Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream (7 page)

Read Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream Online

Authors: Deepak Chopra,Sanjiv Chopra

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General

I’ve already mentioned that a character trait was building invisibly inside me around authority. I saw myself trying to please authority but with a streak of resentment. I cannot say if being caned made the trait stronger or not. A rebel wasn’t created overnight. The mixture of influences in the psyche is too subtle to tease apart.

But years later, when I was serving a residency in Boston, I preferred angry rebellion to the prospect of another dose of humiliation. As a young doctor in his twenties, a fellowship placed me with one of the leading endocrinologists in the country. My passion for study hadn’t abated. I had already finished one two-year residency and passed the boards in internal medicine. At that time, in the early Seventies, a resident needed a good fellowship just to make ends meet, and I had a young family to support. But I wasn’t happy in my work. My supervisor was overbearing, and all my time was spent in his laboratory, either injecting rats with iodine or dissecting them to see how the iodine had affected them.

Endocrinology, which is the study of the hormones secreted by the endocrine system, is a precise, technical specialty. I was more enthusiastic about seeing patients than toiling in the lab, but I was still fascinated by the detective work. Forty years later, the investigation of the three hormones secreted by the thyroid gland seems very basic, but at the time the fact that my supervisor was one of the pioneers in studying the Reverse T

3

hormone was big news. We worked in an atmosphere of tense one-upmanship, competing with other research teams in the field—the thyroid was supposed to be our whole world.

I was an immigrant who had embraced Boston medicine for its prestige and potential, but associations with India swirled around me. A colleague from medical school back home, coincidentally named Inder Chopra, had played a major role in identifying Reverse

T

3

. And the rat is sacred to the god Ganesha. Not that a shred of the sacred remains when you have a dissecting scalpel in hand. I didn’t miss its absence, back then.

My discontent came to a head during a routine staff meeting. My supervisor quizzed me on a technical detail in front of the group: “How many milligrams of iodine did Milne and Greer inject into the rats in their 1959 paper?” This referred to some seminal experimental work, but I answered offhandedly, because he didn’t really want the information, only to put me on the spot.

“Maybe two-point-one milligrams. I’ll look it up.”

“This is something you should have in your head,” he barked, irritated. Everyone in the room grew quiet.

I got up, walked over to him, and dumped a bulky file of papers on him.

“Now you have it in your head,” I said, and walked out.

My supervisor followed me into the parking lot. I was agitated, fumbling to start my beat-up Volkswagen Beetle, the signature vehicle of struggling young professionals. He leaned in, speaking with studied control to disguise his anger.

“Don’t,” he warned. “You’re throwing away your whole career. I can make that happen.”

Which was quite true. The word would go out, and with his disapproval I had no future in endocrinology. But in my mind I wasn’t walking away from a career. I was standing up to someone who had tried to humiliate me in front of the group. My impulsive rebellion was instinctive and yet very unlike me. At such a precipitous turning point, no one, I think, reaches inside to find a store of memories that build to that moment. We construct reasons for our behavior after the fact, adding to the story of our lives arbitrarily. But as erratic as our reasons may be as we tick them off in our heads, they are always self-serving. The ego plunges impulsively into a situation, after which the shadowy part of the psyche begins to rise to the surface, bringing with it those insecure things we call second thoughts: guilt, regret, reliving the past, self-recrimination, panic, alarm about the future. The ego has to regroup around these subtle but persistent attackers.

A process starts that no one has control over, negotiating between all the psychic forces that make demands upon us. Some people are self-reflective; they engage consciously in the whole process and meet it head on. Most people do the reverse. They try to distract themselves and manage to escape the underground war going on inside them—except for the inescapable late-night hours when sleep won’t come and the shadows of the mind roam without check.

I belonged in the second camp. I managed to start the VW and left him standing there in the hospital parking lot, fuming and vindictive. Word did go out, and I faced the prospect of having no job except for any moonlighting work that might come my way, the lowest paying drudgery in Boston medicine. Pain would follow. I knew this less than five minutes down the road. It made me stop off at a bar before going home to break the devastating news to Rita.

What mystified me was the complete turnaround I had just made. Everything in my upbringing had instilled a respect for authority: the charmed circle, the duty of Rama to protect his younger brother, the caning after the cricket match. The hardest traits to change are the ones that have seeped into us so thoroughly they become a part of us. The fact that you have absorbed a trait doesn’t make it normal, but even the most insidious aspects of the mind do feel normal; that’s what makes them insidious.

In religion there’s an old saw: No one is more dangerous to the faith than an apostate. Boston medicine was the true faith. I had no intention of renouncing it. If you had questioned me the day before I dumped a file on an eminent doctor’s head, I would have sworn allegiance. Frankly I had no reason to change sides, not rationally. You don’t walk away from a church when there is no other church to go to. But the only way to see if there are demons lurking outside the circle is to crawl over the boundary that protects you. This was the real start of a revelatory life. I can’t take credit for any of the revelations, but a hidden force inside me was invisibly preparing the way.

4

..............

Lucky Sari

Sanjiv

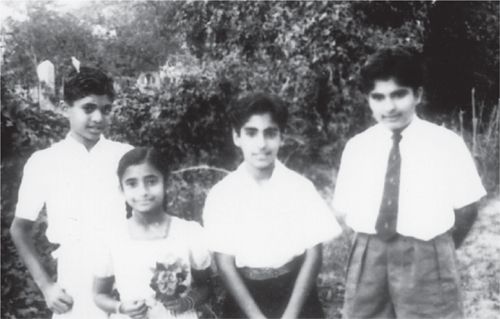

Chopra brothers with their childhood friends, Ammu Sequeira and Prasan Rao, on their way to school, Jabalpur, 1956.

M

Y PATERNAL GRANDMOTHER

was an uneducated, rather docile woman, but she was also very wise, and feisty when necessary. While she never graduated from high school, she taught us that education doesn’t come just from books. My father often told Deepak and me a memorable story: One afternoon, when he was five years old, he was in the kitchen having lunch with his younger brother and his younger brother’s best friend, Ilyas, a Muslim.

In their house, the kitchen sat right next to the prayer room. Unexpectedly a local priest, a pundit as they were called, dropped by to visit, as he often did. When this pundit saw Ilyas in the kitchen, he was outraged.

“You pretend to be very religious,” he told my grandmother, “yet you have a Muslim boy sitting in your kitchen, right next to the Hindu gods and goddesses. God will never forgive you.”

Deepak and I never heard my grandmother raise her voice, but apparently she did that time. At least that’s the way our father told the story.

“How dare you talk to me like that,” she said. “Ilyas is my son’s friend, so he is like my son. What is all this Hindu-Muslim business? My God doesn’t know about that. Get out of my house right now and take your God with you. And never, ever enter this house again.” And she threw him out.

While my father taught us the value of education and made sure we attended the best possible British schools, it was the women in our family who taught us to acknowledge and appreciate our spiritual side and who showed us the meaning of respect and compassion. My paternal grandmother was half-Sikh and taught us the values of that religion. To explain Sikhism she would tell us stories of its founder, Guru Nanak.

One day Guru Nanak was taking a nap on a cart. A Muslim priest noticed his feet were pointing directly toward a mosque. He angrily shook him awake.

“How dare you,” the priest scolded him. “You’ve fallen asleep with your feet pointing to Allah. Blasphemy!”

“Please forgive me, learned man,” Guru Nanak responded gently. “I apologize for my sin. Please, point my feet to where Allah is not.”

With stories like this one, our father’s mother taught us the dangers of believing that one god, any particular god, is somehow superior to other gods, which is the basis of respect for all beliefs. It was her way of reminding Deepak and me to keep our minds open to the values of other people.

That was reinforced by my mother, of course, who lived her life believing that no one human being was better than another. She steadfastly refused to subscribe to the caste system. My mother simply had faith. There really isn’t any other way of describing her, although this story comes pretty close. In 1957 my parents were living in Jabalpur, and independent India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, was coming to town to reopen a weapons factory that would now be building Mercedes-Benz trucks for the army.

Most Americans are aware of the contributions of Gandhi, who led a great revolution by practicing passive resistance, but in India Nehru was equally beloved. Together they had led India out of British servitude. Nehru was an extraordinarily charismatic man and a brilliant leader who carefully plotted the path that has led to modern India. India today is a result of his vision. For many in India, he was as much George Washington as he was Martin Luther King Jr.

Weeks before his arrival in Jabalpur, people began making preparations for a momentous greeting. My mother worried constantly about which sari she would wear for this occasion. My father couldn’t understand the fuss.

“What difference does it make?” he asked. “There will be millions of people in the streets. He’s not going to notice your sari.” But she insisted on buying a new sari anyway.

“He’s going to notice me,” she said. “He’s going to acknowledge

me.” Of course that wasn’t going to happen. Nehru didn’t know my mother. But she had faith it would happen.

Nehru’s parade route took him past our house on Narbada Road. At four thirty in the morning, we were all dressed up and standing in the street. My father was wearing his army uniform, all his medals shined. Deepak and I wore our school jackets and ties. And my mother was wearing her new sari. By 7:00 a.m., hundreds of thousands of people lined the road, and the police had erected barriers to hold them back. We waited a long time, but suddenly a small convoy came around the corner. The prime minister was standing in the back of a jeep, waving casually to everyone. The crowd was screaming, “Long live Nehru! Long live Nehru!”

As Nehru’s jeep came slowly down the street the roar grew deafening. The people all around us were screaming, shouting, reaching out to touch him; he continued waving. But as his jeep passed in front of us, Nehru suddenly took the rose he always wore from his lapel and tossed it almost directly in front of my mother. She picked it up and looked at my father.

“What did I tell you?”

We went back into the house and placed that rose in a vase and then took everything else out of that room. For three weeks people came to our house from all over the city just to see the rose that Mr. Nehru had given to Mrs. Chopra. At the end of that time, she threw a party and gave everyone in attendance a rose petal. For some people it became a family heirloom to be handed down from generation to generation.

But the part that stays with me is that my mother never doubted for an instant that the prime minister was going to acknowledge her. As irrational as it seemed, she had faith.

There was at least one situation in which her faith went a little too far. My mother was a cricket fan. In 1959 the powerful Australian team came to India to play a weak Indian team. International cricket matches were extremely important in India. The whole country would come to a grinding halt—people would skip work, children would stay home from school, the traffic would disappear from the

streets. Nobody gave India much of a chance to win this match. But in what is still known as the Miracle at Kanpur, an aging cricketer named Jasu Patel became a national legend by taking an extraordinary nine wickets out of ten. That would be like hitting four home runs—in one inning. My mother was sitting by the radio listening to the match on All India Radio. She happened to be wearing a favorite sari that day, as did many sports fans, because she was convinced that what she was wearing was good luck. So for the next forty years, every time India played an international cricket match she wore that sari. The fact that India lost the majority of those matches didn’t bother her. When Deepak and I teased her about it, she was unperturbed.

“Say what you want. I’m still going to wear that sari.” And so she did. Even the dry cleaner would know when an international cricket match was in the offing.

Our mother demonstrated her compassion every day with the patients who came to my father’s medical office in our home. She would greet them at the door herself.

“How did you come?” she would ask.