Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (30 page)

Read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee Online

Authors: Dee Brown

This was why in the spring of 1871 the Commissioner of Indian Affairs so eagerly petitioned Cochise to visit Washington. Cochise, however, did not believe that anything had changed; he still could not trust any representative of the United States government. A few weeks later, after what happened to Eskiminzin and the Aravaipas at Camp Grant, Cochise was even

more positive that no Apache should ever again put his life in the hands of the treacherous Americans.

Eskiminzin and his little band of 150 followers lived along Aravaipa Creek, from which they took their name. This was north of Cochise’s stronghold, between the San Pedro River and the Galiuro Mountains. Eskiminzin was a stocky, slightly bow-legged Apache with a handsome bulldog face. He could be easygoing at times, fierce at others. One day in February, 1871, Eskiminzin walked into Camp Grant, a small post at the confluence of Aravaipa Creek and the San Pedro. He had heard that the

capitán,

Lieutenant Royal E. Whitman, was friendly, and he asked to see him.

Eskiminzin told Whitman that his people no longer had a home and could make none because the Bluecoats were always pursuing them and shooting at them for no reason other than that they were Apaches. He wanted to make peace so they could settle down and plant crops along the Aravaipa.

Whitman asked Eskiminzin why he did not go to the White Mountains where the government had set aside a reservation. “That is not our country,” the chief replied. “Neither are they our people. We are at peace with them [the Coyoteros] but never have mixed with them. Our fathers and their fathers before them have lived in these mountains and have raised corn in this valley. We are taught to make mescal,* our principal article of food, and in summer and winter here we have a never-failing supply. At the White Mountains there is none, and without it now we get sick. Some of our people have been for a short time at the White Mountains, but they are not contented, and they all say, ‘Let us go to the Aravaipa and make a final peace and never break it.’”

5

Lieutenant Whitman told Eskiminzin that he had no authority to make peace with his band, but that if they surrendered their firearms he could permit them to stay near the fort as technical prisoners of war until he received instructions from his superior officers. Eskiminzin agreed to this, and the Aravaipas

came in a few at a time to turn in their guns, some even disposing of their bows and arrows. They established a village a few miles up the creek, planted corn, and began cooking mescal. Impressed by their industry, Whitman employed them to cut hay for the camp’s cavalry horses so they could earn money to buy supplies. Neighboring ranchers also employed some of them as laborers. The experiment worked so well that by mid-March more than a hundred other Apaches, including some Pinals, had joined Eskiminzin’s people, and others were coming in almost daily.

Whitman meanwhile had written an explanation of the situation to his military superiors, requesting instructions, but late in April his inquiry was returned for resubmission on proper government forms. Uneasy because he knew that all responsibility for actions of Eskiminzin’s Apaches was his, the lieutenant kept a close watch on their movements.

On April 10 Apaches raided San Xavier, south of Tucson, stealing cattle and horses. On April 13 four Americans were killed in a raid near the San Pedro east of Tucson.

Tucson in 1871 was an oasis of three thousand gamblers, saloon-keepers, traders, freighters, miners, and a few contractors who had made fortunes during the Civil War and were hopeful of continuing their profits with an Indian war. This backwash of citizens had organized a Committee of Public Safety to protect themselves from Apaches, but as none came near the town, the committee frequently saddled up and rode out in pursuit of raiders in the outlying communities. After the two April raids, some members of the committee announced that the raiders had come from the Aravaipa village near Camp Grant. Although Camp Grant was fifty-five miles distant, and it was unlikely that Aravaipas would have traveled that far to raid, the pronouncement was readily accepted by most of the Tucson citizens. In general they were opposed to agencies where Apaches worked for a living and were peaceful; such conditions led to reductions in military forces and a slackening of war prosperity.

During the last weeks of April, a veteran Indian fighter named William S. Oury began organizing an expedition to attack the unarmed Aravaipas near Camp Grant. Six Americans and forty-two Mexicans agreed to participate, but Oury decided this was

not enough to ensure success. From the Papago Indians, who years before had been subdued by Spanish soldiers and converted to Christianity by Spanish priests, he recruited ninety-two mercenaries. On April 28 this formidable band of 140 well-armed men was ready to ride.

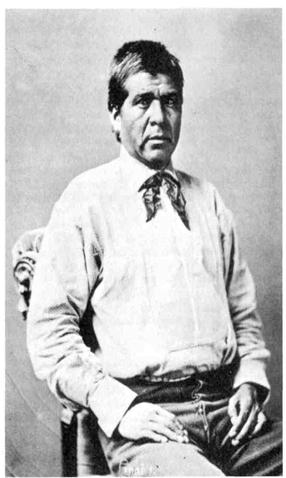

16. Eskiminzin, head chief of the Aravaipa Apaches. Photographed probably by Charles M. Bell in Washington, D.C., 1876. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

The first warning that Lieutenant Whitman at Camp Grant had of the expedition was a message from the small military garrison at Tucson informing him that a large party had left there on the twenty-eighth with the avowed purpose of killing all the Indians near Camp Grant. Whitman received the dispatch from a mounted messenger at 7:30

A.M.

on April 30.

“I immediately sent the two interpreters, mounted, to the Indian camp,” Whitman later reported, “with orders to tell the chiefs the exact state of things, and for them to bring their entire party inside the post. … My messengers returned in about an hour, with intelligence that they could find no living-Indians.”

6

Less than three hours before Whitman received the warning message, the Tucson expedition was deployed along the creek bluffs and the sandy approaches of the Aravaipas’ village. The men on the low ground opened fire on the wickiups, and as the Apaches ran into the open, rifle fire from the bluffs cut them down. In half an hour every Apache in the camp had fled, been captured, or was dead. The captives were all children, twenty-seven of them, taken by the Christianized Papagos to be sold into slavery in Mexico.

When Whitman reached the village it was still burning, and the ground was strewn with dead and mutilated women and children. “I found quite a number of women shot while asleep beside their bundles of hay which they had collected to bring in that morning. The wounded who were unable to get away had their brains beaten out with clubs or stones, while some were shot full of arrows after having been mortally wounded by gunshot. The bodies were all stripped.”

Surgeon C. B. Briesly, who accompanied Lieutenant Whitman, reported that two of the women “were lying in such a position, and from the appearance of their genital organs and of their wounds, there can be no doubt that they were first ravished

and then shot dead. … One infant of some ten months was shot twice and one leg hacked nearly off.”

7

Whitman was concerned that the survivors who had fled into the mountains would blame him for failing to protect them. “I thought the act of caring for their dead would be an evidence to them of our sympathy at least, and the conjecture proved correct, for while at the work many of them came to the spot and indulged in their expressions of grief too wild and terrible to be described … of the whole number buried [about a hundred] one was an old man and one was a well-grown boy—all the rest women and children.” Death from wounds and the discovery of missing bodies eventually brought the total killed to 144. Eskiminzin did not return, and some of the Apaches believed he would go on the warpath in revenge for the massacre.

“My women and children have been killed before my face,” one of the men told Whitman, “and I have been unable to defend them. Most Indians in my place would take a knife and cut his throat.” But after the lieutenant pledged his word that he would not rest until they had justice, the grieving Aravaipas agreed to help rebuild the village and start life over again.

Whitman’s persistent efforts finally brought the Tucson killers to trial. The defense claimed that the citizens of Tucson had followed the trail of murdering Apaches straight to the Aravaipa village. Oscar Hutton, the post guide at Camp Grant, testified for the prosecution: “I give it as my deliberate judgment that no raiding party was ever made up from the Indians at this post.” F. L. Austin, the post trader, Miles L. Wood, the beef contractor, and William Kness, who carried the mail between Camp Grant and Tucson, all made similar statements. The trial lasted for five days; the jury deliberated for nineteen minutes; the verdict was for release of the Tucson killers.

As for Lieutenant Whitman, his unpopular defense of Apaches destroyed his military career. He survived three court-martials on ridiculous charges, and after several more years of service without promotion he resigned.

The Camp Grant massacre, however, fixed the attention of Washington upon the Apaches. President Grant described the

attack as “purely murder,” and ordered the Army and the Indian Bureau to take urgent actions to bring peace to the Southwest.

In June, 1871, General George Crook arrived at Tucson to take command of the Department of Arizona. A few weeks later Vincent Colyer, a special representative of the Indian Bureau, arrived at Camp Grant. Both men were keenly interested in arranging a meeting with the leading Apache chiefs, especially Cochise.

Colyer first met with Eskiminzin in hopes of persuading him to return to his peaceful ways. Eskiminzin came down out of the mountains and said he would be glad to talk peace with Commissioner Colyer. “The commissioner probably thought he would see a great

capitán,”

Eskiminzin remarked quietly, “but he only sees a very poor man and not very much of a

capitán.

If the commissioner had seen me about three moons ago he would have seen me a

capitán.

Then I had many people, but many have been massacred. Now I have got few people. Ever since I left this place, I have been nearby. I knew I had friends here but I was afraid to come back. I never had much to say, but this I can say, I like this place. I have said all I ought to say, since I have few people anywhere to speak for. If it had not been for the massacre, there would have been a great many more people here now; but after that massacre who could have stood it? When I made peace with Lieutenant Whitman my heart was very big and happy. The people of Tucson and San Xavier must be crazy. They acted as though they had neither heads nor hearts … they must have a thirst for our blood. … These Tucson people write for the papers and tell their own story. The Apaches have no one to tell their story.”

Colyer promised to tell the Apaches’ story to the Great Father and to the white people who had never heard of it.

“I think it must have been God who gave you a good heart to come and see us, or you must have had a good father and mother to make you so kind.”

“It was God,” Colyer declared.

“It was,” Eskiminzin said, but the white men present could not tell in the translation whether he spoke in confirmation or was asking a question.

8

The next chief on Colyer’s agenda was Delshay of the Tonto Apaches. Delshay was a stocky, broad-shouldered man of about thirty-five. He wore a silver ornament in one ear, his facial expression was fierce, and he usually moved at a half-trot as though in a constant hurry. As early as 1868 Delshay had agreed to keep the Tontos at peace and use Camp McDowell on the west bank of the Rio Verde as his agency. Delshay, however, found the Bluecoat soldiers to be exceedingly treacherous. On one occasion an officer had fired buckshot into Delshay’s back for no reason the chief could fathom, and he was quite certain that the post surgeon had tried to poison him. After these occurrences, Delshay stayed clear of Camp McDowell.

Commissioner Colyer arrived at Camp McDowell late in September with authority to use soldiers to open communications with Delshay. Although truce flags, smoke signals, and night fires were used extensively by parties of cavalry and infantry, Delshay would not respond until he had thoroughly tested the intentions of the Bluecoats. By the time he agreed to meet with Captain W. N. Netterville in Sunflower Valley (October 31, 1871), Commissioner Colyer had returned to Washington to make his report. A copy of Delshay’s remarks was forwarded to Colyer.

“I don’t want to run over the mountains anymore,” Delshay said. “I want to make a big treaty. … I will make a peace that will last; I will keep my word until the stones melt.” He did not want to take the Tontos back to Camp McDowell, however. It was not a good place (after all, he had been shot and poisoned there). The Tontos preferred to live in Sunflower Valley near the mountains so they could gather the fruit and get the wild game there. “If the big

capitán

at Camp McDowell does not put a post where I say,” he insisted, “I can do nothing more, for God made the white man and God made the Apache, and the Apache has just as much right to the country as the white man. I want to make a treaty that will last, so that both can travel over the country and have no trouble; as soon as the treaty is made I want a piece of paper so that I can travel over the country as a white man. I will put a rock down to show that when it melts the treaty is to be broken. … If I make a treaty, I expect the big

capitán

will come and see me whenever I send for him, and I will

do the same whenever he sends for me. If a treaty is made and the big

capitán,

does not keep his promises with me I will put his word in a hole and cover it up with dirt. I promise that when a treaty is made the white man or soldiers can turn out all their horses and mules without anyone to look after them, and if any are stolen by the Apaches I will cut my throat. I want to make a big treaty, and if the Americans break the treaty I do not want any more trouble; the white man can take one road and I can take the other. … Tell the big

capitán

at Camp McDowell that I will go to see him in twelve days.”

9