Campari for Breakfast (8 page)

‘You didn’t know?’

‘We didn’t know, and Buddleia was naturally very upset.’

She continued, now unprompted, with a random confusion of memories.

‘Of course, looking back there were lots of things that didn’t make sense, but it happened just after the war you see, and you were just so glad to be alive then, you didn’t ask too many questions, especially if you had no reason not to believe what you’d been told.’

I looked out the window at a stray star which had forgotten itself in the daylight; it had an attitude of faint amusement at what it saw as a pin-prick story.

‘But if Cameo was my mother’s mother, then who was my mother’s father?’

‘His name was Major Jack Laine,’ said Aunt Coral, as though she’d just said his name was dog poo. ‘He abandoned Cameo and the baby.’

She put on her close-work glasses and unfolded the birth certificate for me, trying to be reassuring, but her gaze was anything but. ‘I’m so sorry I didn’t know,’ she said.

‘You mean you didn’t

notice

that your mother wasn’t pregnant with my mother, and that Cameo

was

?’ I said.

‘I was away at college; I wasn’t around to actually

see

.’

‘You didn’t go home for nine months?’

‘No, I

did

—’ She hesitated, as though someone had pressed her pause button, but I think it was only because she couldn’t believe it herself.

‘You see Nana Pearl had three miscarriages after having Cameo, so Buddleia seemed like a miracle because we thought she couldn’t have any more. And that winter was the coldest I can remember, everyone was very wrapped up. I only made it home once – there were no trains because there was no coal. I was told that Mother hadn’t known that she was pregnant. She was also prone to be stout. And then of course after Buddleia was born, she took her away to Australia. I didn’t quite understand why at the time, but now I think she was taking Buddleia away from the curiosity of the neighbours.’

I already knew that Grand Nana Pearl had left England after the war, taking mum ‘on a sabbatical’ to the Bush, and found she preferred a tea chest, billy can and camp fire to a dining room, chair and fine china.

‘But why did they pretend? It just seems bonkers,’ I said.

‘They were Victorians, respectability was everything. Marriage for a girl was the tops. It wouldn’t have been possible for Cameo with an illegitimate child. It wouldn’t have been accepted. It’s ironic that they went to all that trouble, when Cameo—’ She stopped for an involuntary moment.

‘When Cameo?’

‘When Cameo didn’t make it,’ she said, almost too choked to speak.

She was trying to put all her pieces together just as much as I was. I had the feeling I should not ask further about Cameo just then.

‘But the worst of it is Buddleia

didn’t believe

that I didn’t know Cameo’s secret,’ she said, ‘and some of her last words to me were unkind …’

‘At least you

have

some last words,’ I said. ‘I have nothing.’

‘Actually . . . you do have something.’ And then she opened out a piece of paper. I froze in horror to think she’d been withholding it. ‘Buddleia sent me

this

.’

‘Oh God,’ I said. I sat up in bed, my limbs without oomph, and read the letter in hunger, searching the next line for clues before I’d finished the one I was on.

June 12 1986

Dear Coral,

I just wanted to let you know where I have got to with things, which isn’t terribly far. The record books at St Catherine’s House are lodged in colour-coded sections within the building. Green for marriages, red for births and black for deaths. I have only found two Major Jack Laines, but one of them is deceased, and the other one is classified as ‘an idiot’. However there may be hundreds of other Major Laines out there who are still alive and unmarried, and who obviously weren’t born majors.

And so I am none the wiser as to who I am. The only one, it seems.

Buddleia

‘But this doesn’t tell us anything. This is a scrap of research about her real Dad. It isn’t a farewell, or an explanation of why she did what she did.’

‘But I think it is,’ said Aunt Coral. Her eyes were welling with the small filmy tears of a lady, though she fought them back.

‘Just imagine finding that your whole childhood has been a lie, that no one was who they said they were. Finding out your father is not your father, and that your

real

father, who you never knew, may be deceased or an idiot. I think it may be what drove her over the edge. And she died thinking that I knew the truth and didn’t tell her. But I

didn’t

know. It so presses on me.’

‘I understand, it’s called unfinished business,’ I said.

Then the pressure of holding in her emotions overcame her and she had to let go of her real tears, not her socially comfortable tears, but big painful tears that weren’t manageable. I had never till today seen Aunt Coral in such great distress.

‘I don’t understand why they kept it from me,’ she said, ‘but I suppose there comes a time with such secrets when it’s too late to tell the truth.’

‘So Major Laine, wherever he is, he’s my …’

‘He’s your Grandfather,’ said Aunt Coral.

‘But do you think he

knew

he was Mum’s Father?’ I said. ‘Do you think there’s a chance that he didn’t? Is there a law that says that fathers must be told?’

‘They’re all good questions, Sue, and the answer is I don’t know, but I rather assume he did know if Cameo named him so on the birth certificate. It was too late to retrieve anything else from the fire, otherwise there may have been correspondence in there that could have told us. Anyway, the upshot is, I have taken up the cudgels, and short of tracing every Laine in the country and asking if they’re a Major, I have started to comb through the phone books. There’s a Jeremy Laine on the borders, he’s a TV producer I think, and a Dave Laine out at Buswater. But I feel they are coincidental, so I’m going to place an ad in the

Echo

and see if that prompts someone to get in touch.’

‘I still don’t understand why Grampa Evelyn kept the certificate if he wanted it to be secret?’

‘Probably just in case. He must have had his reasons, though now we will never know them. No, I’m afraid that now this is the only record that I have of the past.’ She was referring to her Commonplace.

Then she pulled her threads back together, opened my window for fresh air and smoothed my appalling hair. She was back to being the strong one.

But it still doesn’t make sense to me of Mum’s decision to die, and most pertinently, of why she didn’t tell me, but Aunt Coral is convinced that we need look no further for a motive.

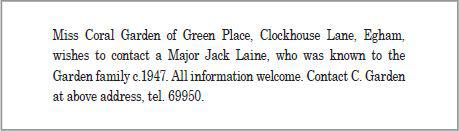

The Commonplace Book of Coral Garden: Volume 5

Newspaper cutting, ‘Personal Column’,

Egham Echo

, 23 Feb 1987:

The Commonplace Book of Coral Garden: Volume 1

Green Place, Christmas 1932

(Age ten)

News

Cameo has had a terrible accident. She fell three feet and a ski pole went through her eye. Mother cannot stop weeping. She gave Cameo a doll’s house for Christmas to help aid in her recovery. It is along the lines of the one made for Queen Mary, which set the doll’s house world alight, boasting Louis chairs, Chippendales, and working electric lights.

The surgeons have been measuring the risks of brain damage if they proceed with more surgery, and she is still in great pain. She may end up wearing a false eye. She had to have a big bald patch shaved off the front of her scalp, which she found so thoroughly demoralising, that I shaved a patch of my hair off too for support. Mother offered to do it as well, at which point Father was not very calm. He said it would not be appropriate for a lady.

Cameo is just so stoic, and delights in wearing her sunglasses, joking when she goes upstairs to bed that she’s just off for twenty winks. She has done an amazing drawing of a cat that lives in the dustbin. Here we call him Guido, but next door he is called something else. No one could believe the artist was a little injured girl of five. We are all very proud.

But I’m in the dog house over the doll’s house. I didn’t intend any harm. I merely wanted to see how the lights worked, so on Boxing Day I stripped them all out. I didn’t get the chance to put it back together again before Mother came in and found me. Cameo was understanding, but to be quite honest she couldn’t

see

what I’d done. Mother’s rage was as bad as when I bent the cutlery to make up a tool kit.

As penance I had to clean out the flies from Father’s collection of Toby Jugs. He’s very passionate about his Jugs, and boasts a Martha Gunn and a Thin Man among his twenty-five pieces, dating from 1760! The original Toby Jugs were modelled on a notorious drinker of the time, Henry Elwes, also known as Toby Fillpot, so sometimes the Jugs are called Fillpots too. Father’s in love with this period in history and knows all the old songs. While I cleaned them he taught me the words of ‘Oh Good Ale thou art my darling’, which I can’t get off the brain. But anyway that means he can’t be that angry with me about the doll’s house, which is a relief. To be shut out of his study is the worst penance I know.

Best Christmas Present

New doll named Karis who says ‘Mama’. Her voice is created by a balloon and two ceramic bars in her torso, which, when squeezed, press on the balloon, forcing the air out and into the sound of ‘Mama’. A slight reshaping and weighting of the bars makes the air come out sounding like ‘pee pee’. I’m going to re-set it for Cameo because it makes her laugh so much.

Local news

Aurthur Longquist, a diminutive local boy, has chanced upon a supply of Liptons and has taken to the marketing and sale of the bags from the premises of his bicycle. Naturally we bought some, in the knowledge of his family’s need. But the irony is not wasted on me, as Father owns half of Ceylon, and that tea probably travelled here on one of our ships. We also turn a blind eye to Longquist door-stepping some of our milk. Father says in whatever way, we must do what we can for the poor, and it will save him from waiting in line for the government hand outs. I suspect Aurthur thinks that being privileged also means we can’t count.

Sue

Weds 25 February

I

RECOVERED ENOUGH

to go back to the Toastie on Monday, but what I didn’t know was that while I was ill Loudolle had been standing in for me, and it turns out that with Loudolle on the toaster there had been a steady swell in the gentlemen breakfasting. And as a good salary is Loudolle’s raisin d’être, and increased turnover at the Toastie is Mrs Fry’s, I was immediately consigned to the back kitchen for the remainder of the holidays.

Mrs Fry positively fawns over Loudolle, and says she is a little gold-mind. And wherever Loudolle goes, Icarus’s eyes follow. But it is a small comfort for me to know that at least

I

have his eye under my pillow.

I have also realised why Delia is so straps for cash – because Loudolle goes to a finishing school in Alpen. She’s developed an American accent, which considering she grew up in Ealing and spent one term at college, is really silly. I’ve known people who spend

years

abroad and still sound as English as Billy O. Everything about Loudolle involves a finish, even her name – after all she was born a Lucinda. By the time she has finished finishing there’ll be nothing left of the original.

The reshuffle at the Toastie, and the solitary hours that have become mine in the back kitchen, have allowed me too much time to reflect on the loss of mum. As I stood and buttered an army of sandwiches this morning, I recollected the moment it happened.

I was with some friends at the bus stop at the time Mum died, we were watching the rollerskating. The funny thing was that I did have a strange feeling, for I suddenly craved, for no good reason, a particular kind of sugar that Mum liked, which was out of all congruaty. By the time I got back home from the bus stop and Dad got back from his ‘conference’ with Ivana, the police were at our house.

The GP, Doctor Louden, asked if there were any other suicides in the family, as if it were somehow hereditary and not an act of despair. I explained that it was a freak act of despair, but the Doctor said that sometimes suicide’s not an act of despair, sometimes it’s an act of revenge.

‘Sue,’ said Joe’s voice suddenly. ‘Let me help you.’

He put his arm round my shoulder, and gently offered his hanky, because although my hands were still moving over the bread, I hadn’t noticed I had sodden the sandwiches. I had forgotten I was in the Toastie at all. I had regressed to an earlier time.