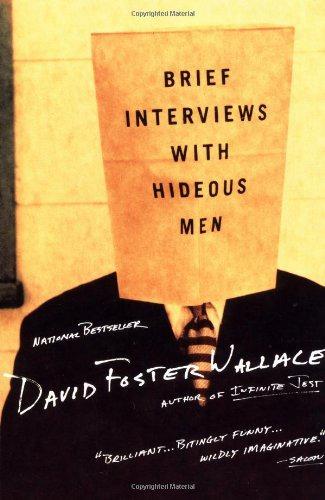

Brief Interviews With Hideous Men

Read Brief Interviews With Hideous Men Online

Authors: David Foster Wallace

ALSO BY

D

AVID

F

OSTER

W

ALLACE

T

HE

B

ROOM OF THE

S

YSTEM

G

IRL WITH

C

URIOUS

H

AIR

I

NFINITE

J

EST

A S

UPPOSEDLY

F

UN

T

HING

I’

LL

N

EVER

D

O

A

GAIN

Copyright © 1999 by David Foster Wallace

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

First eBook Edition: September 2009

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Author herewith acknowledges the generous and broad-minded support of

The Lannan Foundation

The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

The Paris Review

The Staff and Management of Denny’s 24-Hour Family Restaurant, Bloomington IL

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Acknowledgment is made to the following publications in which various forms of this book’s pieces first appeared:

Between C&D, Conjunctions, Esquire, Fiction International, Grand Street, Harper’s,

Houghton Mifflin’s

Best American Short Stories 1992, Mid-American Review, New York Times Magazine, Open City, The Paris Review, Ploughshares, Private Arts, Santa Monica Review, spelunker flophouse,

and

Tin House.

ISBN: 978-0-316-08689-9

For Beth-Ellen Siciliano and Alice R. Dall, hideous ears

sine pari.

Contents

A Radically Condensed History of Postindustrial Life

Brief Interviews with Hideous Men

Yet Another Example of the Porousness of Certain Borders (XI)

Brief Interviews with Hideous Men

Yet Another Example of the Porousness of Certain Borders (VI)

Brief Interviews with Hideous Men

Tri-Stan: I Sold Sissee Nar to Ecko

Brief Interviews with Hideous Men

Yet Another Example of the Porousness of Certain Borders (XXIV)

A RADICALLY CONDENSED HISTORY OF POSTINDUSTRIAL LIFE

When they were introduced, he made a witticism, hoping to be liked. She laughed extremely hard, hoping to be liked. Then each drove home alone, staring straight ahead, with the very same twist to their faces.

The man who’d introduced them didn’t much like either of them, though he acted as if he did, anxious as he was to preserve good relations at all times. One never knew, after all, now did one now did one now did one.

The fifty-six-year-old American poet, a Nobel Laureate, a poet known in American literary circles as ‘the poet’s poet’ or sometimes simply ‘the Poet,’ lay outside on the deck, bare-chested, moderately overweight, in a partially reclined deck chair, in the sun, reading, half supine, moderately but not severely overweight, winner of two National Book Awards, a National Book Critics Circle Award, a Lamont Prize, two grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, a Prix de Rome, a Lannan Foundation Fellowship, a MacDowell Medal, and a Mildred and Harold Strauss Living Award from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, a president emeritus of PEN, a poet two separate American generations have hailed as the voice of their generation, now fifty-six, lying in an unwet XL Speedo-brand swimsuit in an incrementally reclinable canvas deck chair on the tile deck beside the home’s pool, a poet who was among the first ten Americans to receive a ‘Genius Grant’ from the prestigious John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, one of only three American recipients of the Nobel Prize for Literature now living, 5'8'', 181 lbs., brown/brown, hairline unevenly recessed because of the inconsistent acceptance/rejection of various Hair Augmentation Systems– brand transplants, he sat, or lay—or perhaps most accurately just ‘reclined’—in a black Speedo swimsuit by the home’s kidney-shaped pool,

1

on the pool’s tile deck, in a portable deck chair whose back was now reclined four clicks to an angle of 35° w/r/t the deck’s mosaic tile, at 10:20

A.M.

on 15 May 1995, the fourth most anthologized poet in the history of American belles lettres, near an umbrella but not in the actual shade of the umbrella, reading

Newsweek

magazine,

2

using the modest swell of his abdomen as an angled support for the magazine, also wearing thongs, one hand behind his head, the other hand out to the side and trailing on the dun-and-ochre filigree of the deck’s expensive Spanish ceramic tile, occasionally wetting a finger to turn the page, wearing prescription sunglasses whose lenses were chemically treated to darken in fractional proportion to the luminous intensity of the light to which they were exposed, wearing on the trailing hand a wristwatch of middling quality and expense, simulated-rubber thongs on his feet, legs crossed at the ankle and knees slightly spread, the sky cloudless and brightening as the morning’s sun moved up and right, wetting a finger not with saliva or perspiration but with the condensation on the slender frosted glass of iced tea that rested now just on the border of his body’s shadow to the chair’s upper left and would have to be moved to remain in that cool shadow, tracing a finger idly down the glass’s side before bringing the moist finger idly up to the page, occasionally turning the pages of the 19 September 1994 edition of

Newsweek

magazine, reading about American health-care reform and about USAir’s tragic Flight 427, reading a summary and favorable review of the popular nonfiction volumes

Hot Zone

and

The Coming Plague

, sometimes turning several pages in succession, skimming certain articles and summaries, an eminent American poet now four months short of his fifty-seventh birthday, a poet whom

Newsweek

magazine’s chief competitor,

Time

, had once rather absurdly called ‘the closest thing to a genuine literary immortal now living,’ his shins nearly hairless, the open umbrella’s elliptic shadow tightening slightly, the thongs’ simulated rubber pebbled on both sides of the sole, the poet’s forehead dotted with perspiration, his tan deep and rich, the insides of his upper legs nearly hairless, his penis curled tightly on itself inside the tight swimsuit, his Vandyke neatly trimmed, an ashtray on the iron table, not drinking his iced tea, occasionally clearing his throat, at intervals shifting slightly in the pastel deck chair to scratch idly at the instep of one foot with the big toe of the other foot without removing his thongs or looking at either foot, seemingly intent on the magazine, the blue pool to his right and the home’s thick glass sliding rear door to his oblique left, between himself and the pool a round table of white woven iron impaled at the center by a large beach umbrella whose shadow now no longer touches the pool, an indisputably accomplished poet, reading his magazine in his chair on his deck by his pool behind his home. The home’s pool and deck area is surrounded on three sides by trees and shrubbery. The trees and shrubbery, installed years before, are densely interwoven and tangled and serve the same essential function as a redwood privacy fence or a wall of fine stone. It is the height of spring, and the trees and shrubbery are in full leaf and are intensely green and still, and are complexly shadowed, and the sky is wholly blue and still, so that the whole enclosed tableau of pool and deck and poet and chair and table and trees and home’s rear façade is very still and composed and very nearly wholly silent, the soft gurgle of the pool’s pump and drain and the occasional sound of the poet clearing his throat or turning the pages of

Newsweek

magazine the only sounds—not a bird, no distant lawn mowers or hedge trimmers or weed-eating devices, no jets overhead or distant muffled sounds from the pools of the homes on either side of the poet’s home—nothing but the pool’s respiration and poet’s occasional cleared throat, wholly still and composed and enclosed, not even a hint of a breeze to stir the leaves of the trees and shrubbery, the silent living enclosing flora’s motionless green vivid and inescapable and not like anything else in the world in either appearance or suggestion.

3

Happy Birthday. Your thirteenth is important. Maybe your first really public day. Your thirteenth is the chance for people to recognize that important things are happening to you.

Things have been happening to you for the past half year. You have seven hairs in your left armpit now. Twelve in your right. Hard dangerous spirals of brittle black hair. Crunchy, animal hair. There are now more of the hard curled hairs around your privates than you can count without losing track. Other things. Your voice is rich and scratchy and moves between octaves without any warning. Your face has begun to get shiny when you don’t wash it. And two weeks of a deep and frightening ache this past spring left you with something dropped down from inside: your sack is now full and vulnerable, a commodity to be protected. Hefted and strapped in tight supporters that stripe your buttocks red. You have grown into a new fragility.

And dreams. For months there have been dreams like nothing before: moist and busy and distant, full of yielding curves, frantic pistons, warmth and a great falling; and you have awakened through fluttering lids to a rush and a gush and a toe-curling scalp-snapping jolt of feeling from an inside deeper than you knew you had, spasms of a deep sweet hurt, the streetlights through your window blinds cracking into sharp stars against the black bedroom ceiling, and on you a dense white jam that lisps between legs, trickles and sticks, cools on you, hardens and clears until there is nothing but gnarled knots of pale solid animal hair in the morning shower, and in the wet tangle a clean sweet smell you can’t believe comes from anything you made inside you.

* * *

The smell is, more than anything, like this swimming pool: a bleached sweet salt, a flower with chemical petals. The pool has a strong clear blue smell, though you know the smell is never as strong when you are actually in the blue water, as you are now, all swum out, resting back along the shallow end, the hip-high water lapping at where it’s all changed.

Around the deck of this old public pool on the western edge of Tucson is a Cyclone fence the color of pewter, decorated with a bright tangle of locked bicycles. Beyond this a hot black parking lot full of white lines and glittering cars. A dull field of dry grass and hard weeds, old dandelions’ downy heads exploding and snowing up in a rising wind. And past all this, reddened by a round slow September sun, are mountains, jagged, their tops’ sharp angles darkening into definition against a deep red tired light. Against the red their sharp connected tops form a spiked line, an EKG of the dying day.

The clouds are taking on color by the rim of the sky. The water is spangles off soft blue, five-o’clock warm, and the pool’s smell, like the other smell, connects with a chemical haze inside you, an interior dimness that bends light to its own ends, softens the difference between what leaves off and what begins.

Your party is tonight. This afternoon, on your birthday, you have asked to come to the pool. You wanted to come alone, but a birthday is a family day, your family wants to be with you. This is nice, and you can’t talk about why you wanted to come alone, and really truly maybe you didn’t want to come alone, so they are here. Sunning. Both your parents sun. Their deck chairs have been marking time all afternoon, rotating, tracking the sun’s curve across a desert sky heated to an eggy film. Your sister plays Marco Polo near you in the shallows with a group of thin girls from her grade. She is being blind now, her Marco’s being Polo’d. She is shut-eyed and twirling to different cries, spinning at the hub of a wheel of shrill girls in bathing caps. Her cap has raised rubber flowers. There are limp old pink petals that shake as she lunges at blind sound.

There at the other end of the pool is the diving tank and the high board’s tower. Back on the deck behind is the SN CK BAR, and on either side, bolted above the cement entrances to dark wet showers and lockers, are gray metal bullhorn speakers that send out the pool’s radio music, the jangle flat and tinny thin.

Your family likes you. You are bright and quiet, respectful to elders—though you are not without spine. You are largely good. You look out for your little sister. You are her ally. You were six when she was zero and you had the mumps when they brought her home in a very soft yellow blanket; you kissed her hello on her feet out of concern that she not catch your mumps. Your parents say that this augured well. That it set the tone. They now feel they were right. In all things they are proud of you, satisfied, and they have retreated to the warm distance from which pride and satisfaction travel. You all get along well.

Happy Birthday. It is a big day, big as the roof of the whole southwest sky. You have thought it over. There is the high board. They will want to leave soon. Climb out and do the thing.

Shake off the blue clean. You’re half-bleached, loose and soft, tenderized, pads of fingers wrinkled. The mist of the pool’s too-clean smell is in your eyes; it breaks light into gentle color. Knock your head with the heel of your hand. One side has a flabby echo. Cock your head to the side and hop—sudden heat in your ear, delicious, and brain-warmed water turns cold on the nautilus of your ear’s outside. You can hear harder tinnier music, closer shouts, much movement in much water.

The pool is crowded for this late. Here are thin children, hairy animal men. Disproportionate boys, all necks and legs and knobby joints, shallow-chested, vaguely birdlike. Like you. Here are old people moving tentatively through shallows on stick legs, feeling at the water with their hands, out of every element at once.

And girl-women, women, curved like instruments or fruit, skin burnished brown-bright, suit tops held by delicate knots of fragile colored string against the pull of mysterious weights, suit bottoms riding low over the gentle juts of hips totally unlike your own, immoderate swells and swivels that melt in light into a surrounding space that cups and accommodates the soft curves as things precious. You almost understand.

The pool is a system of movement. Here now there are: laps, splash fights, dives, corner tag, cannonballs, Sharks and Minnows, high fallings, Marco Polo (your sister still It, halfway to tears, too long to be It, the game teetering on the edge of cruelty, not your business to save or embarrass). Two clean little bright-white boys caped in cotton towels run along the poolside until the guard stops them dead with a shout through his bullhorn. The guard is brown as a tree, blond hair in a vertical line on his stomach, his head in a jungle explorer hat, his nose a white triangle of cream. A girl has an arm around a leg of his little tower. He’s bored.

Get out now and go past your parents, who are sunning and reading, not looking up. Forget your towel. Stopping for the towel means talking and talking means thinking. You have decided being scared is caused mostly by thinking. Go right by, toward the tank at the deep end. Over the tank is a great iron tower of dirty white. A board protrudes from the top of the tower like a tongue. The pool’s concrete deck is rough and hot against your bleached feet. Each of your footprints is thinner and fainter. Each shrinks behind you on the hot stone and disappears.

Lines of plastic wieners bob around the tank, which is entirely its own thing, empty of the rest of the pool’s convulsive ballet of heads and arms. The tank is blue as energy, small and deep and perfectly square, flanked by lap lanes and SN CK BAR and rough hot deck and the bent late shadow of the tower and board. The tank is quiet and still and healed smooth between fallings.

There is a rhythm to it. Like breathing. Like a machine. The line for the board curves back from the tower’s ladder. The line moves in its curve, straightens as it nears the ladder. One by one, people reach the ladder and climb. One by one, spaced by the beat of hearts, they reach the tongue of the board at the top. And once on the board, they pause, each exactly the same tiny heartbeat pause. And their legs take them to the end, where they all give the same sort of stomping hop, arms curving out as if to describe something circular, total; they come down heavy on the edge of the board and make it throw them up and out.

It’s a swooping machine, lines of stuttered movement in a sweet late bleach mist. You can watch from the deck as they hit the cold blue sheet of the tank. Each fall makes a white that plumes and falls into itself and spreads and fizzes. Then blue clean comes up in the middle of the white and spreads like pudding, making it all new. The tank heals itself. Three times as you go by.

You are in line. Look around. Look bored. Few talk in the line. Everyone seems by himself. Most look at the ladder, look bored. You almost all have crossed arms, chilled by a late dry rising wind on the constellations of blue-clean chlorine beads that cover your backs and shoulders. It seems impossible that everybody could really be this bored. Beside you is the edge of the tower’s shadow, the tilted black tongue of the board’s image. The system of shadow is huge, long, off to the side, joined to the tower’s base at a sharp late angle.

Almost everyone in line for the board watches the ladder. Older boys watch older girls’ bottoms as they go up. The bottoms are in soft thin cloth, tight nylon stretch. The good bottoms move up the ladder like pendulums in liquid, a gentle uncrackable code. The girls’ legs make you think of deer. Look bored.

Look out past it. Look across. You can see so well. Your mother is in her deck chair, reading, squinting, her face tilted up to get light on her cheeks. She hasn’t looked to see where you are. She sips something sweet out of a bright can. Your father is on his big stomach, back like the hint of a hump of a whale, shoulders curling with animal spirals, skin oiled and soaked red-brown with too much sun. Your towel is hanging off your chair and a corner of the cloth now moves—your mother hit it as she waved away a sweat bee that likes what she has in the can. The bee is back right away, seeming to hang motionless over the can in a sweet blur. Your towel is one big face of Yogi Bear.

At some point there has gotten to be more line behind you than in front of you. Now no one in front except three on the slender ladder. The woman right before you is on the low rungs, looking up, wearing a tight black nylon suit that is all one piece. She climbs. From above there is a rumble, then a great falling, then a plume and the tank reheals. Now two on the ladder. The pool rules say one on the ladder at a time, but the guard never shouts about it. The guard makes the real rules by shouting or not shouting.

This woman above you should not wear a suit as tight as the suit she is wearing. She is as old as your mother, and as big. She is too big and too white. Her suit is full of her. The backs of her thighs are squeezed by the suit and look like cheese. Her legs have abrupt little squiggles of cold blue shattered vein under the white skin, as if something were broken, hurt, in her legs. Her legs look like they hurt to be squeezed, full of curled Arabic lines of cold broken blue. Her legs make you feel like your own legs hurt.

The rungs are very thin. It’s unexpected. Thin round iron rungs laced in slick wet Safe-T felt. You taste metal from the smell of wet iron in shadow. Each rung presses into the bottoms of your feet and dents them. The dents feel deep and they hurt. You feel heavy. How the big woman over you must feel. The handrails along the ladder’s sides are also very thin. It’s like you might not hold on. You’ve got to hope the woman holds on, too. And of course it looked like fewer rungs from far away. You are not stupid.

Get halfway up, up in the open, big woman placed above you, a solid bald muscular man on the ladder underneath your feet. The board is still high overhead, invisible from here. But it rumbles and makes a heavy flapping sound, and a boy you can see for a few contained feet through the thin rungs falls in a flash of a line, a knee held to his chest, doing a splasher. There is a huge exclamation point of foam up into your field of sight, then scattered claps into a great fizzing. Then the silent sound of the tank healing to new blue all over again.

More thin rungs. Hold on tight. The radio is loudest here, one speaker at ear-level over a concrete locker room entrance. A cool dank whiff of the locker room inside. Grab the iron bars tight and twist and look down behind you and you can see people buying snacks and refreshments below. You can see down into it: the clean white top of the vendor’s cap, tubs of ice cream, steaming brass freezers, scuba tanks of soft drink syrup, snakes of soda hose, bulging boxes of salty popcorn kept hot in the sun. Now that you’re overhead you can see the whole thing.

There’s wind. It’s windier the higher you get. The wind is thin; through the shadow it’s cold on your wet skin. On the ladder in the shadow your skin looks very white. The wind makes a thin whistle in your ears. Four more rungs to the top of the tower. The rungs hurt your feet. They are thin and let you know just how much you weigh. You have real weight on the ladder. The ground wants you back.

Now you can see just over the top of the ladder. You can see the board. The woman is there. There are two ridges of red, hurt-looking callus on the backs of her ankles. She stands at the start of the board, your eyes on her ankles. Now you’re up above the tower’s shadow. The solid man under you is looking through the rungs into the contained space the woman’s fall will pass through.

She pauses for just that beat of a pause. There’s nothing slow about it at all. It makes you cold. In no time she’s at the end of the board, up, down on it, it bends low like it doesn’t want her. Then it nods and flaps and throws her violently up and out, her arms opening out to inscribe that circle, and gone. She disappears in a dark blink. And there’s time before you hear the hit below.

Listen. It does not seem good, the way she disappears into a time that passes before she sounds. Like a stone down a well. But you think she did not think so. She was part of a rhythm that excludes thinking. And now you have made yourself part of it, too. The rhythm seems blind. Like ants. Like a machine.

You decide this needs to be thought about. It may, after all, be all right to do something scary without thinking, but not when the scariness is the not thinking itself. Not when not thinking turns out to be wrong. At some point the wrongnesses have piled up blind: pretend-boredom, weight, thin rungs, hurt feet, space cut into laddered parts that melt together only in a disappearance that takes time. The wind on the ladder not what anyone would have expected. The way the board protrudes from shadow into light and you can’t see past the end. When it all turns out to be different you should get to think. It should be required.