Campari for Breakfast (5 page)

Sue

Tuesday 3 February 1987

F

EBRUARY IS A MONTH

that is all about the promise of the year to come, about the buds that haven’t opened yet, poking their tiny shoots out of the ground.

At the Toastie, Joe and I are getting along, which is intriguing as I’d thought that I was going to get along with Nina Scrafferton, but it turns out she is a closed-in sort of a girl and not a ‘woman’s woman’. Perhaps she sees me as competition because she likes Icarus as well. You can tell because she simply thrives when he talks to her, and indulges all his jokes, then when he leaves the room it’s as if she suddenly ceases to exist. I understand the syndrome because I feel it too. One look from Icarus can keep me thriving for days.

In an attempt to drum up business, we all came into work in fancy dress for Mrs Fry’s birthday last week and she took a photo of the Toastie personnel and gave us all a copy. So I got my hands on a picture of Icarus, even if he was mostly obscured by his mother’s horns. I put the photo up on the wall in the Grey Room, just level with my eye line as I was lying in bed, so Icarus’s face would be the last thing I saw when I went to sleep at night and the first thing I saw in the morning. Aunt Coral raised an eyebrow at it, because the photo predominantly features Mrs Fry in a tarty costume, but if you look twice you can just see Icarus’s right eye.

I have spent many an hour gazing in that eye and so it is a hundred per cent distressing when Icarus is offish with me at the café. He isn’t a man of many words, but I’m afraid this only adds to his allure. I have been nearly a month at the Toastie and I can’t tell if my feelings are reciprocal, but I live in all the agonies of hope that they are.

As I have said, Joe is the opposite of Icarus and always chats to me, as long as Mrs Fry isn’t looking. For some reason unknown to herself she does not approve of her boys fraternising.

‘What sort of things are you into?’ Joe asked me one morning last week, while he was on the frother.

‘I’m into writing,’ I said.

‘No way,’ he said, ‘because that coincides with me being into reading.’ He is an interesting boy, but quite square and with a collection of earnest shirts.

After hours, I have been working hard on stories for my leading characters, the protagonists for my book: Cara, Pretafer, Fiona and Keeper. Cara is a skinny, simple farm girl and Pretafer is a beautiful seventeenth-century heiress and Cara’s nemecyst. Fiona is Cara’s servant friend, who is forced to dress in weeds, and Keeper is Cara’s spaniel.

Wednesday 11 February

Something I so wanted to happen has finally happened. And something I didn’t want to happen at all has also happened.

Today, being a Wednesday, was the last day of my week at the Toastie. It was getting on for 10.00am, and I was expecting to finish my work and go back to Green Place as usual, and settle down to some writing.

‘Are your Mum and Dad coming down to visit you at all?’ asked Joe as we toiled with the toast, the froth and the steam.

‘No,’ I said. ‘Dad doesn’t like to leave the house at Titford, and my Mum is . . . not alive any more.’

I deliberately didn’t use the ‘D’ word – I don’t like it much anyway, but also I knew it would come as a shock to a boy still blessed enough to have his mother just along the counter.

‘I’m so sorry,’ said Joe. ‘Whe— when did she pass away?’

‘September,’ I said.

He squeezed my hand on top of the toaster. ‘I lost my Dad when I was ten, I understand what you must be going through.’

‘I’m so sorry,’ I said, and then there was a pause. Joe seemed unsure what else to say.

‘What happened?’ he continued unexpectedly. ‘Was she very ill?’

‘No, she committed suicide,’ I said.

Poor Joe was so shocked that for a minute every cappuchino went cold and every slice of toast went hard and everything was still.

In real life though, nothing ceases, except your loved one. You struggle on and nothing stops for a moment. Life inside you has changed for ever, but life outside goes on the same as before, and you have to go on living with that riddle every single day.

‘Do you need to go home?’ asked Joe then, looking grave.

‘No I’m fine,’ I said, ‘but let’s not talk about it now.’

He squeezed my hand again over the toaster and then changed his tack. ‘Sandy’s having a party on Saturday night,’ he said. ‘I was wondering if you fancied coming?’

‘What a shame, I can’t,’ I said, ‘my Dad is coming over.’ Then I realised that I’d only just told him my dad didn’t like leaving the house, but it was out of my mouth before my editor was on to it. I just knew I couldn’t risk saying yes to Joe and possibly spoiling my chances with Icarus.

‘Oh, right,’ said Joe, and he smiled before getting badly distracted by some froth.

Back in Titford, if someone like Joe had asked me out I would have jumped at the chance, but Icarus has changed all that in just three and a half short weeks, and without barely a word. But, as they say in the classics, the language of love is speechless. How he can say so much to me, without saying anything at all, is a bewitching justaposition.

It was therefore some sort of miracle when, half an hour later, as I was in the kitchen buttering up the bread as usual, Icarus walked up behind me and said: ‘My brother Sandy is having a party on Saturday night, Sue, I was wondering if you fancied coming?’ The temperature in the kitchen rocketed and my knees knocked together. I held on to the counter without turning to face him because of my runaway cheeks. It was the most he had ever said to me. More than a word, more than a sentence, and

so

much more than a question. This was life, and it

can

suddenly happen.

‘I’d love to,’ I said, perhaps too willingly.

‘Great,’ he said. ‘See you Saturday, 6.30 till midnight,’ and he handed me a napkin with the address of a bar on it, and within a nanasecond he was gone. It said: ‘Saturday 14

th

Feb, Sandy’s birthday at Christine’s’. The 14

th

of Feb! That’s Valentine’s Day! Asking me out in the first place is a sure sign that Icarus likes me, but asking me out on

Valentine’s Day

, is just

so bold

. I feel so giddy that I could run through a fountain with my clothes on!

As I walked home from the Toastie, every tree, every flower, even the seeds in the earth were singing my name. ‘Sue Bowl,’ they sang, ‘Look there goes Sue’, and all the builders wolf whistled. The February buds thrust their way up through the soil, threatening every minute to burst into flower under a sky as radiant as the sun. There was only one small problem. What would I say to Joe?

Back home I went straight to my wardrobe and flung open the door. Pinafores, pinafores, nothing but pinafores. It is just my luck to be in a pinafore phase with a date with Icarus Fry in the diary. I began to feel the strong temptation to blow all my savings on a devastating dress, but I lay on my bed in the Grey Room instead and gazed into his eye. I could have stayed like that for ever, but then I heard the Admiral calling me.

‘Sue, Sue, it’s your father on the phone.’

I ran down to the hall and took up the receiver, still in heavy thought about love’s sudden beginnings. I could hear Ivana’s heels in the background clacking on the floor, yet another in the catalogue of complaints I have against that awful woman.

‘Hi darling.’ Dad’s voice was clear and familiar. ‘How are you?’

‘Great,’ I said.

‘Good, listen darling, Ivana and I are coming through on Saturday to take you out for dinner.’

In Keeper’s Care

A SKETCH

By Sue Bowl

Cara fell to her knees and cradled her Keeper to her. He howled at the moon as she cried out in sorrow and steeped his damp fur with her tears.

‘What is this whimsy!’ she screamed with abominable confusion.

And though the night was dark and starless, Keeper kept the shadows at bay. Not afar off in the pantry below, the maid was still in labour.

‘Fuck me!’ said Fiona, ‘I ain’t never bin so fuckin’ tired in me ’ole fuckin’ life.’

Friday 13 February

I had a dream last night that made me red, for the dream starred Icarus Fry. After my concerns over the double booking, it was a relief to wake from a dream which I believe to be erotic. In my dream, I was sitting, almost lying, in a basket which was attached to the handlebars of Icarus’s bicycle. We were freewheeling down a country road and for dream reasons, Icarus was dressed as a Frenchman, with berret and stripy T-shirt, and his bicycle had strings of onions around the frames of the wheels. We rolled at speed past dream pastures, sparkling brooks, random sheep, he with his legs out, abandoned from the pedals, and I delicately balanced across the basket, in a floaty dress with my legs off to the side, and light as a feather. But we whizzed down the lane so fast that we crash-landed in a heap in a meadow. Unfortunately at that point I woke up.

After recovering for some minutes I got myself dressed and went down to breakfast. When I had finished, Aunt Coral sent me up to her bathroom to fetch a cotton tip for her ear, I think in a helpful attempt to distract me from my worries about the double-booking. It was the first time that I had been in her suite alone and I couldn’t help but have a little look. There were some specialist pieces of furniture in there, including a highboy and a lowboy. The highboy is a chest upon a chest, and the lowboy is Aunt C’s dressing table. There’s also a Robert Manwaring chair which is inlaid with her favourite satinwood. Aunt C told me he was a competitor of Mr Chippendale, and a fan of the Five Orders of Architecture. (NB, I looked this up,

The Five Orders of Architecture

is one of the most successful architectural text books of all time. It was written in 1562 by Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola who was an assistant to Michelangelo and was a surprising hit as it’s full of drawings and doesn’t contain any text.)

Her bed cover is of quilted pink satin with tassels of olive and gold, and over the beheaded hangs a monogrammed panel with the letters ‘C E G’ on it. The pillows have a monogram too, but bear the initials ‘B R G’ (Mum). It made me catch my breath, because of course she was not just my mother, Aunt Coral has lost a dear sister too. I tend to forget sometimes, because in life they were somewhat distant due to their ages. Aunt C had already left home by the time my mother was born.

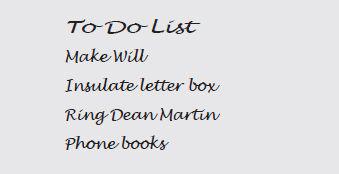

There was an old wooden desk in the window, sewn with papers. A typewriter, with Mr O’Carroll’s book open next to it, stood in the centre of the desk. The notes beside it were a mad dog’s breakfast of changes and crossings out. I also saw a To Do list sitting on her diary which read:

I must admit that the thought of Aunt Coral dying caused me to waver in myself. She is my saviour and there is little on earth as magic as her devotion. She also makes me feel like the most fascinating person ever born – she even remarks on my handwriting, eulogising the way I form my ‘y’s and ‘g’s, noticing my specialist swish under the line and back up through the side of the letter to create my trademark Spanish ovals. By the time she finishes noticing things, I feel like a million dollars, as though I could build a career around my ‘y’s and ‘g’s alone.

To shake myself out of any morbid thoughts of the loss of her, I went into her bathroom to find her cotton buds. There’s a commode in there made by the Brothers Adam for the Countess of Derby. It’s not plumbed into the mains but does as well for a fancy flower pot. I opened up her font, (the name she uses for her cabinet), and there along with all the usual digestive aids and private creams you’d expect for a woman of her age, I discovered the secret to her dazzling hair in boxes of specialist hair colour. No. 353, Arctic Silver Vixen. On the box was a picture of a foxy old lady stopping traffic on her scooter. It was such an intimate insight into Aunt Coral’s private thoughts that my heart broke for her. But unlike the lady on the box, whose hair was cut in a jazzy bob, Aunt Coral’s lightning locks are tidied in a bun which is often held up by a pencil, because she is mostly at a loss for a hair grip.

When I delivered the cotton tip she was on her own in the conservatory revising for that evening’s group.

‘Thank you,’ she said, as she relieved the pressure in her ear. She put the cotton tip in a clean tissue and clipped it inside her handbag, and ran her hands round the bottom of her chin as though she was stroking a beard. She seemed to want to express something, something that was visibly difficult, but before she could say anything we were interrupted by the arrival of group members. She took up her notes at once, her action one of the utter professional, but her expression was a hundred stories. I must remember to ask her what’s on her mind.