Campari for Breakfast (29 page)

‘We came as soon as we could,’ said Georgette. It seemed they had come on a mission.

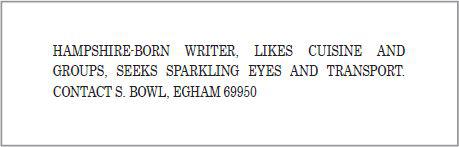

‘You see we were catching up with the papers,’ said Print, ‘and we would not have put two and two together had I not had a visit from an old friend. She was in the area for a bowels match and she spotted your advertisement.’

‘I’m sorry, I don’t follow,’ I said, confused by the Nanas’ ramblings.

‘Her name is Emily Laine,’ said Print, ‘and Emily is Jack Laine’s widow.’

It wasn’t long before they were back on their favourite subject, (the Duke of Edinburgh), but all I could think of was Emily Laine amidst the talk of the Duke’s plus fours. They stayed for an hour or so before returning to the home, and their taxi had barely pulled away before I telephoned Aunt Coral.

‘Are you going to contact Emily Laine?’ I asked her, once I’d filled her in.

‘I don’t see how I can,’ said Aunt Coral. ‘What if she doesn’t know about it?’

‘Maybe you could get Print to try and find out if she knew?’

‘No, Print knows nothing about Jack and Cameo and I’d have to tell her, and she’d feel awful for Emily. No, dear me, I’ll have to think about it.’

I also told her about the man I’d seen, and the coat.

‘Are you sure it was a man? Are you sure it wasn’t a ghoul?’ she asked.

I found this quite unsettling – that she would rather believe in a ghoul than a man! Seems to me she’ll believe whatever is most reassuring. She’s a Caroline through and through.

I am sitting up in the Grey Room again, trying to commune with mum and prepare myself for later, when Joe is taking me to Titford.

In the early evening Joe came for me on his bike, as promised. It was the first time I’d ridden pillion, and a moment I was not unaware of.

It took us only 45 minutes to get there – it takes an hour and a half on the train. But it feels a lifetime away from Green Place and the Egham borders.

Once inside, I slipped straight upstairs to retrieve the key as per the instructions on Mum’s note.

‘I wish my Dad had left me something like this,’ said Joe, of his own distant grief.

‘I’m so sorry, sometimes I forget that you’ve lost your Dad.’

‘It’s all right, I’m over it now, I’ve grown up,’ he said, trying to be jolly and manly. ‘So it’s a key to a locker your mum has left you in secret? Goodness me.’

‘It’s under a floorboard that only she and I know about,’ I said.

‘Wow,’ he said, closely following me upstairs.

Dad and Ivana’s bedroom smelled like the foyer in a department store, and there was flat champagne in the tooth mug.

I lifted the board up gently, looking down into the hole underneath it as though I were looking down a precipice from which I was about to fall off.

‘Joe,’ I said.

‘What is it?’

‘There’s no key.’

Coral’s Commonplace: Volume 4

Green Place, Dec 2 1962

(Age 40)

I’m off the botanist again; much more off than on lately in fact. Daphne is convinced it’s because he finally proposed, and that if he hadn’t, I would be much keener. The minute I’ve got him, I don’t want him and the minute I haven’t, I do.

For all these years, when it comes to romance, I had thought that I was quite traditional. But it turns out that I just can’t breathe when I feel tied. And Edgar is so very similar to me; like a cosmic reflection. But am I spoiled? Am I ill? Am I greedy, to wonder if the grass may yet be greener? Am I to stay a child, when all my friends have grown up?

As I look out of the window, I can see clouds of smoke from a bonfire. The window pane is misted up, apart from one central patch that’s been blown clear by the new morning. And on the other side of the window, we are totally enmeshed in webbing. Maybe it’s the spiders that have held this dear house up so long. Each frail fingerprint sparkles like fibreglass. It’s as though they have cast their nets in the air and captured the entire house.

There’s an island off the coast of Madeira they call Spider Island, which apparently is inhabited ONLY by spiders as big as the average boy’s hand. I’d love to go and see them, but who would dare to come with me? Edgar would’ve enjoyed it, but there’s no point in thinking about that . . . Still, at least we only had plans for bonfire night this time and not for the rest of our lives.

He wrote me a pompous letter about his various reasons for ending it, it was written with a third eye over it, in case his biographer ever gets hold of it. He’s moving to Hampshire with a woman with a pronounced widow’s peak. But if I am forlorn I remind myself that I could never see myself doing his dishes, or feeding his ravening guests, or walking from his bathroom to his bedroom dressed in his flannel pyjamas. I could never live in a flat, and I don’t ever want to leave Father. It’s not hard to imagine why Edgar decided to call it a day!

My friends it seems are happier with my being alone. Daphne prefers me to retain what she calls my ‘mad Aunt’ status, because it makes the toil of motherhood seem so stable and reassuring. ‘Aunt’; the word conjures to me a tweedy, lonely figure or, God forbid, a type of Miss Havisham. No, if Buddleia ever makes me an Aunt I will not take after Miss H. I am not going to pine over Edgar. Broken hearts do mend, and anyway, one daughter lost too young is quite enough for Father. It struck me last night as I lay in bed, in profound talks with the ceiling, that Cameo lived life so quickly. Maybe she had a notion she had better grow up double fast. Our lives seem like waves, some that will go the distance of all the oceans, and some that will lap gently two or three times before heading straight for the shore.

Talking of which, I am trying to persuade Father, who is now sixty-four, to come away with me for a day or two’s break to the seaside, just to get him out of the house, as he is in such bad shape at the moment. But he said he can’t in December, because he has an ‘appointment’. ‘December’s a write-off,’ he says. He’s a curmudgeon, a hermit, and extremely bad tempered. And I wonder if I live to be old, will I start to shuffle too?

Oh, and Buddleia’s won a novelty prize at school. I wonder what it was for!

Sue

Sunday 6 December

I

T HAS STRUCK

me that finding a rambler in a trespasser trap holds huge potential for falling in love, so I have put a little notice in each, in case someone lovely should chance to fall down one. Can you tell I am losing hope of Icarus? Love is blind; but love is also impatient.

It is the dankest day of the year. All the buckets are out to keep the rain off the carpets, and I have removed the conservatory furniture, for the sky is threatening to come in. It is lucky I have had this to distract me from despair over not finding that key.

We couldn’t find it anywhere in the house, so we drove back to Egham empty-handed. Later I rang Aunt Coral, and she was as confused as me.

‘Could your Father have found it?’ she asked me.

‘I’m sure he didn’t know about the floorboard. And Ivana wouldn’t be bothering with the floor because they have a cleaner,’ I said.

‘I’m so sorry Sue. Perhaps you’ll just have to ask him if he’s got it?’

‘But what if he hasn’t? Mum said that she didn’t want him to know.’

‘I know. It’s a mystery. I’ll need to have a think, try not to worry, I’m sure it will turn up,’ she said, trying her best to rescue.

She also told me by way of distraction that she has formed a salon in Knightsbridge that is sitting

every

evening. It’s clear that she and her entourage are getting very serious about Group. And as the gala is galloping up, Aunt Coral has called an EHG for next Friday, to be held at the flat in London, with all the hirsutists travelling from the four corners of the earth. (Well, Egham, London and Alpen.)

Friday 18 December

Egham Hirsute Group in the Capital

Joe and I took the train together and he kept both our tickets in his wallet like a true gent. Over the tannoy the guard said: ‘Please ensure you have all your personal longings with you when you leave the train.’ I wonder if he knew just how accurate he was in his little mistake.

It was a much larger Group than expected, with Daphne and Mrs Stock Ferrell and her Labrador Daniel, and the Admirals G and T with their friend Admiral Ranger, and Admiral Little, Joe and me, plus George Buchanan, a dentist. The Admirals sat according to rank, out of respect for Admiral Ranger. Delia was fresh back from the airport, and rather heavier than usual. As a consequence, she’d glued a picture on her pad of a thin woman smiling at some berries. There was a fire going in the hearth, and we each had a Knightsbridge cushion.

‘Welcome, welcome,

welcome

, to the Metropolis EHG!’ said Aunt Coral, and the Admirals raised their pencils like a row of tiny cannons.

‘Let’s start with a warm-up,’ she said, as the Admiral poured her a Sapphire. ‘Now, quick fire, who can tell me another word that means the same as style?’

We all put our hands up.

‘Sue,’ she said.

‘Panache.’

‘Excellent, yes, and Avery?’

‘Flair.’

‘Excellent, yes, and George?’

‘Chic.’

‘Excellent, Admiral Ranger?’

‘Fence,’ he said.

‘Jolly good, yes, it also means a type of fence,’ she said, moving quickly to the next exercise in her notepad. ‘Now, could I have someone to kick off with a sentence from their story? And if you haven’t written a story, don’t worry, you’ll still be able to follow the exercise.’

We all put our hands up.

‘Sue,’ said Aunt Coral, and I read aloud from ‘Brackencliffe’, hoping I hadn’t shown how much I had wanted to read.

‘“My name is Knight Van Day,” he said, “and I come from wither and yonder.”’

‘Thank you, Sue. And who’d like to have a go at expressing what Knight Van Day says in a different way? Avery?’

‘“I am Knight Van Day,” said the Admiral, “and I get around.”’

‘Excellent, Avery, yes. And George?’

‘“My name is Knight Van Day and I’m not telling you where I live.”’

‘Good George, well done – a completely different take on the same edit. Excellent, and Admiral Ranger?’

‘“My name is Knight Van Day, that’s my house over there.”’

‘Thank you Admiral Ranger, very good.’

Aunt C definitely has her ways of making the gentlemen feel very special about themselves. George, Admiral Little and Admiral Ranger were what I can only describe as glowing, even if their edits of my line were completely off of the mark. She seemed oblivious to the ladies, other than myself, who had their hands up too. It’s like she has a sort of lady blindness, or at least a dominant eye for the gents!

‘Now, it seems to me,’ she said, moving Group forward, ‘that the majority of us are of an age where childhood wasn’t yesterday. I only mention this because I want us to think about time. If I might use my own life as an example,’ she said, reading aloud from her notepad:

‘The air looks different in the past. When I watch back my old reel-to-reels it’s as though the air is thicker, mellower, sweeter, the sky is pale and warm. Or is it that I imbue the past with a misty significance? A honey haze that didn’t exist at the time? For I’m sure the air was exactly the same then, perhaps, but for less deodorant.’

She paused to allow Group to laugh and appreciate her wit.

‘I expect all of us would like to be able to take what has happened in the past and change it to make something different happen. But we can write ourselves a

future

, and we can even try and make it happen. So, I’d like you to write a short piece and mess around with your time frame. You might wish to write about the past, or you might set yourselves in the future, and if you do, what will you be doing, and who will you be?’