Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream (8 page)

Read Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream Online

Authors: Deepak Chopra,Sanjiv Chopra

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General

The answers ranged from chauffeured car to a walk of many miles: “We heard of Dr. Chopra in our village. We came by bus so he can make the diagnosis.”

Sometimes, rather than charging them anything she would give them twenty rupees for their return fare.

The story that best exemplifies the values that I was taught by my mother actually took place after Deepak and I had left home to become doctors ourselves. But her actions in this situation were no different than they had been at any time while we were growing up. Our parents were living in a house they had built in an area of Delhi called Defence Colony. About nine o’clock in the evening, their cook, Shanti, was placing food on the table when the doorbell rang. That wasn’t at all unusual in and of itself—patients often came by the house at night.

Shanti went to answer the door, and a minute later my parents heard unusual sounds. Suddenly three young men pushed Shanti

into the dining room, covered in blood from a cut on his head. All three of the intruders had knives, and one of them also had a gun. They started screaming at my parents, making all kinds of threats. My mother stood up to them.

“I know what you want,” she said. “Money and jewelry. We’ll give you whatever we have in the house. Your need seems to be greater than ours. Here you are.” She took off the jewelry she was wearing and handed it to them.

“That’s not enough,” the leader yelled. He demanded the keys to the safe and forced them into the bedroom.

My mother handed him the keys and began helping him open it, when she realized one of the robbers was still beating Shanti. That was when she finally got angry.

“Stop that!” she screamed at him. “He has two young children. If you want to kill someone, kill my husband and me. We’ve had a good life and our children are well settled. But don’t you dare beat this young man. He’s done nothing to you and we’re giving you what you want.”

The thieves looked at one another, unsure what to do. They stopped beating Shanti. Suddenly the leader tossed the earrings my mother had given him onto the bed, then bent down and touched my mother’s feet, a gesture of great respect for older people and a way of asking for their blessing.

“I forgive you,” my mother said, “and I hope you mend your ways.”

“You have been very kind,” he said. “It doesn’t seem right for us to take everything. Your face looks bare without your earrings.” He turned to the other thieves. “And I recognize this man. He’s the doctor who treated my father seven years ago. Let’s go.”

They tied up my parents and Shanti and locked them in a bathroom. Before leaving, however, the leader of the gang warned them not to identify them to the police, threatening to come back to harm them if they did. My mother gave him her word she would not.

My mother, who was then in her fifties, untied my father’s ropes with her teeth and then called the police. The robbers were clumsy and left several clues, including their fingerprints, and were quickly

arrested. But when my mother was told that to recover her jewelry she would have to pick the robbers out of a lineup, she refused, explaining that she had made a pledge and her word was more important to her than jewelry.

A few months later the leader escaped from prison and was killed in a fight with the police.

My mother also tended to our manners, teaching us proper behavior. These lessons I remember very well. She drilled into Deepak and me that when we were offered anything we were never to simply take it; we had to be offered something three times before accepting. Three times—she was very clear about that.

My favorite dessert was a sweet called

Rasgulla.

When I was five years old, my family was having dinner at my uncle’s house, and my aunt offered me rasgulla. I remembered my lesson.

“No, thank you,” I said. That was one.

“Come on,” she said. “Don’t you like sweets?”

“No, thank you,” I repeated. “I’m okay.” That’s two.

But then, instead of offering it to me for a third time, she moved on to the next person. Wait a second.

“Auntie,” I called out. “Can you please come back and offer it one more time?”

Growing up, Deepak and I had very different interests. Deepak was always more scholarly than I was; I was the better athlete. While he was reading newspapers and books and grappling with philosophical questions, I was playing cricket, soccer, field hockey, or table tennis, or I was running marathons, pole vaulting, and high jumping; if there was a competition I wanted to be part of it, even if it was just throwing darts. In fact, my best friend and I would often race each other—Deepak’s job was to blow the whistle to start the race and to time us.

So while Deepak was winning academic honors, I was filling a trunk with athletic trophies. Deepak worried constantly that I wasn’t studying enough or finishing my work. He would even complain to

our mother: “Sanjiv hasn’t done his homework and he won’t come in the house.” Let him play, she would say, let him play.

Like my brother, I have a strong visual memory, and in India we were taught by rote. A lot of schoolwork simply required learning to repeat what was on the page, and that was never difficult for me. I was always able to get my work done and get good grades. I had discipline; I was focused and organized. From a young age, I set goals and worked until I had accomplished them.

That said, my mind occasionally wandered at school. If our teachers caught us doing that, they would rap us on the knuckles with a ruler. They said they were disciplining us for our own good. Admittedly I was more than once the subject of their benevolence.

Of course, without television, computers, or video games we had few distractions. In fact, when I was ten years old I won an award in school, and the prize was a book about American television. I had never seen television but I loved that book. I just stared at the black-and-white photographs of this box with people in it for hours. It was amazing to me. I learned about television stars like Jack Benny and Milton Berle. While Deepak was reading about politics and philosophy, I became fascinated by this amazing device.

Growing up, Deepak did things the way they were supposed to be done. Perhaps this was because he was my older brother and thus felt a greater degree of responsibility. Me? I was always poking at things and breaking the rules. I was certainly more of a free spirit than my brother ever was.

But it was safe for me to be that way—I knew that Deepak was there looking out for me.

5

..............

Miracles in Hiding

Deepak

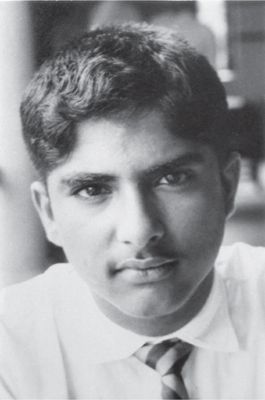

Deepak self-portrait, 1961. He was fourteen years old when he won an essay competition for “The Nature of Time” at St. Columba’s.

M

IRACLES ARE SLIPPERY.

We all want them to exist, but if they did, it would turn the ordinary world upside down. Imagine airplanes needing a miracle to stay aloft in the sky. Every passenger would be praying, not just the ones with an extreme fear of flying. A safe landing would display the grace of God; a disastrous crash the wrath of God. It’s much safer to know that airplanes fly because of a principle in physics, Bernoulli’s principle, which allows flowing air to lift a wing. Millions of people trust airplanes to work without understanding Bernoulli’s principle, because they know that science is more reliable than faith. Miracles are flashy, but you wouldn’t bet your life on one at the airport.

When I was growing up in India, this whole scheme of the rational and predictable hadn’t yet taken hold. As wobbly as miracles are considered in the West, they were cherished in the East. A miracle didn’t defy the laws of physics or make everything uncertain. It proved the existence of God (which no one doubted anyway). More than that, a miracle justified the entire world of my ancestors. In their reality God had a finger in every pie. That fact was deeply reassuring. God saw you. He cared for your existence, and the fact that miracles were so slippery—they always happened to someone you didn’t know or someone who had been conveniently dead for several hundred years—only added to the glory of a divine mystery.

My father, as a Western-trained physician, was one of those who shredded the mystery. He was surrounded by people who clung to a miraculous reality. One of his brothers, a traveling salesman for field hockey equipment, was fond of visiting every holy man he could find. He firmly believed that simply sitting in the presence of a saint, as all holy men were commonly called, brought him closer to God. In my father’s eyes this behavior was a holdover from the old, superstitious India that needed to disappear. By implication he wasn’t just embarrassed

when poor villagers revered him. They were displaying ignorance about modern medicine, something he spent his life trying to wipe out.

But there were still things to marvel at, even revere, in my father’s rational scheme. One evening, when I was seven, he came home from work in a state of barely suppressed excitement. I think this was the first time I ever saw him break out of his normal reserve.

“Quickly, son. Wash your face, straighten your clothes. We leave in two minutes.”

By the time I was ready, my father was straddling his bicycle outside.

“Come. Hurry!”

He tapped the handlebars, and I hopped on. We rushed into the twilight together, leaving my mother and four-year-old Sanjiv at home—he was too young for this adventure, whatever it was, and she had to take care of him. Daddy pedaled furiously through the balmy streets of Pune, refusing to tell me where we were going.

“You’ll see. Just hold on.”

Together his secrecy and excitement made my imagination run away with me, or would have if I didn’t have to focus on not pitching off the handlebars as he veered around corners. We weaved through the same assortment of vehicles and animals you still find outside the main cities: cars, motorbikes, scooter rickshaws, other cyclists, and bullock carts. Only in my childhood, there were fewer cars and more carts. We raced through the city’s bazaars, and in my mind I remember—adding to the romance of our adventure—that I begged Daddy to stop and let me watch a snake charmer by the side of the road. He was about to pit a cobra against a mongoose in a deadly fight.

But memory plays tricks after so many years. I was a seven-year-old boy on an adrenaline high who had seen more than his share of those fatal combats. It is unlikely that a snake charmer would have been performing after dark on those dimly lit streets.

The crowd that awaited us wasn’t imaginary, though. It was just disappointing: a large group of properly dressed men sitting in an assembly hall. No wives or children. My father found two of the last

remaining chairs and greeted a few of the other men. We were in the British army barracks where he worked. The hall was part of the small brick building known as the MI Room (short for military incidents), where the doctors treated every form of illness and injury.

My one remaining hope was that I had been hauled off into the night to witness a medical monstrosity. Instead, an English gentleman in a frock coat and spectacles mounted the stage to loud applause. He bowed slightly, then began to lecture with fuzzy slides projected on a makeshift screen, his voice proper and dull. The slides showed lots of white dots with halos around them.

My father was enraptured. I was an overstimulated seven-year-old. I quickly fell asleep leaning against my father’s warm side.

Daddy was still exuberant when he woke me up and perched me back on the handlebars. We pedaled home slowly, his hand on my shoulder to steady me.

“Do you know who that was?” he asked. “He’s Fleming, the man who discovered penicillin.”

“Where is Penicillin?” It sounded farther away than Pondicherry or even London.

To which my father laughed. He told me the story of the little white dots and the lives saved because of the curative powers of common bread mold. For centuries, he explained, moldy loaves of bread had been thrown away without anyone suspecting that a miracle lay hidden inside the fuzzy green growth that made the bread unfit to eat. It was a boon to humanity that Sir Alexander Fleming had paused to look more closely instead of throwing out some petri dishes of bacteria that had been “ruined” by the same mold.

Everyone agrees that miracles lie hidden. A yogi meditates in a remote Himalayan cave; penicillin sat under our very noses. The question is: What brings the miracles to light? There seem to be only two choices. Either the grace of God reveals miracles, or the rational mind uncovers them by going deeper into the construct of the physical world. Strangely as I grew older, I seemed to belong to the small camp that rejected either/or. Couldn’t a miracle be right under our noses, woven into the fabric of nature, and still be evidence of God?

Imagine a world where Sir Alexander Fleming shows slides of a levitating yogi with a halo around him. That would come very close to my ideal.

I never heard any complaints from my father about the superstition that was rife in his own family. He avoided the irrational with polite silence and was blind to anything that could not be explained by science. All around him, however, human nature took its course, falling in love with anything that was as irrational and inexplicable as possible. A special focus of our credulity—I was part of the irrational pack for a long time—was my uncle Tilak, who was five years younger than my father.