Carrier (1999) (56 page)

Authors: Tom - Nf Clancy

After the tour, I headed down to the commodore’s stateroom and sleep. John and I were scheduled to return to the

GW

in the morning, as we had been hearing rumors that the “hot war” part of the JTFEX scenario might start within a day or two. I had wanted to be aboard the

GW

when that happened in order to have the best possible view of the start of the hostilities. As it happened, things didn’t work out according to schedule—to our great good fortune, for we ended up experiencing the most interesting day of the exercise.

GW

in the morning, as we had been hearing rumors that the “hot war” part of the JTFEX scenario might start within a day or two. I had wanted to be aboard the

GW

when that happened in order to have the best possible view of the start of the hostilities. As it happened, things didn’t work out according to schedule—to our great good fortune, for we ended up experiencing the most interesting day of the exercise.

Saturday, August 23rd, 1997

JTFEX 97-3—Day 6: The Koronan government today continued to pressure Kartuna by test firing several SCUD ballistic missiles on their test range. This is seen as a sign that they are bringing their theater ballistic missile combat units to a high state of combat readiness. In addition, the Koronan fleet has been surged out of their ports, and is currently moving into position to track and trail the Coalition Naval forces massing in the Gulf of Sabani. Meanwhile, elements of the 24th MEU (SOC) and Guam ARG have commenced their NEO of the American embassy compound in Temal. It is expected that this operation will be completed early on the morning of August 24th.

By Saturday morning, much had happened in JTFEX 97-3. Overnight, the

Normandy

and the other escorts had rejoined the

GW,

and the combined battle group had entered the northern end of the Gulf of Sabani. Passing by the (imaginary) Willo and Hirt Islands, the group turned south into the Gulf to support the

Guam

ARG/24th MEU (SOC) in their NEO of endangered personnel from Kartuna.

Normandy

and the other escorts had rejoined the

GW,

and the combined battle group had entered the northern end of the Gulf of Sabani. Passing by the (imaginary) Willo and Hirt Islands, the group turned south into the Gulf to support the

Guam

ARG/24th MEU (SOC) in their NEO of endangered personnel from Kartuna.

Meanwhile, the USACOM J-7 exercise leaders were working hard on the “flex” part of the scenario, trying to bait Admiral Mullen and his commanders into actions that would cause hostilities to break out immediately. For the admiral and his staff, their job was to keep a “lid” on the scenario for as long as possible—important in the light of the NEO the 24th MEU (SOC) which had begun in the predawn hours. Here was to be the “eyeball-to-eyeball” phase of the exercise, simulating the “short-of-war” realities that our commanders would face in an actual crisis. Even though this was a training exercise, you could feel the tension of the emerging situation. Everyone in the battle group knew that they were being evaluated for their readiness to go into a potential combat situation during JTFEX 97-3, and nobody wanted to let the rest of the force down.

All around the battle group, ships from the Atlantic Fleet were being used to simulate Koronan Naval vessels in an “aggressor” role. And numerous other ships were simulating neutral shipping traffic, trying to get clear of the emerging fracas, or to get one more cargo run in before the “war” started. The final proof that the “hot” phase of the exercise was about to begin arrived on a UH-46 transport helicopter’s morning run in the form of the

Normandy’s

SOOT team representative. This was Captain James W. Phillips, the CO of the Aegis cruiser

Vella Gulf

(CG-72), who had come aboard to observe the proceedings and to evaluate the performance of Captain Deppe and his crew during the exercise. Captain Phillips is a courtly gentleman who quickly attached himself to Jim Deppe, and they were soon chatting away like two old friends working out the best place to catch a prize bass. But you only had to look out a porthole of the

Normandy’

s wardroom during breakfast to see that the game afoot in this pond beat the hell out of any fishing you might find ashore.

Normandy’s

SOOT team representative. This was Captain James W. Phillips, the CO of the Aegis cruiser

Vella Gulf

(CG-72), who had come aboard to observe the proceedings and to evaluate the performance of Captain Deppe and his crew during the exercise. Captain Phillips is a courtly gentleman who quickly attached himself to Jim Deppe, and they were soon chatting away like two old friends working out the best place to catch a prize bass. But you only had to look out a porthole of the

Normandy’

s wardroom during breakfast to see that the game afoot in this pond beat the hell out of any fishing you might find ashore.

Things were about to get very interesting in this little patch of the Gulf of Sabani. About 1,000 yards/914 meters off the starboard beam, a

Normandy

whaleboat was taking a maritime inspection team to the frigate

Samuel Elliot Morrison

(FFG-13), which was currently playing the part of a neutral merchant ship. Breakfast was hardly finished when the word came over that the frigate had a real casualty who needed to be evacuated back to the mainland, an action that caused a problem for John and myself. The diagnosis was hepatitis, and the patient was being transported over in the whaleboat with a corpsman.

Normandy

whaleboat was taking a maritime inspection team to the frigate

Samuel Elliot Morrison

(FFG-13), which was currently playing the part of a neutral merchant ship. Breakfast was hardly finished when the word came over that the frigate had a real casualty who needed to be evacuated back to the mainland, an action that caused a problem for John and myself. The diagnosis was hepatitis, and the patient was being transported over in the whaleboat with a corpsman.

With only a single HS-11 sortie scheduled to fly from

Normandy

to

GW

that day, this meant that the casualty and corpsman would take our places on the Seahawk, and we would have to wait another day or two to return to the carrier. Captain Deppe made it clear that he would do his best to get us back as soon as possible. And besides, he went on to say, there was plenty of room for us aboard, and since it was Saturday in the “real” world, it would be pizza night on the

Normandy.

Since

Normandy

had one of the best galleys in the Atlantic Fleet, this sounded like making the best of a bad situation.

Normandy

to

GW

that day, this meant that the casualty and corpsman would take our places on the Seahawk, and we would have to wait another day or two to return to the carrier. Captain Deppe made it clear that he would do his best to get us back as soon as possible. And besides, he went on to say, there was plenty of room for us aboard, and since it was Saturday in the “real” world, it would be pizza night on the

Normandy.

Since

Normandy

had one of the best galleys in the Atlantic Fleet, this sounded like making the best of a bad situation.

After the HS-11 Seahawk arrived and collected the casualty and corpsman, the ship passed into a comfortable high-pressure zone, which had the effect of dropping the temperature to a refreshing 80° F/27° C, and drying out the air to a sparkling clarity. Visibility became almost unlimited, with line-of-sight ranges running to almost 30,000 yards/27,400 meters. It soon became the most beautiful day I’d seen in months, with a flat calm sea and almost no wind. Meanwhile, the “bubble” of visible space around us had become crowded with ships.

Later that afternoon, around 1600 (4 P.M.), as I stood on the helicopter platform aft, I noticed something strange. One of the nearby ships suddenly closed from astern to around 2,000 yards/1,828 meters, and tried to move around us, much as a car tries to pass a truck on an interstate highway. A moment later, I felt the deck shudder underneath my feet, and heard the sharp whine of the

Normandy’s

four LM-2500 gas turbines going to full power. In just seconds the cruiser jumped from twelve to thirty knots, and Captain Deppe radically cut in front of the other ship, blocking the pass. Somewhat dazzled by this maneuver, I looked aft at the other vessel, a

Spruance-

class destroyer that I initially expected to be the USS

John Rodgers

(DD-983) from our battle group. But then I noticed that this

Spruance

did not have the ASROC launcher of the

John Rodgers,

and a quick glance at her pennant number confirmed my suspicions. It was the USS

Nicholson

(DD-982)—a VLS-equipped

Spruance

simulating a Koronan

Kashin-

class guided-missile destroyer. Clearly the JTFEX 97-3 scenario was growing hotter. John and I headed forward to the bridge at a dead run to find out what was going on.

Normandy’s

four LM-2500 gas turbines going to full power. In just seconds the cruiser jumped from twelve to thirty knots, and Captain Deppe radically cut in front of the other ship, blocking the pass. Somewhat dazzled by this maneuver, I looked aft at the other vessel, a

Spruance-

class destroyer that I initially expected to be the USS

John Rodgers

(DD-983) from our battle group. But then I noticed that this

Spruance

did not have the ASROC launcher of the

John Rodgers,

and a quick glance at her pennant number confirmed my suspicions. It was the USS

Nicholson

(DD-982)—a VLS-equipped

Spruance

simulating a Koronan

Kashin-

class guided-missile destroyer. Clearly the JTFEX 97-3 scenario was growing hotter. John and I headed forward to the bridge at a dead run to find out what was going on.

As we arrived on the port bridge wing, I saw the

Nicholson

trying to slip up our beam. Over at the edge of the bridge were Captains Deppe and Phillips, watching intently as the destroyer maneuvered. At the same time, the TBS (Talk Between Ship) radio circuit came alive with traffic from all around the battle group. Two frigates simulating Koronan guided-missile gunboats were maneuvering aggressively. Looking to one of the young lieutenants, I asked, “What the hell is going on?”

Nicholson

trying to slip up our beam. Over at the edge of the bridge were Captains Deppe and Phillips, watching intently as the destroyer maneuvered. At the same time, the TBS (Talk Between Ship) radio circuit came alive with traffic from all around the battle group. Two frigates simulating Koronan guided-missile gunboats were maneuvering aggressively. Looking to one of the young lieutenants, I asked, “What the hell is going on?”

“They’re playing chicken,” he said, “like the Russians.” The remark was like a trip through time for me.

Back in the Cold War, the ships and submarines of the Soviet Navy used to trail our CVBGs the way

Nicholson

was doing. This was a favorite tactic of the late Admiral Sergei Gorshkov (the longtime chief of the Soviet Navy), and took advantage of the “freedom of navigation” rules accorded ships on the high seas. The idea was to maneuver for a clear line of sight to the carrier the way they’d do just before the outbreak of a real conflict. In the “first salvo” of that war, the ships and subs would fire their missiles, torpedoes, and guns and attempt to put the flattop out of action. The only way to defeat this threat was for our own escort ships to maneuver aggressively, physically placing themselves between the enemy ships and the carrier. At times, vessels of both sides would actually “bump.” Such aggressive maneuvering now and then increased tensions between the superpowers.

78

We used to call it “Cowboys and Russians,” and I had thought that it was a thing of the past. 1 was clearly wrong.

Nicholson

was doing. This was a favorite tactic of the late Admiral Sergei Gorshkov (the longtime chief of the Soviet Navy), and took advantage of the “freedom of navigation” rules accorded ships on the high seas. The idea was to maneuver for a clear line of sight to the carrier the way they’d do just before the outbreak of a real conflict. In the “first salvo” of that war, the ships and subs would fire their missiles, torpedoes, and guns and attempt to put the flattop out of action. The only way to defeat this threat was for our own escort ships to maneuver aggressively, physically placing themselves between the enemy ships and the carrier. At times, vessels of both sides would actually “bump.” Such aggressive maneuvering now and then increased tensions between the superpowers.

78

We used to call it “Cowboys and Russians,” and I had thought that it was a thing of the past. 1 was clearly wrong.

Though it’s not publicized by the U.S. Navy, the tactic of interposing an escort ship between an opponent and the carrier is still practiced; it resembles the “hassling” that fighter pilots engage in to keep themselves sharp. But “dogfighting” with billion-dollar cruisers and destroyers is riskier. Clearly the USACOM training staff wanted to stress Admiral Mullen and his staff into a situation where the Koronan forces could claim a provocation and initiate hostilities while the 24th MEU (SOC) was still conducting their NEO in Temal. The challenge was clear. If a Koronan ship was able to draw a line-of-sight bead on the GW, then the escorts would be required to “fire” on the offending vessel to keep the flattop safe. At the same time, because

GW

was conducting flight operations, there was very little Captain Rutheford could do to help combat the intruders.

GW

was conducting flight operations, there was very little Captain Rutheford could do to help combat the intruders.

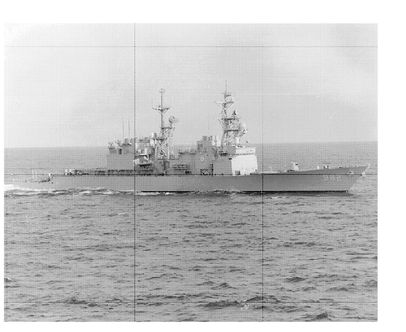

The destroyer USS

Nicholson

(DD-982), during her maneuvering duel with the USS

Normandy

(CG-60).

Nicholson

(DD-982), during her maneuvering duel with the USS

Normandy

(CG-60).

JOHN D. GRESHAM

For the next few hours, it would be up to the “small boys” of the battle group to keep the Koronan missile ships at bay. Clearly, the

Normandy’s

Saturday night pizza tradition was about to go on hold for a while. Captain Deppe, immediately grasping the challenge, went to the task with a grin on his face. Opportunities were rare to maneuver his ship to its limits against a fellow skipper in an almost perfectly matched ship. This was just such a chance. Although there are clear exercise rules about how close opposing combatants are allowed to approach, these rules were about to be bent. In fact, the only rule seemed to be: Don’t actually

touch

the other guy!

Normandy’s

Saturday night pizza tradition was about to go on hold for a while. Captain Deppe, immediately grasping the challenge, went to the task with a grin on his face. Opportunities were rare to maneuver his ship to its limits against a fellow skipper in an almost perfectly matched ship. This was just such a chance. Although there are clear exercise rules about how close opposing combatants are allowed to approach, these rules were about to be bent. In fact, the only rule seemed to be: Don’t actually

touch

the other guy!

The next few hours went by very quickly, as we parried and thrusted with the

Nicholson.

The captain of the

Nicholson

(Commander Craig E. Langman) was extremely aggressive, doing everything he could to get past us. He never succeeded. Captain Deppe maneuvered the

Normandy

like a Formula I racing car, keeping the destroyer solidly away from the flattop. At times we raced ahead at over thirty knots, only to crash-stop within a ship length or two. Then we might sit for ten or fifteen minutes, with just a thousand yards or so separating the two vessels. Suddenly, the

Nicholson

would jam on the speed, and the maneuvering would begin again. Each time, Captain Deppe would match his counterpart move-for-move. At times the

Normandy

would heel as much as 40°, and you could hear the sounds of pizza pans and crockery hitting the deck back in the galley. Other times, it would be a race to see if the

Nicholson

could inch ahead just a little, followed by a radical turn to try to gain position.

Nicholson.

The captain of the

Nicholson

(Commander Craig E. Langman) was extremely aggressive, doing everything he could to get past us. He never succeeded. Captain Deppe maneuvered the

Normandy

like a Formula I racing car, keeping the destroyer solidly away from the flattop. At times we raced ahead at over thirty knots, only to crash-stop within a ship length or two. Then we might sit for ten or fifteen minutes, with just a thousand yards or so separating the two vessels. Suddenly, the

Nicholson

would jam on the speed, and the maneuvering would begin again. Each time, Captain Deppe would match his counterpart move-for-move. At times the

Normandy

would heel as much as 40°, and you could hear the sounds of pizza pans and crockery hitting the deck back in the galley. Other times, it would be a race to see if the

Nicholson

could inch ahead just a little, followed by a radical turn to try to gain position.

It wasn’t until sometime after 2000 (8 P.M.) that the

Nicholson

and the other two Koronan intruders finally turned away, and the jousting was over. As Captain Deppe ordered the engines throttled back and began to con the

Normandy

to her assigned position in the defense screen, Admiral Mullen’s voice came up on the TBS circuit. For several minutes, the admiral commented on the performance of each ship in the screen, after which he paid a glowing compliment to the skippers of the three escorts that had fended off the Koronan warships. After his hearty “Well done,” you could feel the tension ease around the ship. Though we did not know it at the time, the

GW

battle group had passed a significant test; they had bought two more days of “peace” for the Kartunans and their coalition allies.

Nicholson

and the other two Koronan intruders finally turned away, and the jousting was over. As Captain Deppe ordered the engines throttled back and began to con the

Normandy

to her assigned position in the defense screen, Admiral Mullen’s voice came up on the TBS circuit. For several minutes, the admiral commented on the performance of each ship in the screen, after which he paid a glowing compliment to the skippers of the three escorts that had fended off the Koronan warships. After his hearty “Well done,” you could feel the tension ease around the ship. Though we did not know it at the time, the

GW

battle group had passed a significant test; they had bought two more days of “peace” for the Kartunans and their coalition allies.

Aboard the

Normandy,

life began to settle back to normal. Down in the galleys, the mess specialists salvaged what they could of the pizzas they would serve at mid-rats. Though the 2300 (11 P.M.) feeding was heavy that night, many of the officers and crew chose to just hit their racks and grab some sleep instead. These were the veterans, who knew that what they had seen today was only the beginning of what could be another two weeks of “combat.” Those with less experience and more adrenaline munched on thick-crust pan pizza, and chatted about the terrific ship-handling Captain Deppe had shown the entire battle group that day. As I lingered over a piece of the baked pie, I answered a question that had been in my mind for some time: Since the end of the Cold War, the surface forces of the USN have not had a serious enemy. Such a condition can breed complacency and lead to “sloppy” habits in commanders and crews. Jim Deppe’s performance on the bridge of the

Normandy

this Saturday evening convinced me that

our

surface Navy still has “the right stuff.”

Normandy,

life began to settle back to normal. Down in the galleys, the mess specialists salvaged what they could of the pizzas they would serve at mid-rats. Though the 2300 (11 P.M.) feeding was heavy that night, many of the officers and crew chose to just hit their racks and grab some sleep instead. These were the veterans, who knew that what they had seen today was only the beginning of what could be another two weeks of “combat.” Those with less experience and more adrenaline munched on thick-crust pan pizza, and chatted about the terrific ship-handling Captain Deppe had shown the entire battle group that day. As I lingered over a piece of the baked pie, I answered a question that had been in my mind for some time: Since the end of the Cold War, the surface forces of the USN have not had a serious enemy. Such a condition can breed complacency and lead to “sloppy” habits in commanders and crews. Jim Deppe’s performance on the bridge of the

Normandy

this Saturday evening convinced me that

our

surface Navy still has “the right stuff.”

Sunday, August 24th, 1997

JTFEX 97-3-Day 7: The 24th MEU (SOC) completed their NEO early today, and is evacuating the civilians to a neutral location. The aggressive actions of Koronan Naval forces yesterday have been reported to the UN Security Council, which has issued an additional resolution allowing expanded use of force in the event of further harassment. The only Koronan government response has been additional mobilization of their military forces.

Other books

Dreamscape: Saving Alex by Kirstin Pulioff

When an Alpha Purrs by Eve Langlais

Unos asesinatos muy reales by Charlaine Harris

Soldiers in Heat: Training Session by Joanna A. Haze

What We Keep by Elizabeth Berg

The Godmakers by Frank Herbert

First degree by David Rosenfelt

When I Was Mortal by Javier Marias

Summoning Shadows: A Rosso Lussuria Vampire Novel by Pennington, Winter

Best Black Women's Erotica by Blanche Richardson