Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (50 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

Our time in a particular job, or in a role, can be seen as a lifetime. We are born when we get a job and we die when we leave that job. In every job, there is a learning phase and a productive phase, and eventually a time to move on. In between there is boredom and frustration. The monotony of the job gets to us. The executive wants to be manager and the manager wants to be director.

This is when it is time to retire. We seek new opportunities, different opportunities or greater responsibilities, either in the same organization or another. We seek the death of our current job and rebirth in another. In other words, we seek growth.

But to grow into the next job, we have to create talent from someone downstream who will replace us and make ourselves available to someone upstream, who by helping us grow enables us to move on to the next phase of the career.

When Akhilesh became the head of a cooperative bank, he made it a rule that no one would get promoted until they spent a year as trainers developing future talent. His reason for this is two-fold: to ensure new talent is developed and to ensure the experienced executive's practical knowledge is updated with the latest academic theories. His training department exists primarily for administrative and supportive roles with the course content and direction being determined by those who are market-facing. Initially, people resisted the change because in their view a posting in training was akin to being sidelined. Now they see it as a route to higher and more powerful responsibilities. By being vanaprasthis to the next generation, they free themselves from being brahmacharis to the previous generation. By helping those downstream grow they grow in the upstream direction. Akhilesh's plan has been so successful that other banks are asking him to help them set up a similar system. It is not about creating a system: it is about giving attention to what matters.

We seek to inherit things, not thoughts

At the end of the war at Kurukshetra, as the victorious Pandavs are about to assume control of Hastinapur after vanquishing the Kauravs, Krishna advises them to talk to Bhisma, their grand uncle, who lies mortally wounded on the battlefield. As the result of a blessing, death will elude him for some time. "Make him talk until his last breath. Ask him questions. He has a lot to tell and you have a lot to learn," says Krishna.

Sure enough, when prompted, the dying Bhisma spends hours discussing various topics: history, geography, politics, economics, management, war, ethics, morality, sex, astronomy, metaphysics and philosophy. Bhisma's discourse is captured in the Shanti Parva (discussions of peace) and Anushasan Parva (discussions on discipline) that make up a quarter of the Mahabharat. After listening to their grandsire, the Pandavs have a better understanding of the world, and this makes them better kings.

The Pandavs need Krishna's prompting to seek knowledge from Bhisma. They do not need this prompting to sit on the throne or wear the crown. Like plants and animals, we are naturally drawn to Lakshmi and not Saraswati. We have not yet got used to what it means to be human. Tapping our human potential is not our top priority. We are convinced we have already realized it. Hence the focus on growing what we have rather than who we are.

Gyansingh watches in dismay as his children fight over the property and business. For years, he insisted they work with him. He wanted them to learn the tricks of the business, but they sat with him only out of a sense of duty. He sensed they did not think they had much to learn. They had their degrees from great colleges and so assumed they knew everything. All they wanted from Gyansingh was power and control. They see him as the source of Lakshmi and Durga not Saraswati.

Being a yajaman is about gaze, not skills

When Vishnu descends as Parashuram, he has three students: Bhisma, Drona and Karna. When he descends as Krishna, he gets all three killed on the battlefield of Kurukshetra, for they had failed him as students.

All three learnt the art of warfare from Parashuram and became great warriors. The purpose of all Vishnu's avatars is to establish dharma. Dharma is not about skill; it is about gaze. None of these students expanded their gaze; their gaze was focused on their own desires and anxieties and fears and hence they ended up leading the Kaurav army, much to Vishnu's dismay.

Every Brahma focuses on understanding prakriti so that he can control the outer world. Few focus on understanding purush so that they can develop their inner world. Sharda does not matter as much as Vidyalakshmi.

Since every Brahma is convinced that his gaze is perfect, he focuses on domesticating the world around him with rules. But for humans, dharma is about expanding the gaze. When the gaze expands the futility of trying to dominate those around us or domesticating them with rules is revealed.

Parmesh, the head of the training department in a public sector company, has come to the conclusion that most people see promotions as a chance to wield authority and dominate those around them. They see being bossy as a perk. They do not see promotions as enabling them to see the organization, the market and themselves differently. This belief stops them from acquiring new knowledge and skills, or paying attention to the gaze of seniors. They see training simply as a way by which the organization domesticates talent. That is why, while they court promotions, they resist coming to training programmes; they already know what they need to know. What they do not know they expect their juniors to know.

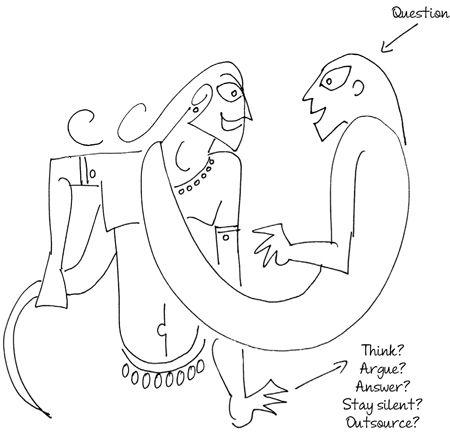

Questions teach us, not answers

Students can be classified as the five Pandavs: Yudhishtir, Bhim, Arjun, Nakul and Sahadev.

- Yudhishtir, as king, expects others to know the answers.

- Bhim, a man of strength, prefers to do rather than think.

- Arjun, as an archer, sees questions as arrows shot at him and deflects them by asking counter questions. He is not interested in the answer.

- Nakul, the handsome one, is not capable of thought.

- Sahadev is the wise one who never speaks but is constantly thinking and analyzing. When asked a question, he is provoked into thought and comes up with an intelligent answer. If not asked a question, he stays silent.

A teacher who wants to invoke Narayan in his students follows the Sahadev-method of teaching: he asks questions and does not give answers. The teacher is not obliged to know the answer. The questions are meant to provoke thought, create emotional turmoil and inspire the student to find the answer. For the answers benefit the student, no one else. If the student refuses to find the answer, it is his loss, not the teacher's.

In the

Kathasaritsagar

, Vetal makes Vikramaditya wiser by asking him questions. The crematorium where the Vetal lives is the training room, where the past is processed for wisdom that can be applied in the future. Vikramaditya has to come to the Vetal if he wishes to serve his kingdom better. He has to come and then return. If Vikramaditya chose not to go to the crematorium or answer any question, it would be his loss not the Vetal's who is already dead. The Vetal must never go to Vikramaditya's kingdom, for he will end up haunting the land of the living.

When Lydia was appointed the head of the learning and development wing, she laid down some ground rules. Trainers were told not to herd participants into training rooms: they were free to come and go as they pleased. Learning was their responsibility, not the trainers'. They were not children who had to be disciplined. There was very little instruction on the part of the trainers; there were only questions asked and participants were encouraged to answer and analyse the reasons for the answers. Case studies were prepared using the knowledge of the organization itself. Sales, marketing, production, logistics and accounts officers were video-filmed and asked to present the common problems they faced and issues they expected to resolve so that everyone could share their thoughts on these. The focus was on practical work rather than theory, active answering rather than passive listening. Lydia put up a notice at the entrance stating, "Unless you speak we are not sure if you have learned anything."

We resist advice and instructions

While King Virata of Matsya was away chasing the king of Trigarta, who had stolen his cows, the Kaurav army took advantage of his absence and attacked the city. There was no one around to defend the city except the women and children. Everyone was frightened. "Do not worry, I will protect you," said the confident young prince, Uttar.

A eunuch called Brihanalla who taught dancing to the princess warned the prince that the Kauravs were a mighty force not to be taken lightly and that no single warrior could defeat them, except maybe Arjun. Uttar did not take too kindly to this comment. He admonished Brihanalla. "Know your place in the palace," he roared. Brihanalla apologized immediately. Unfortunately for the prince, there were no charioteers left in the city. "What do I do now? How can I ride into battle without a charioteer?" he whined. Brihanalla offered him his services, claiming to have some experience in charioteering. Though not happy to have a eunuch as his charioteer, the pompous prince, armed with a bow, rode out with Brihanalla to face the Kauravs in battle, cheered on by the palace women. When Uttar entered the battlefield and saw the enemy before him, he trembled in fear. Before him were great warriors, archers and swordsmen on horses, elephants and chariots. In a panic, Uttar jumped off the chariot and began running back towards the city. The Kauravs roared with laughter, further humiliating the embarrassed prince.

The eunuch-charioteer then turned the chariot around, chased the prince, caught up with him and drove him out of the battlefield into a nearby forest where she revealed that she was no eunuch but Arjun, the great archer, in disguise. "I will not tell your father about your cowardice but you must promise not tell anyone who I really am," said Brihanalla. An awestruck Uttar agreed.

And so, Brihanalla pushed back the enemy and Uttar returned to a hero's welcome. But the prince was not carried away by the praise; he knew the truth about himself. He was grateful to Arjun for revealing to him the truth about his martial abilities, without taking away his dignity.

This story from the Virata Parva of the Mahabharat provides an important lesson in mentoring. Arjun is Uttar's mentor. Uttar imagines his capability and is ignorant about the true identity of his eunuch-charioteer until he is faced with a crisis. Arjun is mature enough not to humiliate the young, inexperienced prince, focusing instead on his growth. Students do not like being told what they can and cannot do. They need to discover it for themselves. Crisis usually helps.

When Dilip came back from business school with a business idea, his uncle Naresh agreed to fund him. "But it will not work," shouted Dilip's father, Mahesh. "I know," said Naresh, "He is young and wilful and will not listen to us. He has to figure it out himself. Besides we could be wrong. If he succeeds with the money I give him we all will benefit. If he loses, he will come back a seasoned, battle-scarred businessman."