Catherine Price (3 page)

Authors: 101 Places Not to See Before You Die

I

n the realm of teenage male fantasies, taking a bath in beer is right up there with doing body shots off Megan Fox. But for people who would rather drink their hops than bathe in them, the idea is less sexy than sticky.

If you fall into the latter camp, skip the Chodovar brewery in the Czech Republic. Billed as “Your beer wellness land,” it offers hops-crazed visitors the chance to soak their cares away in bathtubs full of their favorite beverage. Complete with warm mineral water and a “distinct beer foam of a caramel color,” the brewery’s special dark bathing beer contains active beer yeast, hops, and a mixture of crushed herbs. But the fun doesn’t end with the bath: afterward, guests are led to a relaxation area where they are wrapped in a blanket in a dim room with pleasant music and given one of several complimentary drinks.

“The procedures have curative effects on the complexion and hair, relieve muscle tension, warm up joints, and support immune system of the organism,” says Dr. Roman Vokaty, the spa’s official balneologist, in response to the obvious question of why a beer bath is a good idea. One could argue that the combination of a post-bath massage and the bottles of Chodovar’s lager consumed

while

the organism soaks in the tub might have just as much, if not more, of an impact on the organism’s well-being than the beer’s carbon dioxide and ale yeasts. But then, I’m not a balneologist.

If you like the idea of wasting a perfectly good drink, check out some of Europe’s other beer spas: Starkenberg in Austria, for example, has been known to fill an entire swimming pool with Pilsner, and the Landhotel Moorhof in Franking, Austria, offers a brewski facial made from ground hops, malt, honey, and cream cheese. According to one survivor, it “smells remarkably like breakfast.”

J

une 16, 1991, was Father’s Day. It was also the day I got my period for the first time, and it occurred right in the middle of a family vacation to China—a three-week self-guided journey with my parents and my mom’s seventy-year-old friend, Betty.

I was mortified. To make things worse, the hotel we were in didn’t have sanitary supplies, and in China at the time it was difficult to find a store opened to foreigners at all, let alone one with Western toiletries. Had we been in America, the next step would have been for us to go to a drugstore together where I, too embarrassed to pick out sanitary products myself, would inspect the toothbrush display as my mother yelled questions from the next row over like “Scented or non-scented?” and “Do you want wings?” Instead, my mother convinced me to allow her to tell Betty; the two conferred in hushed tones, and when back in my room, Betty rummaged through her toiletry bag and presented me with a Depends.

Wearing an adult diaper as a twelve-year-old added insult to the injury of menstruation, and our itinerary only made things worse. Presumably if we’d been sticking around at our hotel, we would have been able to find maxi-pads somewhere in the city before Betty’s supplies ran out. However, my parents, eager for an authentic, self-guided China experience, had arranged for us to get on a train to a city twenty-three hours away. No sooner had we left for the station than my body, unsatisfied with the humor of me simply menstruating on a Chinese train, broke out in hives. My mother gave me two extra-strength Benadryl. I stumbled to the train platform with my parents and woke up three hours later on an upper bunk in a moving train, in a car with vomit stains on the carpet and circles at the end of each bed where people’s heads had wiped away the dirt. My parents and Betty were giggling on the bunks below me as they played bridge and drank “tea” they’d brewed from water and Johnny Walker Black. I needed to use the bathroom.

I slid off the top bunk and unlatched the door to our cabin to find the toilet, but my mother stopped me before I could leave.

“It’s clogged,” she said. “Betty and I tried to use it, and it smells so bad, we almost threw up.”

“What am I supposed to do?”

“Do what we did,” said my mother, which was greeted by tipsy laughter from Betty and my father. “Pee in this.”

My mother then handed me a Ziploc bag.

What bothered me about this was not so much the fact that my mother was telling me to urinate into a freezer bag, but rather, how I could do so with my father in the room. Holding the empty bag, I glared at my mother, glanced at my father, and then glared at her again until she realized what I was trying to communicate.

“Richard, go out in the hall. Catherine needs some privacy.”

With my mother and Betty playing cards in front of me, I squatted down, pulled down my pants, pushed aside my diaper, and peed into the bag, trying my best to keep my balance on my heels as the train rocked back and forth.

“I don’t want it,” my mother said when I tried to hand it to her. “Give it to your father.” I slid the door open and found him standing in the hallway watching rice paddies out the window. A childhood polyps operation gone awry left him with no sense of smell, so he took the bag when I offered it and carried it down the hall to the bathroom. He stuffed the bag down the toilet with a hanger, it burst upon the tracks, and he returned to our cabin to finish his tea.

When we arrived at our hotel in Beijing the next day, my family’s first destination was the Summer Palace. My first destination was the bathroom, a squat building a short, urine-scented walk away from the park entrance. Inside, a long row of waist-high, doorless stalls subdivided a porcelain trough pitched slightly toward one end of the room, over which women squatted on their heels, bottoms bared to the world. Some read magazines; most held tissues clamped to their noses to keep out the stench. Driven by the pressure of my bladder and the presence of my Depends, I ignored the smell and forged ahead toward the end of the room, picking the last stall so that I would be exposed to the fewest number of people possible. I glanced around to see if anyone was watching and yanked my pants to my knees, realizing only when I looked down that my stall was downstream from the other seven.

The second thing I noticed was that my period had stopped—apparently it had decided that two and a half days was sufficient for a first-time visit. This filled me with joy until I realized that, now that I had begun to ovulate, it would return once a month for the rest of my child-bearing years. When I looked up to the ceiling in a “Why, God?” moment, my eyes were stopped halfway by a third realization: despite my attempts at seclusion, the other women in the room had seen me enter. Curious about what a Caucasian twelve-year-old would look like while urinating, several had walked up to where I was squatting and were standing next to my stall, giggling behind their tissues as they stared at my naked backside. I felt self-conscious enough simply being an American in China, but being watched in a bathroom while wearing a diaper was as embarrassing as going bra shopping with my father. I pulled my pants up and they scattered back to their places in line as I pushed past them, ashamed. If this was what it meant to be a woman, I wanted to go home.

Postscript: I returned to China in the summer of 2002 and am happy to report that train travel has remarkably improved. Unfortunately, however, my bottom is still considered a tourist attraction—when my friend and I visited a public squat toilet, we looked up to find a group of women taking photographs.

I

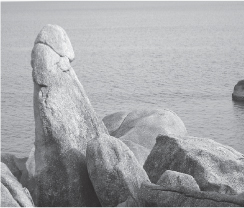

f I suggested that you visit the Grandpa and Grandma Rocks on Thailand’s Lamai Beach, what would you expect to see? The silhouettes of two aged lovers? A piece of granite resembling wrinkled hands intertwined? No and no. Grandma and Grandpa are rock formations that look like genitalia.

When I first heard about these rocks—referred to locally as Hin Ta and Hin Yai—I thought that seeing genitalia in the rocks might require effort, like how it takes a certain degree of creativity to find Jesus in your toast. But these grandparents aren’t subtle. Granddad is clearly a large, erect penis. And Grandma has spread her legs open to the sea, positioned so that she’s caressed by every wave that hits the shore.

When you see the rocks, you will probably wonder whether people in Thailand have a very different relationship with their grandparents from what we have in America. Perhaps, but in this particular case, the nickname comes from a legend—Ta Kreng and Yai Riem, an elderly couple, were on their way to try to procure a bride for their grandson from a family to the north when their boat got caught in a storm. They drowned. And then, as so often befalls seafaring grandparents, they were turned into rocks representing their respective naughty bits.

These days, it’s probably best not to bother visiting unless you enjoy fighting your way through street vendors selling phallic souvenir T-shirts just so that you get a picture of yourself perched on Grandma’s thigh. The beach isn’t particularly good for swimming, and you’ll be surrounded by people who decided that, of the many attractions Thailand has to offer, all they really wanted to see was a granite penis.

Grandpa

Benjamin Thomas

Grandma

Sigrid Georgescu and Alex Falls

S

ome people might argue that San Jose, California, is itself a place not worth visiting before you die. Fair enough. But if you do find yourself driving its wide, traffic-clogged streets, you may be tempted to stop at the Winchester Mystery House. It’s impossible to drive in or out of San Jose without coming across a billboard advertising the bizarre 160-room mansion built by Sarah Winchester, heiress to the fortune of the Winchester Repeating Arms Company.

But please, resist the urge.

The story of the Winchester Mystery House—or, rather, the legend—is as follows: after her infant daughter and husband passed away, Sarah Winchester visited a psychic who told her that her loved ones’ deaths were caused by the souls of the people who had been killed by the Winchester repeating rifle (tagline: “The Gun That Won the West”). If she didn’t take drastic action, said the psychic, Sarah Winchester could be next. The psychic supposedly told her that the only way to appease the angry spirits was to go west and build a house—not too difficult a task for a woman who had an income of about $1,000 a day in the late 1800s. But there was one catch: the house could never be completed. If construction ever stopped, the spirits would seek their revenge once more.

And so Sarah Winchester moved from Connecticut to San Jose, bought an unfinished eight-room farmhouse, and started construction. She hired shifts of men to work around the clock, seven days a week, 365 days a year. From the day she began until her death thirty-eight years later, the workers never stopped. Every evening, legend has it, Sarah Winchester would retreat to a special séance room in the middle of the house to commune with lost souls and, while she was at it, figure out the next day’s construction plans.

The result is a sprawling mansion that gives a sense of what happens when a multimillion-dollar fortune and a belief in the paranormal are combined in a woman with no architectural training. There are stairs that lead to the ceiling, chimneys that stop a foot and a half short of the roof, cabinets that are actually passageways, and a second-story “door to nowhere” that opens fifteen feet above the ground outside. Throughout the house are touches of grandeur—hand-inlayed floors, Tiffany glass windows—and bizarre architectural elements, like custom-designed window panes in the shape of spider webs and a preoccupation with the number thirteen.

The house has been open to the public, in one form or another, since soon after Winchester’s death in 1922. But unfortunately for anyone intrigued by her story, its legend is more interesting than the tour itself. Part of the problem is that Winchester left all of her furniture, household goods, pictures, and other artifacts to her niece, the alliterative Mrs. Marian Merriman Marriott, who wasted no time in clearing out the house and selling them off. This was no doubt profitable for Mrs. M, but it means that aside from a few rooms that have been refurnished with period-appropriate decor, the gigantic house is empty. What’s more, despite the legend of the house—the séances, the spirits, the psychic—no one really knows for certain

why

Sarah Winchester built her house the way she did. Maybe the story is true; maybe she was just participating in an early-twentieth-century version of

Extreme Home Makeover

. Or maybe she was just bat-shit crazy.

Regardless, like all good tourist traps, the opportunities to spend money at the Winchester House don’t end with the tour. In addition to an arcade offering 1980s video games, there’s an antique products museum featuring Winchester flashlights, Winchester roller skates, and Winchester wrenches, and a display titled

WINCHESTER HOUSE IMMORTALIZED IN GINGERBREAD.

The nearby gift shop is a warehouse-size collection of Winchester House shot glasses, tote bags, T-shirts, and specialty wine, all sharing shelf space with butterfly-shaped wind chimes, novelty dishtowels, and magnets announcing that

“STRESSED” IS “DESSERTS” SPELLED BACKWARDS.

The effect of all this—the gift shop, the mile-long tour through endless empty rooms, the near total lack of concrete facts—is to leave you feeling as if you’d just binged on McDonald’s: full, and yet, surprisingly empty. In fact, the only justification for the house’s popularity as a tourist attraction is its size—whereas usually one would balk at the prospect of paying $26 to tour a crazy lady’s empty home ($5 more if you want to see the plumbing system), the Winchester House is so large that with some creative math, it’s almost justifiable: each of its 110 rooms costs less than 25 cents to see.

But still, one question remains: who signs up for the annual pass?

Nota bene: The Winchester Mystery House is not to be confused with the pirate-themed haunted house that opens in Fremont, California, every Halloween. That is totally different—though, incidentally, also not worth seeing.