clear that it will be too dangerous to go in.”

13

When a reporter asked if he was advocating a Kosovo-style intervention, he avoided making a forceful appeal, instead answering with characteristic tentativeness: “I do not think your analogy is completely irrelevant.”

14

12

When journalists challenged him to account for why the UN had not deployed force to stop the atrocities, he explained that he did not have a protection force of his own. The countries that composed the UN were to blame.“We all talk of the United Nations and the international community,” Annan said. “The international community is governments—governments with the capacity and the will to act. The governments have made it clear that it will be too dangerous to go in.”

13

When a reporter asked if he was advocating a Kosovo-style intervention, he avoided making a forceful appeal, instead answering with characteristic tentativeness: “I do not think your analogy is completely irrelevant.”

14

An unshaven and frazzled Ramos-Horta shuttled between New York and Washington, invoking Rwanda whenever he could. “It was clear that people in the office of the secretary-general and in the White House were traumatized by Rwanda,” he recalls. “So I kept repeating, ‘Do you want another Rwanda in Timor? That’s what you’re going to get if you don’t act now.’ ” Vieira de Mello, who spoke often about the Don Bosco school in Rwanda

that the Belgians had abandoned, had the same concern. The Security Council had instructed UN election workers to carry out the referendum. Surely, he thought, the countries on the Council would not again abandon civilians who had trusted them.

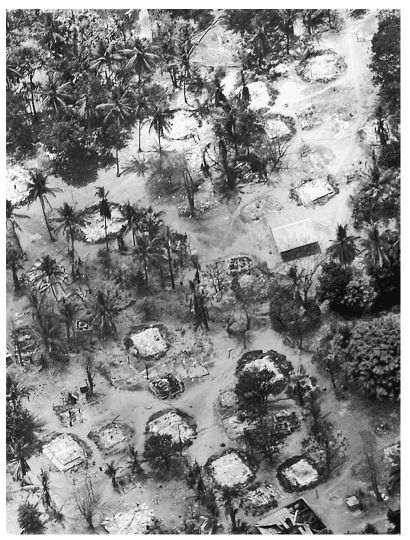

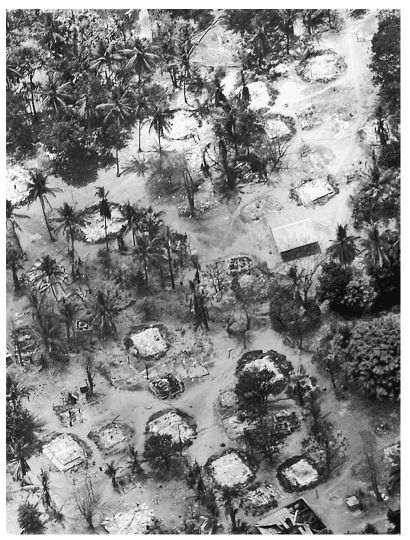

The remains of East Timorese homes in the Ermera district, thirty-one miles south of Dili, September 27, 1999.

When the violence began, the BBC chartered a plane to evacuate journalists, but a few remained and used UN satellite phones to plead for outside help. The pressure on Annan and the countries within the UN mounted. A vast network of religious groups and other grassroots organizations kicked into gear, demanding intervention. On September 7, Annan was informed that the UN had received 60,000 e-mails regarding East Timor, a deluge of concern so great that a separate computer server had to be set up to handle the influx.

15

15

Martin was worried both about the bloodshed in the country and about the people gathered at the compound. In a reversal of its previous position, Australia agreed to admit Timorese UN staff on the condition that Australian citizens be evacuated from East Timor first and that any Timorese who landed in Darwin, Australia, would not be eligible to apply for longer-term visas.

16

16

Martin’s bigger problem was the fifteen hundred Timorese civilians with no UN connection who had poured into the compound on September 5 and whom Australia would not take. The militiamen who prowled outside the blue-painted gates seemed poised to attack at any point. Piled into a large auditorium, the displaced Timorese sang songs that the UN had made up for the election, lit candles, and prayed before their small crucifixes and statues of the Virgin Mary.

17

One Timorese woman gave birth to a baby boy inside the compound, and out of gratitude to the UN mission in East Timor, or UNAMET, the woman chose an unusual name for her new son: “Pedro UNAMET.”

18

17

One Timorese woman gave birth to a baby boy inside the compound, and out of gratitude to the UN mission in East Timor, or UNAMET, the woman chose an unusual name for her new son: “Pedro UNAMET.”

18

The UN had a policy of never evacuating civilians, but Martin urged New York to lobby member states to do something to protect all Timorese (UN and non-UN alike) at the compound. Hearing nothing, on the evening of September 8, Martin felt he had no choice but to follow the advice of Alan Mills, the head of UN civilian police, and his security advisers, and recommend to New York that the secretary-general declare a “Phase V” emergency.

22

Annan reluctantly accepted the recommendation and ordered the withdrawal of all UN staff. Before Martin had shared the news with UN officials at the compound, most learned of the evacuation from CNN.

22

Annan reluctantly accepted the recommendation and ordered the withdrawal of all UN staff. Before Martin had shared the news with UN officials at the compound, most learned of the evacuation from CNN.

Other books

Now I Know More by Lewis, Dan

Power Games by Victoria Fox

Daughter of Chaos by McConnel, Jen

The Golden Shield of IBF by Jerry Ahern, Sharon Ahern

The Killing Sea by Richard Lewis

The First Detect-Eve by Robert T. Jeschonek

Harriet Hume: A London Fantasy by Rebecca West

The Bees: A Novel by Laline Paull

Wicked Plants by Amy Stewart

The Death of Nnanji by Dave Duncan