Campari for Breakfast (31 page)

It lasted for many exceptional minutes and then it turned to an embrace that fell amongst cushions and we passed a magnificent hour. No one has ever kissed me in the way that Joe did. He kissed me as though it was urgent, as though, if he didn’t kiss me for a good long time, he might have to have a cold bath. And, for the time that he was kissing me, all anxiety ceased.

All this time I have waited, wondered what it would be like,

who

would it be,

where

we would be, and

what

I might be wearing . . . A white dress, in the long grass, on a beach, or a hammock by a river? But I haven’t been able to see the face of the man kissing me until now. I want to go back and tell the child dreaming in the Titford bedroom, that it will be Joe Fry, in a pinafore, in the drawing room at Green Place.

‘I love being with you,’ said Joe, when we eventually paused what felt like very much later on.

‘The best things in life are worth waiting for.’

The wind outside dropped and as it did the climbers tapped softly on the windows.

‘We must make up for lost time,’ he said, which led to a temperature tremble in my body.

There were no bells or birds as had been forecast, but the sense of being desirable and treasured and feminine. It was like all the money in the universe flew to my account at the love bank, and I had gone from an account in deficit, to a gold account with cards.

The morning moon was so bright and clear it looked like it had been cut in two with a scalpel. I thought it could make a good book title,

December Moon

by Susan Bowl. It would be about a gypsy.

I was amazed that I still had room for creativity in the presence of love. But these sorts of things are not as linear as I thought, but flatter each other enormously.

The remaining moments of the night sped by carried on shooting stars, showering me in a dawn of ice diamonds, shimmering in the early light. The frost in the air was frostier and the sky a ridiculous blue. Those hours will be forever lodged safe inside my memory, and if I live to be a Nana, they will flash into my mind, like welcome visitors from that winter in my youth.

I wonder if anyone will be able to notice anything different about me tomorrow?

Brackencliffe

By Sue Bowl

And in the fine fields of Sage and Parsley, Cara had many fold ad mirers, chief among whom was a simple peasant called Philip. When Philip first kissed her, her girlhood finally came to fruition, exploding into radiant womanhood at the touch of his workaday hand. From the date of that kiss Cara’s loveliness knew no bounds, and even the men in the field sang a song of her, with her skin as fresh as the snowdrops, and her voice as soft as the day, and her love as sweet as the cider to wash a man’s care away!

With such an ad mirer as Philip, Van Day fell from a top his high horse, and Cara looked back on her childhood and thought in her maiden’s way, that if her life were a tree with bare branches, who wanted for interesting landings, ’twas in looking back that she realised, her branches weren’t bare very long.

Wednesday 23 December

At about 6.54am I woke from a fleeting dream where I was a southern belle running down a staircase, and a swooney beau was waiting at the bottom to meet me. I should say for the record that it definitely wasn’t Icarus!

When we got into work at the Toastie, Mrs Fry didn’t twig me and Joe. Her antenna must’ve been rusty, for we each had terrible helmet rings, which can take a couple of hours to plump out. And I felt euphoric about the silliest thing, such as the light bouncing on a teaspoon.

But Michael rumbled me in the toilets while we were both brushing our hair. She’d changed hers to packet dye chocolate-brown, because she was seeing someone new.

Back in the canteen Mrs Fry was busy making up new names for the coffees when we joined her. Her bracelets jangled over her jotter.

‘Café La La, Café Clever, Café Scrumptious …’

‘Café Amore?’ said Michael, with a wink.

Joe dropped me back at Green Place later on. A storm was gathering its disciples, but Joe couldn’t stay as he had a family dinner.

‘I’m so sorry I’ve got to leave you here alone. I’d be much happier if you had company,’ he said.

‘But I have got company; there’s my visitor.’

Joe had to concede he’d been out-clevered.

There’d been communication from the tramp, in that the card that I’d left him had vanished. Upstairs the locked-room light was switched on again.

I was just about to baton down the hatches for one of my famous nights in, as daggers of sleet started to rage warfare over the holidays, when I looked out of the window and saw someone in the distance flickering a powerful torch. Its bright shaft shone out over hills and the roads, picking up rain in its tunnel of light like fine just-visible pins, illuminating the tarmac with a vicious sheen of water. The plumes of buddleia caught in its beam were still hanging just as they had been in the summer, exactly the same shape, but now brown, as if they’d been smoked. And their scent was no longer of lilac but of tobacco. I opened the window so I could smell them.

But what a sight awaited me: the light flashing up the drive appeared to be Joe on his way back. And there was someone on the back of his bike, sitting side saddle in a skirt. The sight of her bird legs dandling off the edge – I know I will never forget it. Her cold, thin face was full of concern and urgency when they stepped inside.

‘What are you doing here?’ I said.

‘I was unable to get a taxi,’ said Aunt Coral.

‘I was passing the station and I spotted her waiting in the rain,’ Joe said.

‘Yes, it was blessed, thank you Joe,’ said Aunt C.

‘But where are all your things. Delia, and the Admiral?’ I asked her.

‘I needed to come back without delay. There’s something we need to look at. I don’t mean to be cryptic; it’ll be easier if I show you.’

And without taking her coat off she went into the drawing room.

‘The house looks good,’ she said absent-mindedly, dripping rain all over the floor.

She looked through her important papers, which I had been keeping under heavy covers for her, and drew out the log book of Mrs Morris, the old housekeeper. She turned over a few pages before presenting it to me.

‘I don’t know why I didn’t think of it until this evening,’ she said. ‘I’m so sorry I’ve been so slow. But better late than never. I wanted to get here as soon as I possibly could.’

We ran up to the Grey Room like two crazed surveyors. There

was

a loose floorboard, and there

was

a key underneath it. I’d always thought it was odd she should leave it in Titford, right in Red Indian Territory.

I took it up in my hands, as if it were her precious ashes. Here lay the answer surely, in the shape of a small brass key.

‘When did she last come here?’ I asked, with the growing awareness that this must have meant she had planned her death for some time.

‘She came for the funeral, and once more in September,’ said Aunt C.

‘Didn’t you ask her why she’d come?’ I said.

‘I wasn’t here,’ she said.

‘I feel sick.’

When I returned from the loo, Aunt Coral was on the telephone calling through to the Egham Fleet. It took twenty minutes for a taxi to come because it was busy season; I was going to start walking had it taken a moment longer.

The lockers at Titford station are par-owned by the leisure centre, impersonal metal boxes, used mostly for sweaty clothes. Our car drew up into the warm clouds of exhaust that hang at the side of the concourse, filling our noses with the fumes. There were doors clunking, warmth inside cars, and people heading home for Christmas.

But once we were inside the station, I doubted if ever the platform had been walked for such a grim purpose. The ground was polished and cream under foot, and Aunt Coral held my hand. It was the same floor that Aileen and I used to slide along in our socks if we happened to be taken out with a grown-up to meet friends coming in on the train.

Dread and excitement filled my heart when we stopped at 402. It was almost like going to see her. The door was black as a coffin, and the little white number was chipped. We hesitated for a moment, uncertain if it was the right one.

Aunt C looked at me and gently tried to take the key from my fingers.

‘No, I want to,’ I said.

With a shaking hand, I opened the door, to be met with the sight of two quite plain shoeboxes. I don’t know what I was expecting – guns, perhaps, or a sawn-off head – but the contents seemed much too ordinary in relation to my expectations. I’d imagined stolen money, or drugs, or bloodstained clothes, something fantastic, but not inanimate boxes.

I drew them out, and we returned to the Titford rank. The sound of our steps on the platform was like a solemn military band. I carried my grave treasure tight in my arms like a baby. Aunt Coral had brought her shopping basket, in case we should need a container, but I didn’t put the shoeboxes in, so she carried it along quite empty.

Unfortunately, the next cabbie was a chatterer. Aunt C made valiant conversation, the effort of which she signalled to me via secret squeezes. He went on about the road works on the bypass, and told her he was a Santa in the department store but they wouldn’t give him a grotto.

‘They only provide an elf,’ he said.

Even at such moments as these, it seems there is no time for silence. Although, God bless him, how was he to know?

The moon broke through the night sky like a torch suddenly illuminating the floor of the car, searching the top of my boxes with sad, silver light. The same moon that shone for me and Joe, the same moon that silently watches everything.

Back at Green Place, I went straight into the drawing room, with my hat and coat still on, and Aunt Coral sat in the window. I tipped the contents of the boxes out on the floor. I was shot with adrenalin head to toe; the blood of courage.

She had left me a savings account with her rainy day fund, ten thousand pounds in all. And there were old birthday cards and baby photos, and the things from her empty ‘Blue’ folder. Some snippets she’d made into a collage, with some pictures she liked, her eyelashes from the sixties, and ribbons from her bouquets. A life can boil down to two shoeboxes it seems; to remembered birthdays and holidays. Her life was short, but now it also seemed small.

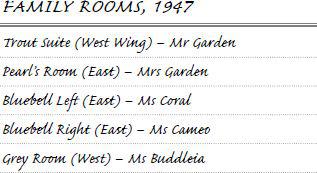

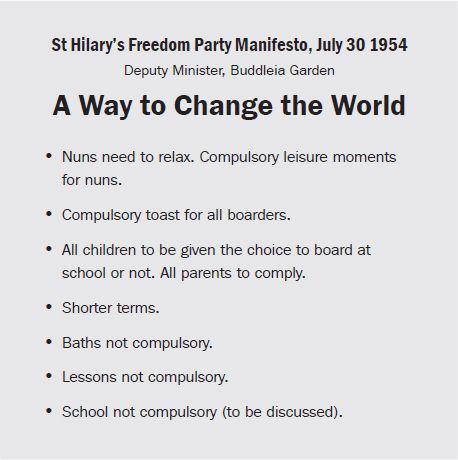

Odd pages from her schooldays lay scattered on the floor like confetti. There were pages from her days at St Hilary’s, a rambling kind of poem, and something that was addressed to Aunt Coral.

Kitchen Novelty competition, St Hilary’s 1962

Buddleia Garden’s Entry:

ROSE PETAL WINE

Here is a family recipe, inadvertently discovered by my sister.

For the infusion:

Sugar

Champagne yeast (never use bread yeast, it tastes foul)

Cooled boiled water

Method:

1

Activate the yeast by adding sugar and warm water in a bowl. Let it sit for ten minutes.

2

Mix together with the rose petals, add more water to taste.

3

Pour into bottle with scrunched sock in the top.

NB this must allow AIR as fermentation can cause EXPLOSION.

‘My father’ (A poem by BG)

July 15 1986

Who are you?

An emperor, or a king? If I saw you in a café, would I know you? Would I have the nerve to tap you on the shoulder and ask, ‘Are you my Dad?’

To Coral,

The truth has finally made sense of why I have always felt like an outsider, of why I was sent away to school, of all that has been missing.