Catherine Price (10 page)

Authors: 101 Places Not to See Before You Die

A

lso known as the Eastern Garbage Patch or the Pacific Trash Vortex, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is a huge, swirling mass of plastic in the middle of the ocean that’s been estimated to be twice the size of Texas.

The garbage patch—if one hundred million tons of debris can be called a patch—was discovered in 1997 by a Californian sailor, oceanographer, and furniture restorer named Charles Moore, who decided to take a shortcut on his way back from a sailing competition in Hawaii. He and his crew sailed their fifty-foot catamaran through the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre—an area usually avoided by sailors because of its lack of wind—and were shocked to find themselves navigating through what appeared to be an endless sea of plastic.

Bottle caps, Legos, flip-flops, toothbrushes, Styrofoam cups, footballs, even entire kayaks—Moore had accidentally guided his boat into the final resting place for an incomprehensible amount of plastic trash, pieces of which were close to half a century old. Intrigued and horrified, Moore returned on a research trip two years later and discovered that the patch extended some thirty feet underwater, with increasingly tiny pieces of plastic swirling in the ocean like multicolored fish food. (Since no microbes exist that can digest plastic, it doesn’t biodegrade; instead, exposure to sunlight and currents breaks its polymer chains into smaller and smaller pieces.) In parts, the water of the patch contained six times more plastic than it did plankton—a ratio that has since dramatically increased.

Moore brought himself out of retirement to found the Algalita Marine Research Foundation, which is devoted to studying the composition and effects of this giant mass of plastic. This isn’t the cheeriest research assignment; Algalita’s research assignments include examining the stomach contents of dead albatrosses (the United Nations Environment Programme estimates that plastic debris kills more than a million seabirds a year) and investigating how, exactly, the toxicants in plastic dissolve into ocean water. Among the disturbing facts they’ve discovered: a lot of the plastic trash is from nurdles—

lentil-size pellets of raw plastic that are used in manufacturing and frequently escape into the water. Also, plastic has an unfortunate tendency to act as a chemical sponge for other toxicants, like hydrocarbons and DDT, which nurdle-nibbling fish can pass up the food chain to our dinner plates.

So why not just clean it up? According to the folks at Algalita, that would be completely impossible: not only is the patch miles wide and at least 30 feet deep, but it’s less a plastic island than a plastic soup, full of tiny particles that can’t be recovered without scooping up plankton and other marine life at the same time. Even worse, since much of the plastic is so tiny and/or transparent that it doesn’t show up in satellite images, no one yet knows how much of the world’s oceans have been contaminated.

REBECCA SOLNIT

The Customs Office at the Buenos Aires Airport

I

t would not be quite true to say that the package containing my all-weather jacket for Tierra del Fuego arrived safely in Buenos Aires. Rather, in this country that suggests all was not lost when the Soviet Union dissolved, I—with visions of packages dancing in my head—got to my mailing address only to find a sheaf of stapled papers with, on top, a long letter addressed to

estimado cliente

. “Esteemed client,” it said, “call these number between 10 and 3 or these numbers from 9 to 1 and 2 to 5, and then . . .”

So I called my excellent cousin Bernardo, a native of Buenos Aires, who later told me that when his wife heard I had to deal with customs, she said something akin to “oh my God,” or “the Lord preserve us,” or some such locution. We drove across town from Bernardo’s business at about 2

P.M.

via the lawless, jammed-up surface streets—there are very few stop signs and not so many lanes or traffic lights in the Darwinist traffic here—and then the long straightaway with the innumerable tolls of about 17 cents apiece to the international airport. Bernardo asked a few dozen people to initiate us into the secret of the location, and we stashed the car in a nonsecured parking lot and asked some more people for directions, some of whom also needed to look at my passport, and so we arrived at the secret customs hell.

Bernardo talked en route about the endless corruption of this country’s government, from the airline that was supposed to be de-privatized and turned out to be run by part of the president’s family, which was shipping suitcases of cocaine on passenger-less passenger planes to Spain, to the congressional aide who suggested that, for a sum of money, the law affecting his business could be rearranged. So, to customs: a corridor in a warehouse looking into three air-conditioned cubicle-like offices. We went into the first cubicle and got some papers stamped so we could stand in the line of anxious, frustrated people for an hour or so in the extraordinary heat, not knowing if our turn would ever come before the office shut in a mere two and a half hours.

Waiting, waiting, waiting, and then finally the appointment in office two, with the young woman with badly dyed hair and forms that must be filled out, but whose government copies would only be tossed in a loose pile, suggesting no one would ever look at them again or even be able to find anything in them (in this country that still uses carbon paper). And then to office three, where we got some more papers and rubber stamps, showed my passport some more, and then, as though it were all an elaborate dance, a few more rotations: the melancholic official walked us to the actual parcel site where we jointly viewed my parcel’s contents to prove they were not new or valuable, and it was then sealed up again against theft by the officials with tape that was the equivalent of official seals so we could go back to office two to get another round of stamps and then back to office one to pay a toll of 43.5 pesos, about $14, and then, with the man from office three, we walked back to office four and actually received the damn thing. I thought of the funky technology and endless bureaucracy in the movie

Brazil

, the labyrinths people get stuck in, the rumpled piles of documents, and the guerrilla repairman who cuts through bureaucratic red tape to make things actually work. It was clear that though the normative purpose of data collection is data retrieval or the ability to track, these three offices with their loose piles of documents have nothing to do with any such thing. And that without a skilled local, I would’ve never seen my Tierra del Fuego gear again.

REBECCA SOLNIT

is the author of

A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster.

T

here are many contenders for the world’s least pleasant hotels—dasparkhotel in Austria puts guests up in drainpipes, for example, and the Null Stern Hotel (German for “zero star”) offers rooms in a Swiss nuclear bomb shelter. But Karostas Cietums in Latvia tops the list. A Soviet-era military prison, it was in active use till 1997, and boasts that ever since the first years of its existence, “it has been a place to break people’s lives and suppress their free will.” Sign me up for the honeymoon suite.

The prison’s original clientele was a diverse group of convicts, ranging from members of the tsarist army and deserters of the German Wehrmacht to men judged by Stalin’s government to be enemies of the people. These days, it caters to guests who are attracted to the idea of spending the night in a place where, according to the hotel’s promotional material, more than 150 people have been shot.

Unsurprisingly, accommodations are sparse; rates include iron beds and authentic prison meals, and lucky children can spend a night in prison bunks. But threadbare mattresses are far from the only attractions: in the museum, you’ll have an opportunity to try on a gas mask or buy vintage souvenirs, like former inmates’ aluminum spoons. Other options include participating in an ominous-sounding “surprise tour” and an evening activity that gives guests the chance to “live the part of a prisoner on a dismal night.” Most activities require participants to apply in advance and sign what’s referred to as “the Agreement,” which states, among other things, that “Participants may receive insulting instructions and orders which must be carried out without objection” and that “In case of disobedience prisoners may be punished.”

T

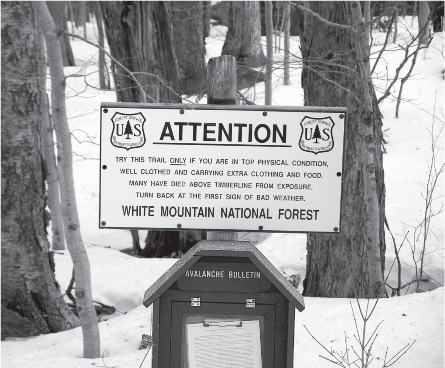

he warnings on the trails up Mount Washington don’t mince words.

STOP

they say.

THE AREA AHEAD HAS THE WORST WEATHER IN AMERICA. MANY HAVE DIED THERE FROM EXPOSURE, EVEN IN THE SUMMER. TURN BACK NOW IF THE WEATHER IS BAD.

It’s hard to objectively define worst weather, but by most people’s standards, the top of Mount Washington would qualify. At 6,288 feet, the New Hampshire mountain is small in comparison to the United States’ western peaks, but its location at the convergence of several storm tracks, not to mention its height and north-south orientation, means that it gets hit with hurricane-force winds and snowstorms all year round. Not only does Mount Washington’s summit hold the record for the world’s strongest recorded wind speed—231 miles per hour—but its average yearly temperature is only 27.2 degrees.

Despite its weather conditions, Mount Washington draws a steady stream of tourists—most of whom define conquering the summit as buying a bumper sticker that says

THIS CAR CLIMBED MT. WASHINGTON.

But hard-core hikers also tackle the mountain by foot, and occasionally they never make it down—more than one hundred people have perished on its slopes.

If you’re unfortunate enough to find yourself on Mount Washington during a winter storm and can’t find shelter, you’re probably going to die. But at least you’ll have something pretty to look at: rime ice, a feathery frosting that’s beloved by nature photographers. When a storm hits, these delicate ice structures will begin to build up on rocks, trees, and, if you wait long enough, your body. Your hands may be too numb to reach for your camera, but at least you can take comfort in knowing that your last vision will be one of which Ansel Adams would have approved.

Greg Neault/Wikipedia Commons

E

veryone knows about the U.S.-Soviet Space Race of the 1960s. But few people are aware that at the same time the two countries were vying to hurl manned spacecraft into orbit, they were also sprinting in the opposite direction: toward the earth’s core.

Or, to be more specific, toward something called the Mohorovicˇi´c Discontinuity, thought to be the boundary between the earth’s crust and its magma-filled mantle. America was the first to try—in 1957 it launched Project Mohole, a later-abandoned plan to reach the so-called Moho by drilling through the ocean floor. Distracted by a different, equally important project—launching the first dog into orbit—the Soviets didn’t get started on their own Project Moho till 1962, and started drilling in 1970. But while they may have lost that first battle, the Soviets won the war: at more than seven miles deep, the Kola Superdeep Borehole is the deepest hole in the world.

Why were the two countries racing toward this particular goal? At first, the answer seemed to be: why not? I mean, dude. It’s the world’s

deepest hole

.

But there were also scientific reasons, and as the Soviet team drilled (and drilled and drilled), taking core samples along the way, its members discovered everything from unexpected water to fossils some four miles underground. They also disproved their own assumptions about how quickly things heat up: by the time they reached their stopping point, the rock was so hot that it was malleable, flowing closed whenever the scientists replaced the drill bit. In order to continue, the project would have required new heat-resistant technology and massive renovations to its equipment.

Unfortunately, official interest in the hole had waned in the twenty-four years since the project began. And so, much to the chagrin of workers who had spent two decades in a remote outpost boring a hole into rock, drilling stopped in 1994, just 1.7 miles short of the goal.

These days the hole’s core samples—the last of which was estimated to be over 2.7 billion years old—are housed about six miles south of the drilling site. But to people not acquainted with the works of Russia’s State Scientific Enterprise on Superdeep Drilling and Complex Investigations in the Earth’s Interior, the hole is basically unknown. Which, when it comes to would-be visitors, might be a good thing—the Kola Superdeep Borehole is only about nine inches wide.