Catherine Howard (28 page)

24. and 25. The Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula and the site of the scaffold on Tower Green, where Catherine was beheaded by a single axe blow on

Manuscripts are cited and their location given under their usual abbreviations, which are as follows:

P.R.O. – Public Record Office,

London

S.P. 1 – State Papers, Henry VIII

S.P. 6 – Theological Tracts, Henry VIII

Star Chamber 2

Inquisitions Post Mortem C 142

In the citation of printed books, the following abbreviations have been used:

Antiq. Rep

. –

Antiquarian Repertory

B.M. –

British

Museum

Cal.

S.P. Spanish

–

Calendar of State Papers, Spanish

Cal.

S.P. Venetian

–

Calendar of State Papers, Venetian

Cam

. Soc. –

Camden

Society

Essex

Arch. Soc. Trans

. –

Essex

Archaeological Society Transactions

D.N.B

. –

Dictionary of National Biography

E.E.T.S. – Early English Text Society

H.O

. –

Ordinances of the Household

H.M.C. – Historical Manuscript Commission

H.S. – Harleian Society

J.H.I.

–

Journal of the History of Ideas

L.P

. –

Letters and Papers of Henry VIII

P.P.C

. –

Proceedings of the Privy Council

P.C.C. – Prerogatove Court at Cantebury (

Somerset

House)

Surrey

Arch. Col. –

Surrey

Archaeological Collections

Surrey

Arch. Soc. Trans. –

Surrey

Archaeological Society Transactions

Sussex

Arch. Col. –

Sussex

Archaeological Collections

St. Papers – State Papers during the Reign of Henry VIII

V.C.H. –

Victoria

County

History

Fuller titles, names of editors, and dates of editions are given in the bibliography of printed books. Spelling and punctuation of manuscript quotations have been modernized.

There are several ways of computing Catherine’s age. None of them is very conclusive and all are highly controversial. The only statement that can be made with any degree of reliability is that there are at least three contemporary reports that suggest that Catherine was unusually young at the time of her marriage to the King in July of 1540 (Hume,

Chronicle of Henry VIII

, p. 75;

Original Letters

, I, p. 201;

L.P

., XVI, 1426). What this signifies is difficult to say. Catherine’s mother was twelve when she married Ralph Legh, her first husband. Girls tended to be ‘forward virgins’ at fourteen, and childbearing began between sixteen and eighteen. On the other hand, in comparison with Henry’s other wives, Catherine need not have been a child bride of fifteen to warrant the description of a young woman. Catherine of Aragon was twenty-five at her marriage; Catherine Parr was at least thirty; Anne of Cleves, Anne Boleyn and Jane Seymour ranged between twenty-five and twenty-six, which represented by sixteenth-century standards the age of discretion and experience.

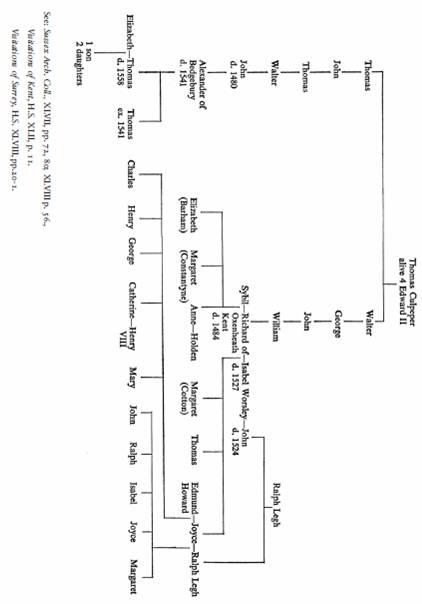

There are, however, certain outside limits that can be set with reasonable accuracy as the extremes within which Catherine’s birth must have fallen. She could not have been born after 1527, since Dame Isabel Legh, Catherine’s maternal grandmother, mentions her in her will of that year (18 Porch). Four years earlier, in 1524, John Legh, husband to Isabel and Catherine’s step-grandfather, failed to notice in his will the existence of any of the Howard girls. Instead he listed Catherine’s three brothers – Charles, Henry, and George (15 Bodfield). This may have been because Catherine and her sister Mary were not yet born, or it may have been a reflection of the masculine standards of the age – infant girls did not warrant mention as beneficiaries in a will.

The earliest limit is harder to determine, since the marriage date of Edmund Howard to Jocasta Culpeper is far from certain. If Edmund and Jocasta were wedded sometime around 1514-15 (

D.N.B

., article: ‘Catherine Howard’;

L.P

., 2nd edn., I, ii, 3325; Strickland,

Queens of England

, III, p. 101), and if her three brothers were her elders, as the genealogical tables suggest (

Visitations of Kent

, H.S., LXXIV, p. 81) then Catherine could not have been born before 1517-18.

There is considerable evidence for the belief that she was, in fact, born some time between 1518 and 1524. The French Ambassador reported that she was eighteen when she was sharing her bed with Francis Dereham (

L.P.,

XVI, 1426). The date of this affair, by Catherine’s own confession, was in 1538-9 (H.M.C.,

Marquis of Bath

, II, pp. 8-9). On the other hand, the Ambassador weakens the credence of his statement by adding that Dereham had been systematically corrupting Catherine ever since she was thirteen. If we accept her age as being eighteen in 1539, then she must have been born about 1521. The unknown author of the

Chronicle of Henry VIII

(p. 75), whose imagination is considerably better than his facts, says that the Queen was fifteen when she first encountered the King. This would push her birth forward to 1524.

There is one final clue: Catherine’s portrait (

Toledo

Museum

,

Toledo

,

Ohio

), about which there is considerable uncertainty, gives her age as twenty-one. Presumably it was painted in 1540 or 1541, and this would establish her birth in 1519 or 1520. The year 1521 seems as good as any, since we know that Henry Manox was first smitten by Catherine’s charms in 1536 when she would have been a precocious thirteen or fourteen. This in turn fits with the report of the French Ambassador, who claimed her age as eighteen in 1539, and with the general suggestion that Catherine was relatively young to have been a queen.

All of this is of course pure speculation, since, among other things, her father’s marriage in 1514-15 is conjectural, the statement that Catherine was the fifth child of the marriage is probably a guess on the part of Miss Strickland, since she does not bother to authenticate the statement (

Queens of England

, III, p. 101; see also

Visitation of

Kent

, H.S., LXXIV, p. 81). Finally there is hopeless confusion over how many full and half brothers and sisters Catherine actually had. This last complication arises out of the fact that Jocasta Culpeper was married twice – first to Ralph Legh (by whom she certainly had two sons, John and Ralph, and very probably three daughters, Isabel (who married Sir Edward Baynton), Joyce (who wedded John Stanney), and Margaret (who married first Thomas Arundel and possibly at a later date a gentleman named Rice). Her second marriage was to Edmund Howard (who sired Charles, Henry, George, and Catherine). Mary Howard, who married Sir Edmund Trafford, was probably a Howard child also, but she is claimed by both families, and there is some evidence that there was still a fourth Howard daughter named Margaret, but this may simply be a confusion with Margaret Legh. All we know for certain is that Edmund Howard was claiming ten children in 1527 (Ellis,

Letters

, I, 3rd series, 160). For those who wish to try their hand at this muddle over Catherine’s vital statistics, a start can be made by consulting the following: P.C.C., 15 Bodfield, 24 Bennet, 3 Crymes, 18 Porch, all of which are printed in the

Surrey Archaeological Collections

, LI, pp. 85-90;

Visitations of Cornwall

(edit. J. L. Vivian), pp. 4-5;

Inquisitions Post Mortem

,

Henry VIII

, I. 820;

Archaeologia Cantiana

, IV, p. 264;

Visitations of

Surrey

, H.S., XLIII, pp. 20-1;

Visitation of

Kent

, H.S., LXXIV: pp. 41-2 and 81 ;

V.C.H., History of Hampshire

, IV, pp. 185, 295-6;

Remains, Historical and Literary of

Lancaster

and

Chester

, Chetham Society, LI, p. 72; LXXXI, p. 3 ; Strickland,

Queens

of

England

, III, p. 101; D.N.B., art. ‘Catherine Howard’; H. Howard,

Memorials of the Howard Family

, pp. 1-26.