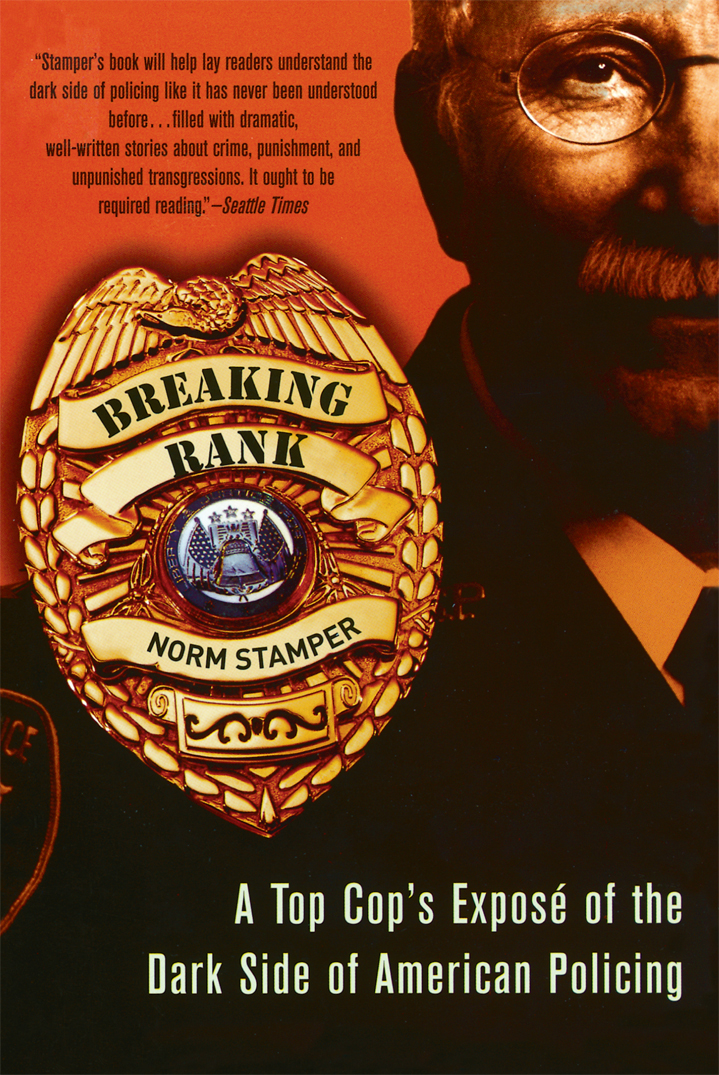

Breaking Rank

Authors: Norm Stamper

For James Norman Stamper, Everett Eugene Stamper, and Matthew Todd Stamper

B

REAKING

R

ANK

A Top Cop's Exposé of the

Dark Side of American Policing

Published by

Nation Books

An Imprint of Avalon Publishing Group

245 West 17th Street, 11th Floor

New York, NY 10011

Copyright © 2005 by Norm Stamper

Nation Books is a co-publishing venture of the Nation Institute and Avalon Publishing Group Incorporated.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

This memoir is a product of the author's recollections and is thus rendered as a subjective accounting of events that occurred in his/her life.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN-13: 978-0-78673-624-9

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Book design by Maria E. Torres

Distributed by Publishers Group West

CONTENTS

1 ⢠An Open Letter to a Bad Cop

2 ⢠Wage War on Crime, Not Drugs

3 ⢠Prostitution: Get a Room!

4 ⢠Capital Punishment: The Coward's Way Out

5 ⢠Criminals' Rights: Worth Protecting?

8 ⢠Why White Cops Kill Black Men

11 ⢠Sexual Predators in Uniform

12 ⢠The Blue Wall of Silence

13 ⢠The Police Image: Sometimes a Gun Is Just a Gun

14 ⢠It's Not All Cops and Robbers

15 ⢠Doughnuts, Tacos, and Fat Cops

16 ⢠Demilitarizing the Police

18 ⢠Staying Alive in a World of Sudden, Violent Death

20 ⢠Treating Cops Like Kids: Police Discipline

21 ⢠A Dark Take on Financial Liability

22 ⢠Up With Labor, (Not so Fast, Police Unions)

25 ⢠Egos on Patrol: Giuliani vs. Bratton

26 ⢠Marching for Dykes on Bikes (and Against Jesus)

27 ⢠The Fourth Estate: A Chief's Lament

28 ⢠Snookered in Seattle: The WTO Riots

29 ⢠Community Policing: A Radical View

30 ⢠Cultivating Fearless Leadership

W

HAT DO YOU SEE

when you picture a “safe” America? I envision infants born into a loving, nurturing worldâto women whose reproductive rights are protected by law. Children and teens who exhibit consideration for themselves and others. Citizens who question, challenge, and disagree with one anotherânonviolently. Men who refuse to abuse women. Gun violence gone from our homes and streets, our schools and workplaces. Law enforcers, from the beat cop to the U.S. Attorney General doing their jobs properly, applying their imagination, playing by the rules. I see Americans, black, white, straight, gay, expressing themselves freely, pursuing happiness as they define it. I picture an America safe from consumer, environmental, and political, as well as predatory crimeâand free from the specter of an overzealous, overreaching, moralistic government.

Einstein defined insanity as doing the same thing over and over, and expecting different results. That pretty much sums up this nation's law enforcement approach to public safety. Take drugs, for example. How much more evidence do we need that America has

lost

its “war on drugs,” even as we keep our cops slogging away on the perilous front lines? Or prostitution: How likely is it that hookers and their johns will decamp the sex industry any time soon? Or guns: I heard Barry Goldwater rail against controls some 35 years ago because “it would take 50 years to get rid of handguns.” Or

men

: What are the chances that we American males will accept full responsibility for the breathtaking levels of violence in our society, and

do

something about it? Or racist cops: Do we honestly believe we've seen the last Rodney King, Abner Louima, Amadou Diallo incident?

Problems like these

can

be solved. It's possible for a police force to be tough on crime and still treat people with dignity and respect. But not with the same politics, the same paramilitary infrastructure, and the same inbred cop culture that

produce

police incompetence and misconduct. What's needed is an honest examination of the failures of our justice system, along

with the will and the courage to employ radically differentâbut theoretically soundâapproaches to their solution.

How? By

breaking rank,

by questioning long-accepted ways of doing business, and by taking direct action to change the system.

I had impressions of the law and “lawmen” long before I became a cop. As a kid, I was in some kind of trouble just about every day of my life. Most of my behavioral problems were handled not by the police but by my parents (unevenly), or by teachers and coaches (more constructively, on the whole). Still, despite an anemic rap sheet I had enough early contact with “the Man” to cultivate some major hostility toward the police.

I grew up in National City, a small town of car lots, slaughter-houses, meat packing plants, and navy bars at the southern city limits of San Diego, 14 miles from the Tijuana border.

At nine, I had my first contact with two of NCPD's finest. My friend Gary and I, weary of shooting out streetlights with our slingshots, meandered over to Kimball Park to kick over the portable Little League fence, again. We'd finished off about a third of the job when a black-and-white Dodge shot out from behind the visitors' dugout and swooped down on us from the left field foul line. One of them seized the cigarettes I'd lifted from my mother. The driver cop, the talker, ordered us to put out our smokes and replace the fence. The two men sat in their car, supervising us, tiny orange dots lighting up their faces as they inhaled mom's Chesterfields. When we finished, the talker ordered us, with great profanity, never to set foot in the park again. I had to agree with my pal when he said, as the black-and-white drove off, leaving us in a cloud of dust, “I

hate

those fuckers!”

When I was sixteen a National City cop wrote me a citation for doing seventeen miles an hour through a fifteen-mile-an-hour intersection. (Later, I would learn the technical term for such a ticket:

chickenshit

.)

A year later I watched a San Diego police officer jab his finger into the chest of the lead singer of our R&B band and call him a “splib” and a “motherfucking nigger.”

In my late teens I sat glued to the tube as Birmingham Bull Connor sicced his dogs on peacefully assembled civil rights demonstrators. I saw well-dressed Negroesâwomen in Sunday frocks, men in white shirts, skinny ties, and porkpie hats, even childrenâget clubbed to the ground, kicked, bitten by police dogs, and sprayed with fire hoses. It felt like

I'd

been kicked in the stomach.

At nineteen and twenty I was burglarized, three times. The police took forever to show up, and when they did the one in a suit mumbled something about the “Mezicans” who lived up the steep bank from my apartment. They took no prints, no shoe impressions, not even notes. They arrested no one, recovered none of the hundred or so jazz and R&B LPs that were my most prized possessions. (To this day I still feel the sting of that loss, along with a powerful case of resentment. Not so much toward the burglarsâthey did

their

job.)

And where were the cops when my old man was beating the snot out of his sons? Our house at 2324 K Avenue was the site of multiple and continuing felonious acts. But even if they'd been called (our neighbors certainly heard what was going on) the cops wouldn't have done a thing.

People talk about “bad apples” in police work. To me the whole barrel was moldy. Not once, growing up, did I have a positive contact with a police officer. I'm not claiming I was an angel, not saying my behavior didn't contribute to my “anti-police” attitude. It's just that I got neither protection nor service from my local police. All I got was no respect.

So why did I become one of them? I needed a job.