Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (45 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

Reflection

When we genuinely see others, we realize that they are often responding to their perception of us. How they see us is very different from how we see ourselves. As we contemplate this, we understand the world and appreciate ourselves better.

Fear isolates us while imagination connects us

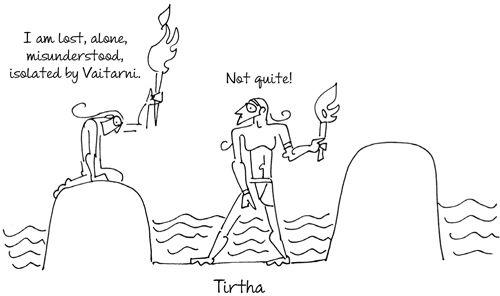

The Garud Puran refers to a river called Vaitarni, which separates the living from the dead. This is the metaphorical river of fear that surrounds every brahmanda separating it from the other brahmanda.

The word 'tirtha' refers to a ford, a shallow part of the river that allows one to cross over to the other side. Unlike a bridge that needs to be built, a ford exists naturally and has to be discovered. Imagination is the ford that enables a yajaman to explore the devata's brahmanda and even reflect on how his own brahmanda appears from the other side. Tirtha transforms Vaitarni, the river of fear that separates, into Saraswati, the river of knowledge that connects. The yajaman who discovers the tirtha and walks on it is the tirthankar. In Jain scriptures, all worthy beings are classified as:

- Those who are action-driven like the vasudev who fights the prativasudev since his pacifist brother, the baladev, refuses to.

- Those who are rule-driven or the chakravartis.

- Those who are thought-driven or the tirthankars.

The tirthankar can see that while the vasudev feels like a hero and views the prati-vasudev as villain, the prati-vasudev sees himself as a leader, the chakravarti or keeper of the universal order. For the chakravarti, the vasudev is no hero; he is a rule-breaker, a threat to order. Neither sees the other. Vaitarni isolates each one. Unless they walk over the tirtha, there will always be conflict and violence in their relationship.

For the tirthankar, the other serves as a mirror or darpan. In them, he sees reflected aspects of his own personality and his own fears. If he judges these feelings, and choices, he will deny them, indulge them, justify them, fight them, but never outgrow them. To outgrow them, he has to accept their existence and be at peace. This is non-violence.

We often see the world through our own prejudices. The realization that everyone does the same thing should prompt us to observe other people's prejudices and wonder why they feel the way they do, rather than simply dismissing them. The chakravarti is too busy finding fault in vasudev, and the vasudev too busy fighting the prati-vasudev. Should the chakravarti invest more time in wondering why vasudev looks upon him as prati-vasudev, and should the vasudev invest more time in wondering why not everyone looks at the king as the villain, both would walk the path of the tirthankar.

Urvashi started a toy business. She could see huge potential both locally and internationally, but she could not scale up her business as government policies saw it as a cottage industry. These laws were instituted to protect and encourage small players. But these laws were shortsighted and they did not stop international players from supporting their toy industry and enabling them to create products at low rates and exporting them to other markets. As cheap foreign toys flooded the market, Urvashi lost her competitive edge in the market. Urvashi begged the government to intervene and the banks to reconsider their policies. But like stern chakravartis the bureaucrats and ministers refused to budge. Urvashi sees the government as prati-vasudev, the obstacle to her chance of being a successful entrepreneur. She had to close down her business and take up a job once again.

We often forget that others see the world differently

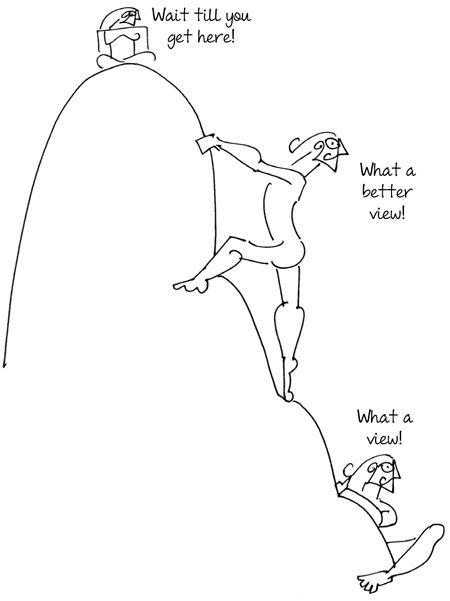

After the war at Kurukshetra, where the Pandavs defeat the Kauravs, there is an argument as to who is responsible for the victory. Is it Arjun who killed the mighty Kaurav commanders Bhisma, Jayadhrata and Karna? Or is it Bhim who killed the hundred Kaurav brothers? No one can decide, so they turn to the talking head on top of the hill overlooking the battlefield.

This is the head of a warrior who was decapitated before he entered the battlefield. He so longed to see the war that, taking pity on him, Krishna had his head put atop a hill. From this vantage point, he could see everything that happened in the battle over eighteen days.

When asked who was the greater warrior, the talking head said, "I did not see Bhim or Arjun. I did not see the Pandavs or Kauravs. I only saw Vishnu's discus severing the neck of corrupt kings and the earth-goddess stretching out her tongue to drink their blood."

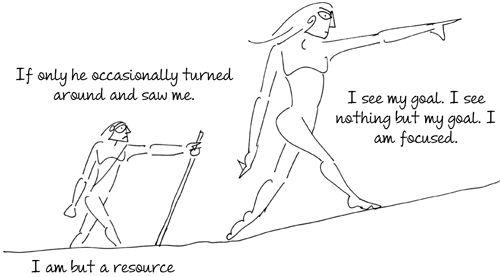

In our yearning to be seen, we assume our own importance, until someone comes along and reminds us that we are but part of the big picture. Our roles in our departments sometimes become so important that we forget that we are part of a bigger picture. Our transaction that causes us great joy or pain is merely one of the thousands of transactions that are part of our enterprise.

People who have been in line-functions or customer-facing functions resist doing desk jobs in special projects or corporate offices. This is usually a good thing in one's career, at least for a short duration. But by working for some time in the HR department or finance department or CEO's office, they get a wider view of the organization and are able to contextualize the roles of those in the frontline. Somehow, from the dizzy heights of Kailas, the frenzy in Kashi seems insignificant.

When Utpal's company made 40 per cent profits, the workers expected a 40 per cent bonus. But they received only a 10 per cent bonus, barely enough to account for inflation. The workers protested. Utpal explained he needed the profits to build another factory that would allow him to increase capacity and lower the cost of goods produced, which would enable him to stay competitive in the markets. But the workers felt this was an elaborate argument to deny them their dues. And how would they benefit from a larger factory? Utpal was thinking long-term while the workers were thinking short-term. This led to many arguments and threats of a strike. Utpal saw the workers as obstacles to his vision. He was determined to have his way and create more automation so that he would never have to deal with such labour issues.

How we see others reveals who we are

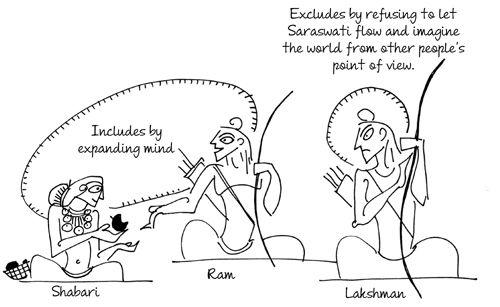

In the forest, while searching for Sita who had been abducted by Ravan, Ram and Lakshman meet an old lady called Shabari who invites them to a meal in her house. She offers them her frugal meal: berries she has collected in the forest.

Lakshman is horrified to see Shabari taking a bite of each berry before passing it on to his brother. Sometimes, she does not even pass the berry and just throws it away. "How dare you give leftover food to my brother?" Lakshman snarls. "Do you know who he is? He is Ram of the Raghu clan, king of Ayodhya!" An embarrassed Shabari throws herself at Ram's feet and apologizes for her mistake.

Ram looks at Lakshman with amazement, "What are you seeing, Lakshman? Here is a woman who is sharing the best of the food she has gathered for herself with two complete strangers, armed men at that. And you are angry with her? Look at her: she lives in the forest, and you expect her to know palace etiquette. She is biting the berries to make sure she feeds us the sweetest, most succulent ones. And instead of appreciating her generosity and kindness, you are angry with her! What does that say about you? Ayodhya and the Raghu clan may be important to you but they mean nothing to her. You expect her to see me as you see me. But do you really see me? Do you see anything except the way you imagine the world?"

The way Lakshman sees Shabari says nothing about Shabari; it reveals everything about Lakshman. The decisions, instructions and attitude of a yajaman reveal how he sees the yagna and the devata, and his own role. More often than not, a workplace is full of Lakshmans, ready to judge and instruct the Other, unlike Ram who appreciates people for who they are.

Many leaders insist that their assistant leave a small note about the background of the person they are about to meet before the meeting takes place. This ensures they do not make any blunders during the conversation and they are able to give the person they are meeting the impression that they matter, that they have been seen.

At a team meeting, the junior-most trainee proposed an idea. "That is ridiculous," snapped the chief operating officer, Qureishi. Later, during a coffee break, the chief executive officer, Ansari, took Qureishi aside and said, "By ridiculing that trainee's proposal you have frightened everyone in the team. Now they will not be free with their ideas. They will be wary of what you may say. No one wants to look foolish. Imagine the trainee was brave enough to open up in front of the top management. Instead of appreciating him, you have mocked him. Made him feel even smaller than the junior status he currently occupies in the organization. You saw his proposal objectively, I understand. I wish you had seen it subjectively. Then you would not have demotivated him." Like Lakshman, Qureishi had failed to see the courage of the trainee. Now he realized why Ansari was such a favourite with everyone in the organization. It was not just the position he held. Ansari never ridiculed anyone; he never made anyone feel small. He genuinely valued everyone's ideas and helped each one see why it could, or could not be, implemented.

How others see us reveals who we are

Surya, the sun-god, was horrified when he noticed that the woman in his house was not his wife, Saranya, but her shadow, Chhaya. He stormed to the house of his father-in-law for an explanation, only to learn that she had run away because she could not bear his celestial radiance.

Surya realized that while in his story he was the victim, according to his wife he was the villain. That she had slipped away in secret and left a duplicate behind in her place was an indicator of the extent of her fear. Had he seen the world from her point of view, he would have realized beforehand what had frightened his wife before she had taken the drastic step of running away.