Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (13 page)

Read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee Online

Authors: Dee Brown

After more parleying it was finally agreed that the Indians would remain camped on the Smoky Hill while seven chiefs went to Denver with Wynkoop to make peace with Governor Evans and Colonel Chivington. Black Kettle, White Antelope, Bull Bear, and One-Eye represented the Cheyennes; Neva, Bosse, Heaps-of-Buffalo, and Notanee the Arapahos. Little Raven and Left Hand, who were skeptical of any promises from Evans and Chivington, remained behind to keep their young Arapahos out of trouble. War Bonnet would look after the Cheyennes in camp.

Tall Chief Wynkoop’s caravan of mounted soldiers, the four white children, and the seven Indian leaders reached Denver on September 28. The Indians rode in a mule-drawn flatbed wagon fitted with board seats. For the journey, Black Kettle mounted his big garrison flag above the wagon, and when they entered the dusty streets of Denver the Stars and Stripes

fluttered protectively over the heads of the chiefs. All of Denver turned out for the procession.

Before the council began, Wynkoop visited Governor Evans for an interview. The governor was reluctant to have anything to do with the Indians. He said that the Cheyennes and Arapahos should be punished before giving them any peace. This was also the opinion of the department commander, General Samuel R. Curtis, who telegraphed Colonel Chivington from Fort Leavenworth that very day: “I want no peace till the Indians suffer more.”

11

Finally Wynkoop had to beg the governor to meet with the Indians. “But what shall I do with the Third Colorado Regiment if I make peace?” Evans asked. “They have been raised to kill Indians, and they must kill Indians.” He explained to Wynkoop that Washington officials had given him permission to raise the new regiment because he had sworn it was necessary for protection against hostile Indians, and if he now made peace the Washington politicians would accuse him of misrepresentation. There was political pressure on Evans from Coloradans who wanted to avoid the military draft of 1864 by serving in uniform against a few poorly armed Indians rather than against the Confederates farther east. Eventually Evans gave in to Major Wynkoop’s pleadings; after all, the Indians had come four hundred miles to see him in response to his proclamation.

12

The council was held at Camp Weld near Denver, and consisted of the chiefs, Evans, Chivington, Wynkoop, several other Army officers, and Simeon Whitely, who was there by the governor’s order to record every word said by the participants. Governor Evans opened the proceedings brusquely, asking the chiefs what they had to say. Black Kettle replied in Cheyenne, with the tribe’s old trader friend, John S. Smith, translating:

“On sight of your circular of June 27, 1864, I took hold of the matter, and have now come to talk to you about it. … Major Wynkoop proposed that we come to see you. We have come with our eyes shut, following his handful of men, like coming through the fire. All we ask is that we may have peace with the whites. We want to hold you by the hand. You are our father. We have been traveling through a cloud. The sky has

been dark ever since the war began. These braves who are with me are willing to do what I say. We want to take good tidings home to our people, that they may sleep in peace. I want you to give all these chiefs of the soldiers here to understand that we are for peace, and that we have made peace, that we may not be mistaken by them for enemies. I have not come here with a little wolf bark, but have come to talk plain with you. We must live near the buffalo or starve. When we came here we came free, without any apprehension, to see you, and when I go home and tell my people that I have taken your hand, and the hands of all the chiefs here in Denver, they will feel well, and so will all the different tribes of Indians on the plains, after we have eaten and drunk with them.”

Evans replied: “I am sorry you did not respond to my appeal at once. You have gone into an alliance with the Sioux, who are at war with us.”

Black Kettle was surprised. “I don’t know who could have told you this,” he said.

“No matter who said this,” Evans countered, “but your conduct has proved to my satisfaction that was the case.”

Several of the chiefs spoke at once then: “This is a mistake; we have made no alliance with the Sioux or anyone else.”

Evans changed the subject, stating that he was in no mood to make a treaty of peace. “I have learned that you understand that as the whites are at war among themselves,” he went on, “you think you can now drive the whites from this country, but this reliance is false. The Great Father at Washington has men enough to drive all the Indians off the plains, and whip the Rebels at the same time. … My advice to you is to turn on the side of the government, and show by your acts that friendly disposition you profess to me. It is utterly out of the question for you to be at peace with us while living with our enemies, and being on friendly terms with them.”

White Antelope, the oldest of the chiefs, now spoke: “I understand every word you have said, and will hold on to it. … The Cheyennes, all of them, have their eyes open this way, and they will hear what you say. White Antelope is proud to have seen the chief of all the whites in this country. He will tell his people. Ever since I went to Washington and received this medal, I

have called all white men as my brothers. But other Indians have been to Washington and got medals, and now the soldiers do not shake hands, but seek to kill me. … I fear that these new soldiers who have gone out may kill some of my people while I am here.”

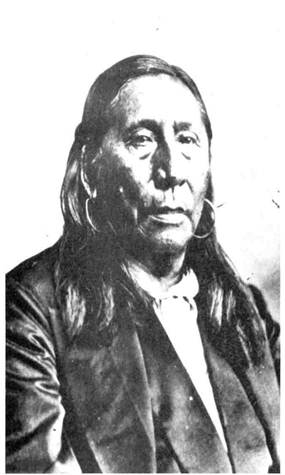

6. Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs meeting at the Camp Weld Council on September 28, 1864. Standing, third from left: John Smith, interpreter; to his left, White Wing and Bosse. Seated left to right: Neva, Bull Bear, Black Kettle, One-Eye, and an unidentified Indian. Kneeling left to right: Major Edward Wynkoop, Captain Silas Soule.

Evans told him flatly: “There is great danger of it.”

“When we sent our letter to Major Wynkoop,” White Antelope continued, “it was like going through a strong fire or blast for Major Wynkoop’s men to come to our camp; it was the same for us to come to see you.”

Governor Evans now began to question the chiefs about specific incidents along the Platte, trying to trap some of them into admitting participation in raids. “Who took the stock from Fremont’s Orchard,” he asked, “and had the first fight with the soldiers this spring north of there?”

“Before answering that question,” White Antelope replied boldly, “I would like for you to know that this was the beginning of the war, and I should like to know what it was for. A soldier fired first.”

“The Indians had stolen about forty horses,” Evans charged. “The soldiers went to recover them, and the Indians fired a volley into their ranks.”

White Antelope denied this. “They were coming down the Bijou,” he said, “and found one horse and one mule. They returned one horse before they got to Gerry’s to a man, then went to Gerry’s expecting to turn the other one over to someone. They then heard that the soldiers and Indians were fighting down the Platte; then they took fright and all fled.”

“Who committed depredations at Cottonwood?” Evans demanded.

“The Sioux; what band, we do not know.”

“What are the Sioux going to do next?”

Bull Bear answered the question: “Their plan is to clean out all this country,” he declared. “They are angry, and will do all the damage to the whites they can. I am with you and the troops, to fight all those who have no ears to listen to what you say. … I have never hurt a white man. I am pushing for something good. I am always going to be friends with whites; they can do me good. … My brother Lean Bear died in trying to keep peace

with the whites. I am willing to die the same way, and expect to do so.”

As there seemed little more to discuss, the governor asked Colonel Chivington if he had anything to say to the chiefs. Chivington arose. He was a towering man with a barrel chest and a thick neck, a former Methodist preacher who had devoted much of his time to organizing Sunday schools in the mining camps. To the Indians he appeared like a great bearded bull buffalo with a glint of furious madness in his eyes. “I am not a big war chief,” Chivington said, “but all the soldiers in this country are at my command. My rule of fighting white men or Indians is to fight them until they lay down their arms and submit to military authority. They [the Indians] are nearer to Major Wynkoop than anyone else, and they can go to him when they are ready to do that.”

13

And so the council ended, leaving the chiefs confused as to whether they had made peace or not. They were sure of one thing—the only real friend they could count on among the soldiers was Tall Chief Wynkoop. The shiny-eyed Eagle Chief, Chivington, had said they should go to Wynkoop at Fort Lyon, and that is what they decided to do.

“So now we broke up our camp on the Smoky Hill and moved down to Sand Creek, about forty miles northeast of Fort Lyon,” George Bent said. “From this new camp the Indians went in and visited Major Wynkoop, and the people at the fort seemed so friendly that after a short time the Arapahos left us and moved right down to the fort, where they went into camp and received regular rations.”

14

Wynkoop issued the rations after Little Raven and Left Hand told him the Arapahos could find no buffalo or other wild game on the reservation, and they were fearful of sending hunting parties back to the Kansas herds. They may have heard about Chivington’s recent order to his soldiers: “Kill all the Indians you come across.”

15

Wynkoop’s friendly dealings with the Indians soon brought him into disfavor with military officials in Colorado and Kansas. He was reprimanded for taking the chiefs to Denver without authorization, and was accused of “letting the Indians run things at Fort Lyon.” On November 5, Major Scott J. Anthony, an

officer of Chivington’s Colorado Volunteers, arrived at Fort Lyon with orders to relieve Wynkoop as commander of the post.

One of Anthony’s first orders was to cut the Arapahos’ rations and to demand the surrender of their weapons. They gave him three rifles, one pistol, and sixty bows with arrows. A few days later when a group of unarmed Arapahos approached the fort to trade buffalo hides for rations, Anthony ordered his guards to fire on them. Anthony laughed when the Indians turned and ran. He remarked to one of the soldiers “that they had annoyed him enough, and that was the only way to get rid of them.”

16

The Cheyennes who were camped on Sand Creek heard from the Arapahos that an unfriendly little red-eyed soldier chief had taken the place of their friend Wynkoop. In the Deer Rutting Moon of mid-November, Black Kettle and a party of Cheyennes journeyed to the fort to see this new soldier chief. His eyes were indeed red (the result of scurvy), but he pretended to be friendly. Several officers who were present at the meeting between Black Kettle and Anthony testified afterward that Anthony assured the Cheyennes that if they returned to their camp at Sand Creek they would be under the protection of Fort Lyon. He also told them that their young men could go east toward the Smoky Hill to hunt buffalo until he secured permission from the Army to issue them winter rations.

Pleased with Anthony’s remarks, Black Kettle said that he and the other Cheyenne leaders had been thinking of moving far south of the Arkansas so that they would feel safe from the soldiers, but that the words of Major Anthony made them feel safe at Sand Creek. They would stay there for the winter.

After the Cheyenne delegation departed, Anthony ordered Left Hand and Little Raven to disband the Arapaho camp near Fort Lyon. “Go and hunt buffalo to feed yourselves,” he told them. Alarmed by Anthony’s brusqueness, the Arapahos packed up and began moving away. When they were well out of view of the fort, the two bands of Arapahos separated. Left Hand went with his people to Sand Creek to join the Cheyennes. Little Raven led his band across the Arkansas River and headed south; he did not trust the Red-Eyed Soldier Chief.

Anthony now informed his superiors that “there is a band of Indians within forty miles of the post. … I shall try to keep

the Indians quiet until such time as I receive reinforcements.”

17