Brilliant Blunders: From Darwin to Einstein - Colossal Mistakes by Great Scientists That Changed Our Understanding of Life and the Universe (29 page)

Authors: Mario Livio

Based solely on what I have described so far, I think most people would agree that it seems only fair to attribute the discovery of the expanding universe and of the tentative existence of Hubble’s law to Lemaître, and the detailed confirmation of that law to Hubble and Humason. The subsequent, truly meticulous observations of Hubble and Humason extended Slipher’s velocity measurements to greater and much more accurate distances. Here, however, is where the plot thickens.

The English translation of Lemaître’s 1927 paper was published in the

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

in England in March 1931. However, a few paragraphs from the original French version were deleted—in particular, the paragraph that described Hubble’s law and in which Lemaître used the forty-two galaxies for which he had (approximate) distances and velocities to derive a value for the Hubble constant of 625. Also missing were one paragraph in which Lemaître discussed the possible errors in the distance estimates, and two footnotes, in one of which he remarked on the interpretation of the proportionality between the velocity and distance as resulting from a relativistic expansion. In the same footnote, Lemaître also calculated two possible values for the Hubble constant: 575 and 670, depending on how the data were grouped.

Who translated the article? And why were these paragraphs deleted from the English version? Several history-of-science amateur sleuths suggested in 2011 that someone had deliberately censored those parts of Lemaître’s paper that dealt with Hubble’s law and the determination of the Hubble constant.

Canadian astronomer Sidney van den Bergh speculated that whoever did the “selective editing” did so to prevent Lemaître’s paper from undermining

Edwin Hubble’s priority claim. “Picking out part of the middle of an equation must have been done on purpose,” he noted. South African mathematician

David Block went even somewhat further. He suggested that Edwin Hubble himself might have had a hand in this cosmic “censorship” to ensure that credit for the discovery of the expanding universe would go to himself and the Mount Wilson Observatory, where he made the observations.

As someone who has worked for more than two decades with Hubble’s namesake—the Hubble Space Telescope—I became sufficiently intrigued by this whodunit to attempt to appraise the facts more carefully. I started by examining the circumstances surrounding the translation of Lemaître’s article.

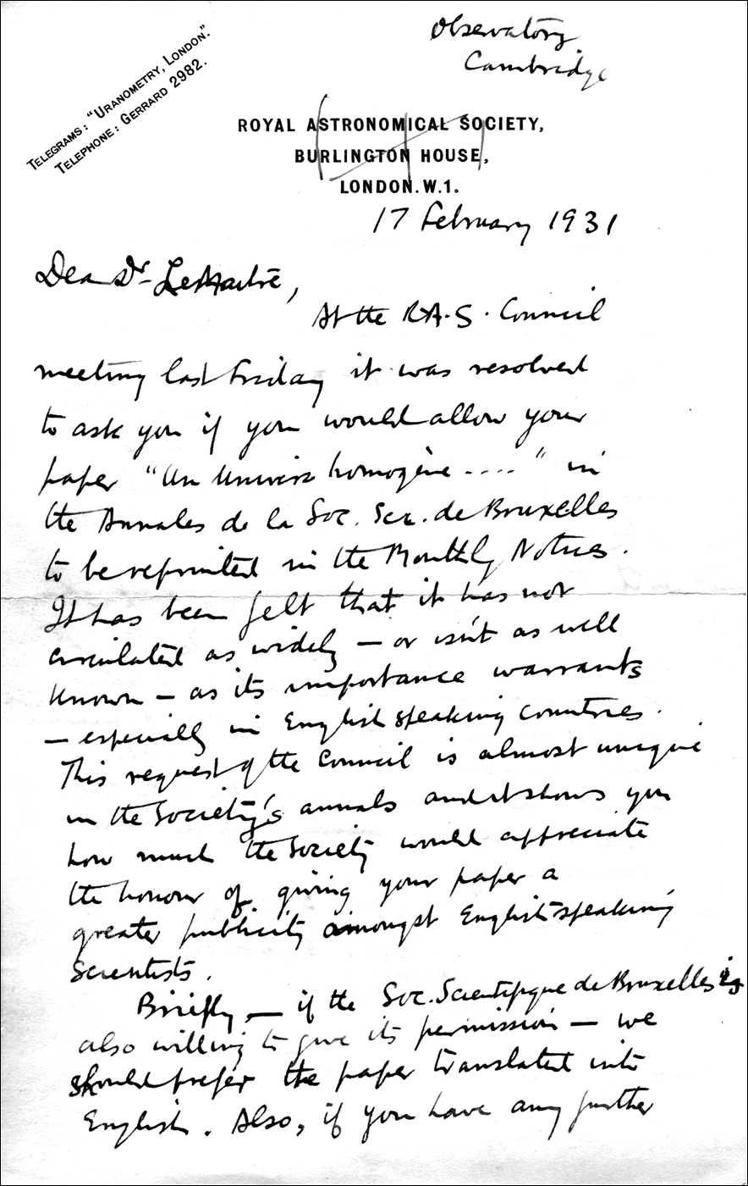

First, I obtained a copy of the original letter sent by the editor of the

Monthly Notices

at the time, astronomer William Marshall Smart, to Georges Lemaître. In that letter (figure 26), Smart asked Lemaître whether he would allow his 1927 paper to be reprinted in the

Monthly Notices,

since the Royal Astronomical Council felt that the paper was not as well known as its importance deserved. The most important paragraph in the letter reads:

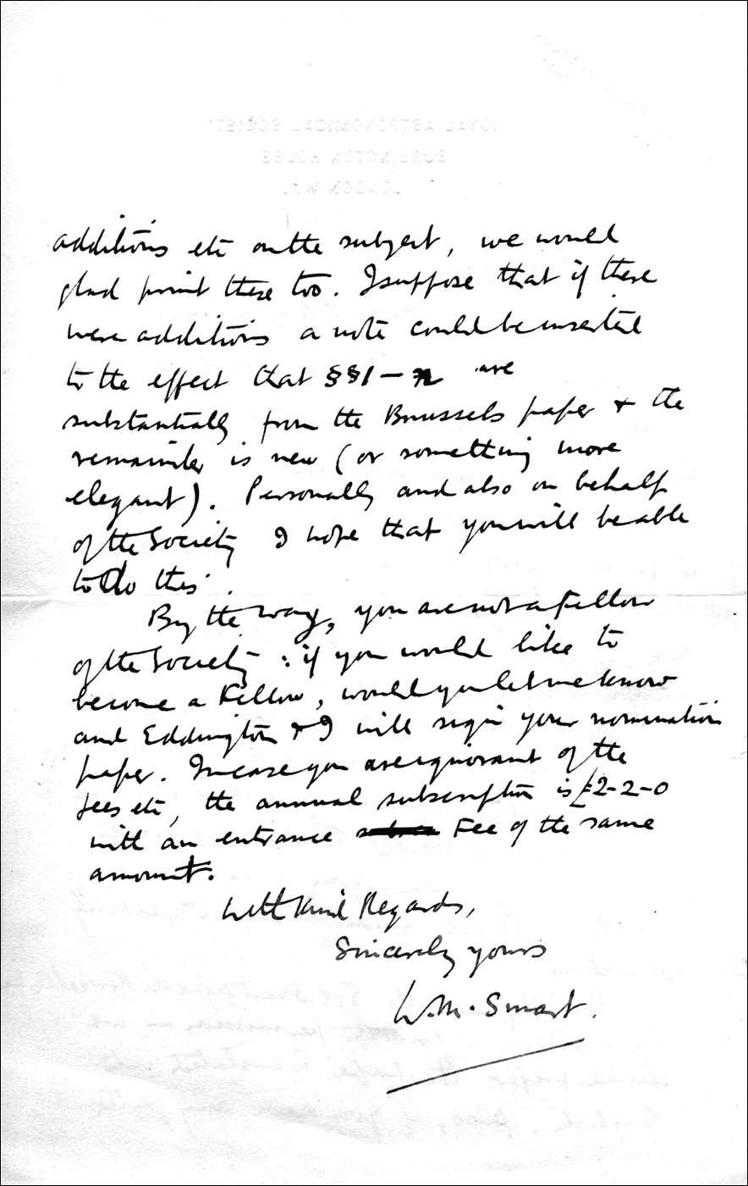

Briefly—if the Soc. Scientifique de Bruxelles [in the annals of which the original paper was published] is also willing to give its permission—we should prefer the paper translated into English. Also, if you have any further additions etc. on the subject, we would glad[ly] print these too. I suppose that if there were additions a note could be inserted to the effect that §§–n are substantially from the Brussels paper + the remainder is new (or something more elegant). Personally and also on behalf of the Society I hope that you will be able to do this.

My immediate reaction was that the text of Smart’s letter was entirely innocent, and it certainly did not suggest

any intent of extra editing or censorship. But while I was fairly convinced of the correctness of this nonconspiratorial interpretation of Smart’s letter, the two main

mysteries—who translated the paper and who deleted the paragraphs—remained unresolved. In an attempt to answer these questions definitively, I decided to explore the matter further by scrutinizing all of the council’s minutes and the entire surviving correspondence from 1931 at the Royal Astronomical Society Library in London. After going through many hundreds of irrelevant documents and almost giving up, I discovered two “smoking guns.” First,

in the minutes of the council from February 13, 1931, it is reported: “On the motion of Dr. Jackson it was resolved that the Abbé Lemaître be asked if he would allow his paper ‘Un Univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant,’ or an English translation thereof, to be published in the Monthly Notices.” This, of course, was precisely the decision mentioned in Smart’s letter to Lemaître. (As an amusing aside, the same minutes also report, “A motion by Sir Arthur Eddington that smoking be permitted at meetings of the Council was discussed. It was resolved that smoking be permitted after 3:30 p.m.”)

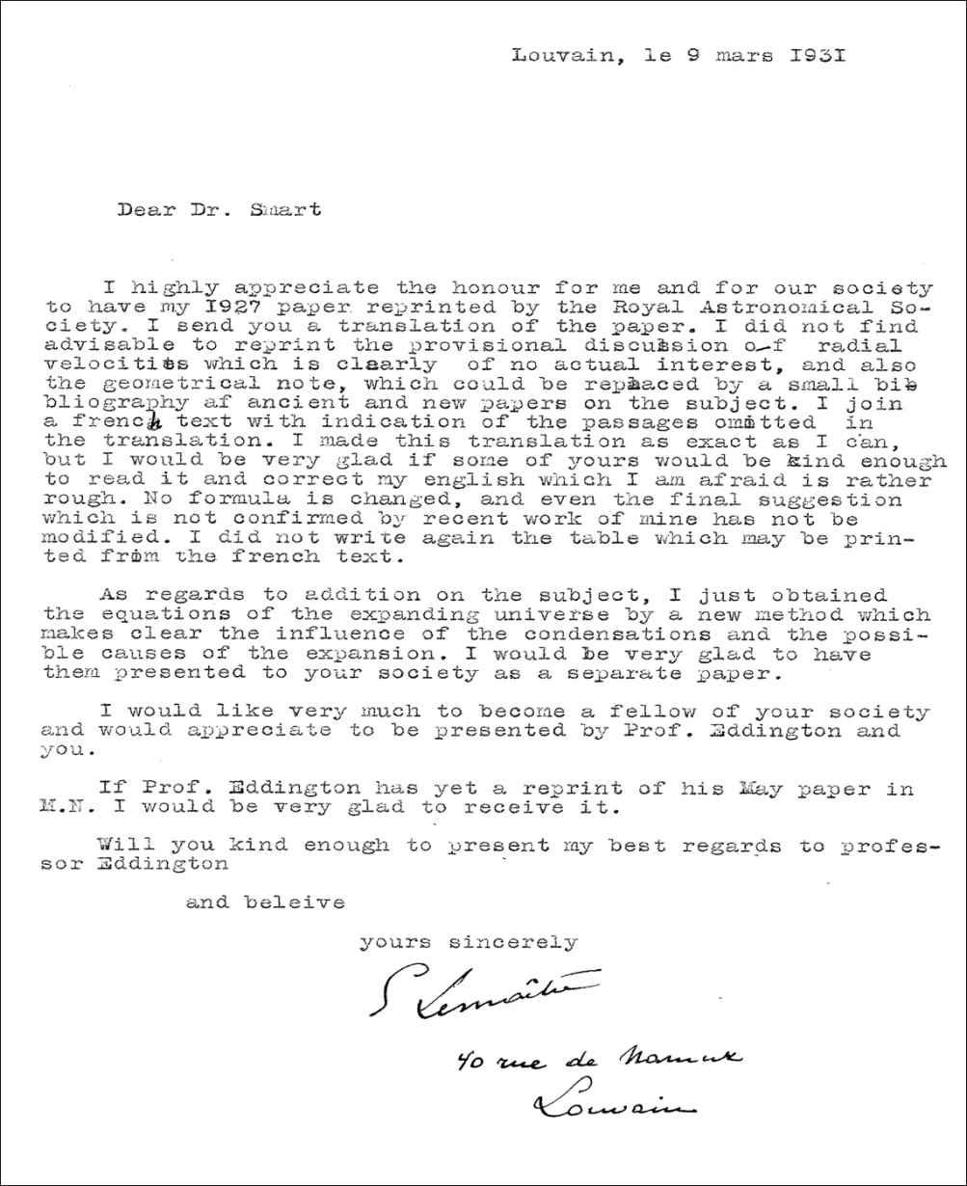

The second piece of evidence was Lemaître’s response to Smart’s letter (figure 27), dated March 9, 1931. The letter reads:

Figure 26a

Figure 26b

Dear Dr. Smart

I highly appreciate the honour for me and for our society to have my 1927 paper reprinted by the Royal Astronomical Society.

I send you a translation of the paper. I did not find advisable to reprint the provisional discussion of radial velocities which is clearly of no actual interest

[Lemaître almost certainly was translating the French word

actuel,

which means “current”],

and also the geometrical note, which could be replaced by a small bibliography of ancient [old] and new papers on the subject

[emphasis added]. I join a french text with indication of the passages omitted in the translation. I made this translation as exact as I can, but I would be very glad if some of yours would be kind enough to read it and correct my english which I am afraid is rather rough. No formula is changed, and even the final suggestion which is not confirmed by recent work of mine has not be modified. I did not write again the table which may be printed from the french text.

As regards to addition on the subject, I just obtained the equations of

the expanding universe by a new method which makes clear the influence of the condensations and the possible causes of the expansion. I would be very glad to have them presented to your society as a separate paper.

I would like very much to become a fellow of your society and would appreciate to be presented by Prof. Eddington and you.

If Prof. Eddington has yet a reprint of his May paper in M.N. I would be very glad to receive it.

Will you be kind enough to present my best regards to professor Eddington.

This clearly puts to bed all the speculations about who translated the paper and who deleted the paragraphs: Lemaître himself did both!

Figure 27

Lemaître’s letter also provides a fascinating insight into the scientific psychology of (at least some of) the scientists of the 1920s. Lemaître was not at all obsessed with establishing priority for his original discovery. Given that Hubble’s results had already been published in 1929, he saw no point in repeating his more tentative earlier findings again in 1931. Rather, he preferred to move forward and to publish his new

paper, “The Expanding Universe,” which he did. Lemaître’s request to join the Royal Astronomical Society was also granted eventually. Lemaître was officially elected as an associate on May 12, 1939.

The Steady State Universe

Returning now to Gold’s provocative question “What if the universe is like that?”—referring to the circular plot of the film

Dead of the Night

—the possibility was not considered palatable by his two colleagues; at least not initially. Hoyle immediately brushed off Gold, scoffing, “Ach, we shall disprove this before dinner.” This “prediction,” however, turned out to be wrong. In Bondi’s words, “

Dinner was a little late that night, and before very long we all said that this was a perfectly possible solution.” In other words, a never-changing universe, with no beginning and no end, started to look more and more attractive. From that point on, however, Hoyle took a somewhat different approach to the problem from that of his scientific peers.

The outlook of Bondi and Gold was based on an appealing philosophical concept. If the universe is indeed evolving and changing, they argued, then there is no clear reason why we should trust that the laws of nature have permanent validity. After all, those laws were established based on experiments performed here and now. In addition, Bondi and Gold perceived that the cosmological principle, as originally stated, presented yet another difficulty. It assumed that observers located in different galaxies anywhere in the universe would all discern the same large-scale picture of the cosmos. But if the universe is continuously evolving with time, this required that the different observers would compare their notes at the same time, which implied that one needed to define what precisely is meant by “at the same time.” To circumvent all of these obstacles,

Bondi and Gold proposed their Perfect Cosmological Principle, which added to the original principle the requirement that there is no preferred time in the cosmos—the universe looks the same from every point

at all times.

Even though Hoyle decided to take a different route, he did find this intuitive principle of Bondi and Gold compelling, especially since it also solved another problem inferred from the observations of the expanding universe. Hubble’s determination of the rate of expansion (which was later found to be wrong) implied a nightmarish scenario in which the universe was only 1.2 billion years old—far less than the estimated age of the Earth! So in spite of Hubble’s enormous prestige (“more than life sized in the 30s and 40s” according to Bondi), Hoyle, Bondi, and Gold felt that another solution had to be found. Unlike Bondi and Gold, however,

Hoyle embarked on a more mathematical, rather than philosophical, approach. In particular, he developed his theory in the framework of Einstein’s general relativity. He started from the observational fact that the universe is expanding. This immediately raised a question: If galaxies are continuously rushing away from each other, does that mean that space is becoming more and more empty? Hoyle answered with a categorical no. Instead, he proposed, matter is continually being created throughout space so that new galaxies and clusters of galaxies are constantly being formed at a rate that compensates precisely for the dilution caused by the cosmic expansion. In this way, Hoyle reasoned, the universe is preserved in a steady state. He once commented wittily, “Things are the way they are because they were the way they were.” The difference between the steady state universe and the evolving (big bang) universe is shown schematically in figure 28, where I have again used the analogy of the inflating sphere. In both cases, we start (at the top) with a sample of the universe, in which the galaxies are represented by small round chads. In the evolutionary scenario (on the left), after some time has passed, the galaxies have receded from one another (bottom left), reducing the overall density of matter. In the steady state scenario, new galaxies have been created, so that the average density remained the same (bottom right).