Catherine Price (12 page)

Authors: 101 Places Not to See Before You Die

Y

ou’re in Argentina, standing in what looks like an ancient town square. Around you are donkeys, sheep, and several dozen identical bearded men engaging in a variety of unpleasant activities. One is being beaten. Another is touching a leper. Another bears an enormous cross. You reach out to touch one, but he doesn’t respond. His skin is cold and hard. At that moment, a six-story Jesus rises out of a fake mountain. He turns his hands toward the sky just as a low-flying 747 threatens to clip off the top of his head. The palm trees begin to emit Handel’s

Messiah

. In the background, you hear the disembodied screams of children.

No, it’s not a bad dream. It’s Tierra Santa in Buenos Aires, one of the world’s most popular theme parks devoted to the Holy Land. Located next to a family-friendly water park and a major airport, it boasts one of the only crucifixes to be backed by a waterslide.

Since the park was designed by a renowned plastic artist, the majority of its animals aren’t alive. Neither are the palm trees, the beggars, or, for that matter, the whores. (The belly dancers are a different story.) This abundance of plastic will become especially noticeable when you are ushered into the park’s first exhibit, El Pesebre, in which robotic plastic figurines act out the nativity in what’s billed as “the world’s largest manger.” Occasionally technical difficulties delay Jesus’s birth, but since Mary goes into labor approximately once every half hour, it’s never long before the next performance.

After welcoming the son of God into the world, you’ll be set free to explore the rest of the park. A good first stop would be Creation—a laser show, religious lesson, and zoo exhibit rolled into one. In the beginning there is darkness, but it’s soon broken by a green light that bursts through a pinhole, dancing and shimmering as a deep, Godly voice booms in Spanish. Thunder crashes, dry land is formed, and before you know what day it is, the world’s first animals appear, rolling in on jerky wooden platforms with a sense of gravitas reminiscent of a high school play. A giraffe, an elephant, an animatronic gorilla. The show ends with the creation of Adam and Eve.

The park’s food stands offer biblical favorites like empanadas and chicken shawarma, but if you’re hoping for a last supper, you’ll have to settle for a plastic reenactment—it’s one of the park’s thirty-seven exhibits dedicated to important events in the Bible. (Some of the titles— Veronica Washes Jesus’s Face, Jesus Falls for a Third Time—make you wonder if they shouldn’t have quit while they were ahead.) The park also includes a small temple, mosque, and, for reasons that are not entirely clear, an exhibit about Mahatma Gandhi.

The Resurrection

Roberto Ettore/Wikipedia Commons

But Tierra Santa’s pièce de résistance is, of course, the resurrection—an attraction that, depending on your religious beliefs, can be breathtaking, sacrilegious, or just plain weird. Once every hour, park employees begin staring and pointing at the top of Crucifixion Mountain. As a crowd of onlookers focuses their cameras, a fifty-nine-foot-tall plastic Jesus rises up toward heaven, arms outstretched in a

T

. Slowly rotating, he blinks and turns his palms skyward as speakers hidden in fake palm trees blast the “Hallelujah” chorus, its triumphant melody broken only by the roar of passing planes.

H

ere’s a bit of cocktail trivia for you: a vomitorium is not actually a room where ancient Romans went to barf.

I know. You don’t want to believe me—thanks to a misunderstanding popularized in many sixth-grade history classes, most people assume that a vomitorium is a room where Romans threw up after particularly heavy meals. This would seem to be a natural extension of other weird things the Romans did, like wear togas and speak Latin. But it’s less strange to use an inflected language than it is to build a vomit room in your house. The Romans were no strangers to gluttony, but they didn’t designate specific chambers to capture the results.

Instead, a vomitorium is an architectural term for a passageway in a theater that opens into a tier of seats. Think of the entrances in a typical sports stadium—you know, the tunnels that pop you out into the stands? Those are vomitoria. The name does share its root with

vomit

—both words come from the Latin verb

vomere

(to throw up, spew). And, depending on the event, they may very well contain nauseated fans. But the name

vomitorium

itself refers to the passages’ ability to quickly move spectators into the stadium. Or, more graphically, to puke them out when the show is over.

A

bout eighty miles southwest of Cairo, Medinat al-Fayoum was once a holiday destination for thirteenth-century pharaohs; today’s highlights include lesser-known pyramids and water wheels built by ancient Greek settlers. Since Medinat al-Fayoum attracts far fewer visitors than Cairo, it offers a welcome relief from busloads of camera-toting tourists at some of Egypt’s major attractions.

However, it’s also an easy place to get paranoid. After a horrific incident in 1997 where terrorists slaughtered sixty-three tourists at an archaeological site in Luxor, a city farther south, the leaders of Medinat al-Fayoum committed themselves to making sure nothing like that ever happened in their town. So whenever Western visitors come to the city, they’re assigned their own security detail.

The problem is that no one tells you this. One traveler reported that after receiving a series of unexplained phone calls in his hotel room asking for the details of his itinerary, he and his girlfriend were stopped by a policeman on the street after dinner and told it was time to go to sleep. Once back at the hotel, they received another anonymous phone call instructing them where and when to have breakfast, and telling them that as soon as they visited the site, they’d be leaving town. Confused and scared, they spent the morning before their departure touring historical ruins with several men carrying assault rifles.

Once you realize that you’re not being abducted, having a police escort can be a fun novelty—parading down the streets with your own bodyguards is a great way to pretend that you’re important. But after a while, the Big Brother routine can get tiring, especially because most guards seem not to like their jobs. Instead of introducing themselves or acting as guides, they lurk in the background just close enough for you to know they’re there. This is particularly awkward at mealtimes, when you and your traveling companion try to enjoy your food with a guard glaring at you from the next table.

If you’re feeling naughty, you can try to evade your security detail—when’s the last time these guys played a good game of cat and mouse? But considering that they’re armed and cranky, it’s probably best to just do what they say.

T

he Russian & Turkish Baths have been open in New York’s East Village since 1892, and they’re the real deal: a sauna, an ice-cold pool, Russian and Turkish steam rooms, and a cafeteria serving borscht and Polish sausage. After locking up your belongings and trading your clothing for a threadbare towel and sandals, you’ll be set free to pick your preferred location to

schvitz

it out with a random assortment of old Russians, young hipsters, and everyone in between. If you’ve ever wondered what could be less pleasant than being smushed together with strangers in a crowded subway car in July, consider this: the baths are hotter, wetter, and on single-sex days, no one’s wearing clothes.

The most interesting room in the baths is the Russian sauna, one of the only ones in the United States. For people with heart problems, it’s also the most dangerous. Literally an oven, it’s filled with twenty thousand pounds of rock that are heated overnight and left to cool during the day. They retain enough heat to keep the room nearly unbearable for hours after the oven is turned off. That explains the white plastic buckets and the spigots of ice-cold water—the custom is to sit in the room until the heat becomes excruciating, fill up an entire bucket of ice water, and then dump it over your head. Fans of the baths call the resulting experience a moment of “sheer delight,” but a more accurate description would also include shock and a brief inability to breathe. If you are at risk for any sort of cardiac attack, this might not be your best choice.

If you want to really push your luck, sign up for a Platza Oak Leaf treatment, a traditional Russian treatment in which a spa attendant will lay you down, take a bundle of oak leaves soaked in olive oil soap, and beat you. (The leaves, which are naturally astringent, exfoliate the skin and open the pores.) More often than not, this treatment will occur in the Russian sauna itself, which means that not only will it be observed by everyone in the room, but that, oppressed by the heat, you might suffocate. Then, just before you pass out, your body will be subjected to its final shock: the attendant will have you sit up, close your eyes, and, without warning, slowly pour two buckets of ice water over your head.

N

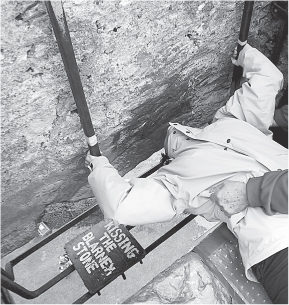

o one is really sure where the Blarney Stone came from. Some say it could have been part of Jerusalem’s Wailing Wall, brought to Ireland during the Crusades. Others claim it’s a piece of the Stone of Scone given to Cormac MacCarthy in 1314 to thank him for his help in the Battle of Bannockburn. Some even think it’s the rock that Moses struck with his staff to provide water to the Israelites. “Whatever the truth of its origin, we believe a witch saved from drowning revealed its power to the MacCarthys,” the Blarney Castle Web site announces, simultaneously dodging the question and discrediting itself as a reliable source of information.

Regardless of which, if any, of these rumors are true, there’s still no explanation for why a stone of such importance would have been inconspicuously incorporated into the exterior wall of a fifteenth-century castle. But that’s not the point. Set into the battlements of Blarney Castle, about five miles from the Irish town of Cork, the block of bluestone is said to bestow anyone who kisses it with great eloquence and talent in empty flattery. So for over two hundred years, pilgrims from around the world have been planting wet ones on the stone’s surface in hopes that they too will be blessed with the so-called “gift of gab.”

Unfortunately for would-be orators, the stone does not lend itself naturally to public displays of affection. Reaching it requires climbing to the top of the castle, leaning backward over a parapet, and dangling much of your body in the air, angling for a kiss as you gaze at the ground looming several stories below. In the good old days before liability waivers, visitors were held by the ankles and lowered headfirst over the wall. Now there are metal rails to help support and guide you, and a protective grate that prevents uncoordinated tourists from falling to their deaths.

The stone’s actual powers are debatable, but one thing’s for sure—the Blarney Stone is a germaphobe’s nightmare. Kissed by more than four hundred thousand people per year, it’s covered with trace bits of spit left behind with every pucker. Smooching it might not give you the gift of gab, but you could take home a different souvenir: a saliva-transmitted affliction like herpes, warts, or glandular fever. At least you’re safe from meningitis—to get it from kissing, you’d have to use a lot of tongue.

Wikipedia Commons