Carrier (1999) (55 page)

Authors: Tom - Nf Clancy

Soon after we had crowded aboard and were strapped in, the crew got ready to take off. But as the pilot ran through his checklist and throttled up, he got a warning light indicating a problem in one of the T700 engines. Quickly, both power plants were shut down, and we were asked to leave the aircraft and head back over to the island. By this time thoroughly soaked, we descended back to the O-2 level and the ATO office, while flight deck crews cleared the broken bird from the deck and started up the next flight event. Within minutes, the voice of Air Boss John Kindred boomed over the flight deck PA system, soon followed by the roars of jet engines and the screech of catapults.

As we stripped off our soaked survival gear, the ATO personnel handed us dry towels and cold drinks. Then we sat down to wait. Fifteen minutes later, we were told that the

Normandy

would launch one of her own SH-60B Seahawks, which would collect us following the flight event currently under way. The bad news was that it would take at least three hours before they could land aboard the

GW.

We had a long wait ahead of us. The good news was that this would give us a chance to talk with Captain Deppe, and get some feel about how he and his ship were being used by Admiral Mullen.

Normandy

would launch one of her own SH-60B Seahawks, which would collect us following the flight event currently under way. The bad news was that it would take at least three hours before they could land aboard the

GW.

We had a long wait ahead of us. The good news was that this would give us a chance to talk with Captain Deppe, and get some feel about how he and his ship were being used by Admiral Mullen.

As CO of one of the most capable Anti-Air Warfare (AAW) platform in the fleet, Deppe had been assigned the job of AAW coordinator for the entire force. Since most of the other warfare functions coordinators (ASW, Anti-Surface Warfare (ASUW), etc.) were based aboard the GW, and the

Normandy

had nothing like the secure, wide-bandwidth satellite communications systems that would allow secure teleconferencing, he had to make the commute over to the GW almost daily. This was necessary in order to attend secure conferences among the officers responsible for the battle group’s defense. Add to this the relative novelty of the battle group tactics being practiced by Admiral Mullen, and you have Jim Deppe spending several hours in the air each day going back and forth between

Normandy

and “Blue Tile Land” in

GW.

This new way of running a CVBG is an extremely “hands on” way of doing business, and until new wide-bandwidth satellite telecommunications systems become more common in the fleet, you’re going to see a lot of ship COs flying back and forth between ships.

Normandy

had nothing like the secure, wide-bandwidth satellite communications systems that would allow secure teleconferencing, he had to make the commute over to the GW almost daily. This was necessary in order to attend secure conferences among the officers responsible for the battle group’s defense. Add to this the relative novelty of the battle group tactics being practiced by Admiral Mullen, and you have Jim Deppe spending several hours in the air each day going back and forth between

Normandy

and “Blue Tile Land” in

GW.

This new way of running a CVBG is an extremely “hands on” way of doing business, and until new wide-bandwidth satellite telecommunications systems become more common in the fleet, you’re going to see a lot of ship COs flying back and forth between ships.

It was almost 1500 (3 P.M.) by the time the last of the CVW-1 aircraft were brought aboard, and the waist helicopter landing spots cleared. The HSL-48 Seahawk had circled the

GW

for almost an hour, and the crew was clearly in a hurry to get back home, approximately 100 miles/161 kilometers away. By this time, the squall had cleared enough for us to cross the flight deck without getting soaked. This time, the preflight checks all went well, and within minutes, the crew was cleared to launch. After we lifted off, we headed east to rendezvous with the

Normandy.

Flying at around 1,500 feet/ 457 meters altitude, we stayed below the cloud base and ran flat out to the east. About halfway to the cruiser, I looked out a window and saw below a dirty brown streak in the water spreading out for miles. When I asked the crew chief about it, he frowned. “Pollution,” he said. Some ship had passed through and pumped its bilge into the blue of the Atlantic. It occurred to me just then that an antiship missile might come in handy—

pour

encourager les

autres.

GW

for almost an hour, and the crew was clearly in a hurry to get back home, approximately 100 miles/161 kilometers away. By this time, the squall had cleared enough for us to cross the flight deck without getting soaked. This time, the preflight checks all went well, and within minutes, the crew was cleared to launch. After we lifted off, we headed east to rendezvous with the

Normandy.

Flying at around 1,500 feet/ 457 meters altitude, we stayed below the cloud base and ran flat out to the east. About halfway to the cruiser, I looked out a window and saw below a dirty brown streak in the water spreading out for miles. When I asked the crew chief about it, he frowned. “Pollution,” he said. Some ship had passed through and pumped its bilge into the blue of the Atlantic. It occurred to me just then that an antiship missile might come in handy—

pour

encourager les

autres.

Soon our new home, the Aegis cruiser USS

Normandy,

came into view. Steaming into the wind, she was making ready to take us aboard. The deck crews were making quick work of it. After just a single circle of the cruiser, the pilot ran up the wake of the ship, matched his speed to the ship’s, and hovered over the helicopter deck. At this point, the crew chief winched down a small line with a “messenger” attachment at the end. When it reached the deck below us, a deck crewman scampered across to the messenger and inserted it into the clamp of the ship’s Recovery, Assist, Secure, and Traversing (RAST) system—a system of mechanical tracks in the deck of the ship’s helicopter pad. The clamp, which runs on the tracks, is designed to hold the messenger at the end of the line. The helicopter can then be winched down safely and securely onto the deck, even in heavy seas. Soon, we found ourselves on deck, and Captain Deppe was rushing up to the bridge.

Normandy,

came into view. Steaming into the wind, she was making ready to take us aboard. The deck crews were making quick work of it. After just a single circle of the cruiser, the pilot ran up the wake of the ship, matched his speed to the ship’s, and hovered over the helicopter deck. At this point, the crew chief winched down a small line with a “messenger” attachment at the end. When it reached the deck below us, a deck crewman scampered across to the messenger and inserted it into the clamp of the ship’s Recovery, Assist, Secure, and Traversing (RAST) system—a system of mechanical tracks in the deck of the ship’s helicopter pad. The clamp, which runs on the tracks, is designed to hold the messenger at the end of the line. The helicopter can then be winched down safely and securely onto the deck, even in heavy seas. Soon, we found ourselves on deck, and Captain Deppe was rushing up to the bridge.

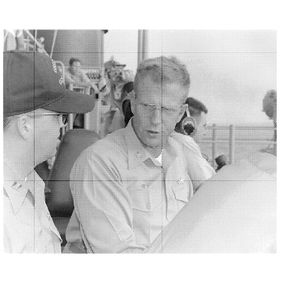

Captain Jim Deppe, the CO of USS

Normandy

(CG-60), cons his ship while refueling under way from the USS

Seattle

(AOE-3).

Normandy

(CG-60), cons his ship while refueling under way from the USS

Seattle

(AOE-3).

JOHN D. GRESHAM

The reason for his hurry was quickly evident. The huge bulk of the USS

Seattle,

the GW battle group’s fleet replenishment ship, was showing on the horizon. We had arrived just in time for him to take over the delicate and sometimes difficult job of conning the ship while replenishing under way. After leaving our bags for the deck crews to take to our quarters, we followed him to the bridge—not an easy undertaking. To reach the top of the cruiser’s massive deckhouse requires climbing some seven ladders. The effort was worth it, though, for up there we had a splendid view of one of the most beautiful dances performed by U.S. Navy ships.

Seattle,

the GW battle group’s fleet replenishment ship, was showing on the horizon. We had arrived just in time for him to take over the delicate and sometimes difficult job of conning the ship while replenishing under way. After leaving our bags for the deck crews to take to our quarters, we followed him to the bridge—not an easy undertaking. To reach the top of the cruiser’s massive deckhouse requires climbing some seven ladders. The effort was worth it, though, for up there we had a splendid view of one of the most beautiful dances performed by U.S. Navy ships.

I’ve always believed that the skill that separates great Navies from the also-rans is the ability to sustain a fleet at sea with underway replenishment (UNREP). Something of an American invention prior to World War II, UNREP is a little like an elephant ballet. The dynamics of conning a ship in close proximity to another are completely different from any other kind of ship handling, and Captain Deppe was about to give us a textbook lesson in the art.

Initially, he allowed Captain Stephen Firks, CO of the

Seattle,

to come up on

Normandy

and position his ship on the cruiser’s port (left) side. Once this was done, the

Seattle

began to shoot messenger lines across the gap to the deck crews of the

Normandy.

After these were recovered, the deck crewmen pulled larger lines across and began to rig the refueling lines. For this UNREP, only two refueling lines would be set, since only JP-5 jet fuel for the

Normandy

’s gas turbine engines and helicopters was being transferred, so there would not be any “high lines” for moving cargo or other supplies. There would also be no use of the

Seattle

’s UH-46 Sea Knight Vertical Replenishment (VERTREP) helicopters, as the

Normandy

was still well stocked with food and other consumables.

Seattle,

to come up on

Normandy

and position his ship on the cruiser’s port (left) side. Once this was done, the

Seattle

began to shoot messenger lines across the gap to the deck crews of the

Normandy.

After these were recovered, the deck crewmen pulled larger lines across and began to rig the refueling lines. For this UNREP, only two refueling lines would be set, since only JP-5 jet fuel for the

Normandy

’s gas turbine engines and helicopters was being transferred, so there would not be any “high lines” for moving cargo or other supplies. There would also be no use of the

Seattle

’s UH-46 Sea Knight Vertical Replenishment (VERTREP) helicopters, as the

Normandy

was still well stocked with food and other consumables.

Within ten minutes, the lines were rigged, and the refueling hoses were pulled across the hundred feet/thirty meters or so of space between the two ships. Each hose has a “male” probe, which locks into a “female” receptacle on the receiving ship. These can be rapidly disconnected in the event of an emergency, what the Navy calls a “breakaway.” When properly set and pressurized, each hose can move several thousand gallons a minute of distilled petroleum products. As soon as the refueling probes were secured into their receptacles, the

Seattle

began to pump JP-5 over to the cruiser. Gradually, the pressure was built up, and the flow increased.

Seattle

began to pump JP-5 over to the cruiser. Gradually, the pressure was built up, and the flow increased.

While all of this was going on, the two ship captains were carefully conning their vessels, making sure that the spacing and alignment remained constant. This can be difficult with ships of different sizes. Since the larger one wants to “suck” the smaller vessel into its side, maintaining station during UNREPs is a delicate business measured in an additional rpm or two of shaft power, or a twitch of propeller pitch. This afternoon all went exceedingly smoothly, and Captains Deppe and Firks (of

Seattle)

put on a show of ship handling that one could only admire.

Seattle)

put on a show of ship handling that one could only admire.

Part of the beauty of this operation is that it is done virtually without radio or other electronic signals. To keep things simple and quiet, only lights and flags are used. After about thirty minutes of refueling, the call came up from engineering that the

Normandy

’s fuel bunkers were full and the UNREP completed. As they uncoupled the hoses, the crews of both ships were careful to limit JP-5 spills into the sea, to minimize pollution. Not many of us realize how tough pollution-control rules are on the military, and how hard they work to be “green.” Once the hoses were retracted back to the

Seattle,

the deck crews began to strike their lines and drop them over the side to be retrieved by the oiler’s personnel. Now came one last ticklish operation.

Normandy

’s fuel bunkers were full and the UNREP completed. As they uncoupled the hoses, the crews of both ships were careful to limit JP-5 spills into the sea, to minimize pollution. Not many of us realize how tough pollution-control rules are on the military, and how hard they work to be “green.” Once the hoses were retracted back to the

Seattle,

the deck crews began to strike their lines and drop them over the side to be retrieved by the oiler’s personnel. Now came one last ticklish operation.

Captain Deppe ordered all ahead two thirds (about twenty knots/thirty-seven kilometers an hour), and then began a gradual turn to starboard, a maneuver designed to make the breakaway from the 53,000-ton oiler as smooth and easy as possible. Deppe ran the cruiser through a full 360° turn and almost 10,000 yards/9,144 meters of separation from the Seattle before he felt free to maneuver again. At the completion of this turn, he ordered the cruiser to head west to join up with some other ships of the GW battle group. After that, we all adjourned below to freshen up for dinner.

I was escorted to quarters usually reserved for an embarked flag officer—very luxurious after the cramped quarters of the

GW.

With only around 350 personnel, the

Normandy

is much more intimate and pleasant than the carrier. People can actually find privacy here and there on

Normandy

if they want it. Another nice thing about being on one of the “small boys” was the absence of the hundreds of extra VIPs, observers, media personnel, and contractors now on the carrier, making space and comfort more plentiful than aboard the

GW.

Perhaps the only thing I missed was the live video feeds from CNN and other networks provided by the onboard Challenge Athena system.

GW.

With only around 350 personnel, the

Normandy

is much more intimate and pleasant than the carrier. People can actually find privacy here and there on

Normandy

if they want it. Another nice thing about being on one of the “small boys” was the absence of the hundreds of extra VIPs, observers, media personnel, and contractors now on the carrier, making space and comfort more plentiful than aboard the

GW.

Perhaps the only thing I missed was the live video feeds from CNN and other networks provided by the onboard Challenge Athena system.

As we gathered in the

Normandy’s

wardroom for dinner, I was struck by the youth of Captain’s Deppe’s officers. While the department heads were mostly lieutenant commanders, most of the others were lieutenants with less than five years service. Escort duty is a young person’s profession, and around the table the majority of the faces were under thirty. Aboard the “small boys” of the cruiser/destroyer/frigate force, the officers’ wardroom is the center of their social world. The wardroom table is a place of open expression, with rank and position holding little sway. Here problems are discussed, assignments made, and professional experience passed along to young officers. There is

very

little formality. The only real rule is that everyone stands for the captain, and waits for him to serve himself before everyone else does so. As for the food, it’s as good as any you will find in the fleet. From the

Normandy

’s small galley came a mountain of edibles, including a fine salad bar and excellent baked chicken and rice. The only problem you’ll find is dealing with the roll of the ship. And therein lies a story.

Normandy’s

wardroom for dinner, I was struck by the youth of Captain’s Deppe’s officers. While the department heads were mostly lieutenant commanders, most of the others were lieutenants with less than five years service. Escort duty is a young person’s profession, and around the table the majority of the faces were under thirty. Aboard the “small boys” of the cruiser/destroyer/frigate force, the officers’ wardroom is the center of their social world. The wardroom table is a place of open expression, with rank and position holding little sway. Here problems are discussed, assignments made, and professional experience passed along to young officers. There is

very

little formality. The only real rule is that everyone stands for the captain, and waits for him to serve himself before everyone else does so. As for the food, it’s as good as any you will find in the fleet. From the

Normandy

’s small galley came a mountain of edibles, including a fine salad bar and excellent baked chicken and rice. The only problem you’ll find is dealing with the roll of the ship. And therein lies a story.

The

Ticonderoga-

class (CG-47) Aegis cruisers were built upon hulls originally designed for the

Spruance-

class (DD-963) general-purpose destroyers. They share a common structural hull power plant and many other systems. However, the extra load of weapons and other equipment associated with the Aegis combat system has definitely “maxed out” the original

Spruance

design. The

“Ticos,”

as they are known, displace fully 15% more than a

Spruance,

much of which is located in the tall deckhouses that mount the four big SPY-1 phased-array radars that are the heart of the Aegis system. What this all means is that the

Ticos

are top-heavy. Not enough to make them unstable or prone to capsizing, mind you; but enough to make them less than comfortable for those who don’t enjoy pitching, swaying, and rolling. In fact, they handle the seas quite well and maneuver like a small Italian sports car in the hands of a professional. However, they do roll a

lot!

In a heavy sea or sharp turn, they can heel up to 40° from the vertical. It is not particularly uncomfortable, and does not tend to cause motion sickness. However, it does make activities like eating meals potentially exciting. And for us that evening, more than once the ship took rolls steep enough to force us to grab hold of plates and serving dishes.

Ticonderoga-

class (CG-47) Aegis cruisers were built upon hulls originally designed for the

Spruance-

class (DD-963) general-purpose destroyers. They share a common structural hull power plant and many other systems. However, the extra load of weapons and other equipment associated with the Aegis combat system has definitely “maxed out” the original

Spruance

design. The

“Ticos,”

as they are known, displace fully 15% more than a

Spruance,

much of which is located in the tall deckhouses that mount the four big SPY-1 phased-array radars that are the heart of the Aegis system. What this all means is that the

Ticos

are top-heavy. Not enough to make them unstable or prone to capsizing, mind you; but enough to make them less than comfortable for those who don’t enjoy pitching, swaying, and rolling. In fact, they handle the seas quite well and maneuver like a small Italian sports car in the hands of a professional. However, they do roll a

lot!

In a heavy sea or sharp turn, they can heel up to 40° from the vertical. It is not particularly uncomfortable, and does not tend to cause motion sickness. However, it does make activities like eating meals potentially exciting. And for us that evening, more than once the ship took rolls steep enough to force us to grab hold of plates and serving dishes.

After dinner, we were given a tour of the engineering departments and combat center. While

Normandy

is almost ten years old (she was commissioned in 1989) and coming to the end of her second five-year operating period, she is in terrific shape. In fact, I was amazed how well her crew has maintained her. Everything was spotless, even the deck corners; and all the sensor and combat systems were “up” and ready for action.

Normandy

is almost ten years old (she was commissioned in 1989) and coming to the end of her second five-year operating period, she is in terrific shape. In fact, I was amazed how well her crew has maintained her. Everything was spotless, even the deck corners; and all the sensor and combat systems were “up” and ready for action.

Normandy

is representative of the “Baseline 3”

Ticos,

with improved lightweight SPY-1B radars (each Aegis ship has four of these) and new computers. Following the 1997/98 cruise, she will head into the yard for a major overhaul, which will completely update her Aegis combat system to the latest version. When she comes out of the yard sometime in 1999, she will be equipped with the new SM-2 Block 4 SAM, which will give her an ability to engage and destroy theater ballistic missiles (TBMs). Eventually, the entire fleet of Aegis cruisers and destroyers will have this capability, which will greatly reduce the risks from enemy TBMs to our forward-deployed forces. Today, the crew of the

Normandy

and the Aegis destroyer

Carney

were simulating some of the engagement techniques that will be part of that future capability.

is representative of the “Baseline 3”

Ticos,

with improved lightweight SPY-1B radars (each Aegis ship has four of these) and new computers. Following the 1997/98 cruise, she will head into the yard for a major overhaul, which will completely update her Aegis combat system to the latest version. When she comes out of the yard sometime in 1999, she will be equipped with the new SM-2 Block 4 SAM, which will give her an ability to engage and destroy theater ballistic missiles (TBMs). Eventually, the entire fleet of Aegis cruisers and destroyers will have this capability, which will greatly reduce the risks from enemy TBMs to our forward-deployed forces. Today, the crew of the

Normandy

and the Aegis destroyer

Carney

were simulating some of the engagement techniques that will be part of that future capability.

Other books

Shana Galen by True Spies

The Devil and Deep Space by Susan R. Matthews

A Deadly Affection by Cuyler Overholt

A Game of Cat & Mouse by Astrid Cielo

How to Heal a Broken Heart by Kels Barnholdt

The Answer to Everything by Elyse Friedman

Zombie Rules (Book 3): ZFINITY by Achord, David

The Unveiling (Work of Art #2) by Ruth Clampett

Love In The Time Of Apps by Jay Begler