Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (9 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

Rhau-Grunenberg was lured to Wittenberg from Erfurt, where he had worked in the printing house of Wolf Sturmer. He was not an uneducated man, and had evidently attained some sort of university qualification.

22

It was probably this that brought him to the attention of Staupitz, who persuaded him to leave Sturmer and take up the vacant position of university printer in Wittenberg. The university did everything in its power to smooth his path. Rhau-Grunenberg was furnished with the printing materials left by Marschalk and Trebelius, and provided with a workshop and residential space on university property. In 1512 he moved into new quarters close to the Augustinian house, where he would have been a near neighbor of Martin Luther.

Over the years Luther developed very mixed feelings about Rhau-Grunenberg. He recognized that he was pious and well-intentioned. In the difficult years after 1517 Rhau-Grunenberg would offer Luther unwavering support, and this was the sort of loyalty that Luther felt a duty to repay. But fondness was often balanced by exasperation. Rhau-Grunenberg was notoriously slow, and in the furious pamphlet exchanges that followed the indulgence controversy, that put Luther at a real disadvantage. His work was also functional and unimaginative. This might have been passable for a student who required a cheap broadsheet or pamphlet for a necessary academic examination, but it was painful to someone of Luther’s refined aesthetic sensibilities.

In September 1516 Luther reported to Spalatin that faculty colleagues wanted him to publish his lecture notes on the Psalms; they were suggesting he give them to Rhau-Grunenberg. Luther was not keen to surrender this work to the press at this point, but at least if they went to Rhau-Grunenberg, he wrote, the work would be nothing fancy, because they would then be printed in a rougher typeface.

23

This may seem a little grand and lofty from someone who to that point had published virtually nothing, and he would indeed entrust his first work, his modest introduction to sections of Johannes Tauler’s mystical work, the

Theologia Deutsch,

to Rhau-Grunenberg in this same year.

24

But you only have to examine a sample of Rhau-Grunenberg’s work to realize that Luther had a point. Take a typical early product of his press, an oration given by Filippo Beroaldo.

25

The book was a small quarto of twenty-four leaves, a steady week’s work for a well-managed press. The text is presented as an undifferentiated mass in a medium Roman type. There are no decorated initials; rather, the first capital is a small character in the same font used for the rest of the text, set in a space that would normally be assigned to a woodblock initial (as if, as in the first years of print, it would subsequently be painted over by an illuminator). The text is poorly aligned and heavily abbreviated. Rudimentary side notes cling awkwardly to the text body. The title page is two simple lines in the same text type, again in a style more reminiscent of the 1470s. It is as if the intervening forty years of title-page development had simply not taken place.

26

This was published in 1508, shortly after Rhau-Grunenberg arrived in Wittenberg, but the next ten years registered no substantial improvement. This in itself was unusual, because printers learned their craft and improved the quality of their work by studying and adopting features they found in other books. By this point there were circulating in Wittenberg plenty of books printed in Europe’s leading centers of typographical design, as we will see when we examine the university library. But Rhau-Grunenberg seemed content just to plod along. As the proprietor of the only press in Wittenberg, he could rely on at least a modicum of work from the university to keep his press active.

Yet only up to a point: for the more status conscious of the faculty, Rhau-Grunenberg’s work was not of an acceptable standard. The most telling judgment on the quality of Wittenberg printing in these years can be found in the number of those associated with the university who looked elsewhere when they had texts to put to the press. Christoph Scheurl was in every other respect a passionate advocate of Wittenberg, but he would not consign his works to the rude attentions of Rhau-Grunenberg. A second edition of the Bologna laudation published after his arrival in Wittenberg was instead dispatched to Martin Landsberg in Leipzig.

27

A series of orations given in Wittenberg by Scheurl and others was also sent to Landsberg for publication, a round trip for manuscript and printed copies of almost a hundred miles.

28

In November 1508 Scheurl gave an oration in honor of two recently promoted scholars, which begins with a long dedication to Lucas Cranach, Wittenberg’s most distinguished artistic adornment. It continued with praise of the elector, before embarking on a long and fulsome description of the glories of Wittenberg and its castle church. Yet even this (perhaps especially this) could not be entrusted to the local printer.

29

Most incongruous of all was the use of Landsberg for Andreas Meinhardi’s promotional dialog extolling the virtues of Wittenberg and its new university: a new Rome, perhaps, but not in its printing culture.

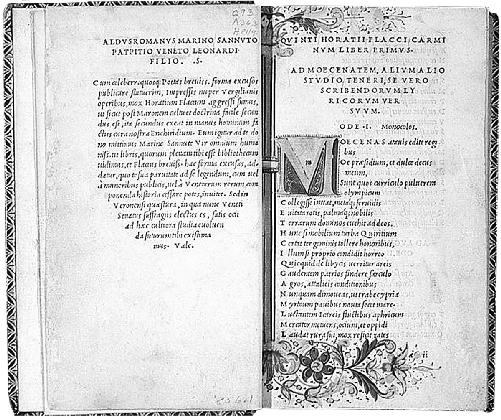

A

LDUS

M

ANUTIUS,

H

ORACE (1501)

Aldines were the benchmark of quality for any sixteenth-century collector who aspired to build a library. The contrast with the quality of locally produced books would have been telling and obvious.

During these years the elector was assembling his own distinguished book collection. In 1512 this would be made over to the university, for the use of its scholars and students. Georg Spalatin was entrusted with the task of enhancing the collection, and considerable sums were made available for this purpose.

30

It almost goes without saying that none of the books Spalatin wished to acquire were printed locally. Spalatin sought out the best editions, published in the most distinguished print shops all over Europe. Books were purchased from the bookshops of Erfurt, and from the fairs in Leipzig and Frankfurt. In March 1512, emboldened by the elector’s generosity, Spalatin wrote directly to Aldus Manutius in Venice, asking that Manutius send a catalog of his books in print. Aldus was

at this point Europe’s most famous printer, his books (now universally known as Aldines) a benchmark for elegance and editorial rigor. Any aspiring collector wanted to have examples in his library and Frederick was no exception. But securing the books from faraway Venice proved difficult. Spalatin’s inquiry and then a second letter failed to elicit a response, so a third was dispatched, this time signed personally by the elector. This explained the sort of library that Frederick wanted to create, and the important part the products of this famous shop would play in building its reputation. A follow-up letter from Spalatin shrewdly asked Aldus to note with a cross the books in his catalog he kept in stock at his branch office

in Frankfurt, from where they could be more cheaply transported to Wittenberg.

It is rather extraordinary that despite this battery of correspondence it would be March 1514 before Aldus would reply, rather unconvincingly pleading that earlier letters had vanished in the post. The order was placed and the books supplied. The Aldines were the jewel in an increasingly precious collection, a priceless resource to the local professors and a standing rebuke to the quality of the local press. In the circumstances one can perhaps forgive Luther’s frustration at Rhau-Grunenberg’s stolid indifference to aesthetic considerations, turning out the utilitarian works that to the more sophisticated reader screamed provincialism. It was a jarringly discordant note in Frederick’s otherwise highly successful campaign to create a northern cultural capital. Certainly no one handling Rhau-Grunenberg’s rudimentary offerings could ever have imagined Wittenberg’s future as a major print entrepôt.

STRUGGLES

Luther’s return to Wittenberg in 1511 was the result of a shrewd deal between Staupitz and the elector. Luther would take over Staupitz’s chair in Biblical Studies, and Frederick would sponsor the necessary fees for Luther’s promotion to a doctorate.

31

Luther was only twenty-nine years old when he assumed these daunting duties, following in the footsteps of his academic patron. The next five years would be a time of diligent study and significant intellectual development as well as sometimes heated controversy. During this time Luther was every bit as much a student as a teacher: his heartfelt engagement with biblical scholarship can be followed in his two great lecture series in these years, on the Psalms and Paul’s Epistle to the Romans.

Understanding Luther’s state of mind during these important years is to a large extent bedeviled by what comes after. We know that between 1517 and 1520 he would repudiate his church and build, on the

basis of startlingly original biblical premises, a new understanding of man’s relationship with God. Almost from that day to this, theologians have sought to identify the origins of this Reformation breakthrough, the precise moment at which Luther came to the decisive theological insights. Luther’s own contribution to this debate, a brief reminiscence of 1545, is not particularly helpful, as he described a long period of spiritual wrestling leading to a decisive revelation of God’s righteousness: “Now I felt as if I had been born again: the gates had been opened and I had entered Paradise itself.”

32

One can see why toward the end of a dramatic and turbulent life, Luther would choose to see his early spiritual maturity in this way, as strenuous wrestling with obdurate theological problems leading to a decisive moment of revelation. This is certainly a reconstruction that does justice to the momentousness of the eventual consequence for his life, his world, and his church. This narrative of strenuous engagement has become a fixed point in the Luther drama, the period of

Anfechtungen,

struggles, driving the intense young monk almost to the point of despair.

This stress on the struggle through long periods of intense study before Luther reached his central theological insights has one other important function. From the perspective of 1545 Luther sought to differentiate his own spiritual journey from more radical thinkers who, inspired by his scriptural principles, had reached their own surprising revelations of God’s purpose.

33

Luther had now had twenty-five years to regret his too-casual proclamation of a “priesthood of all believers,” as the enthusiasts he would angrily denounce as fanatics presented their own versions of the social gospel. So this retrospective presentation of a Reformation breakthrough balanced two elements, patient study and sudden understanding, with subtle care.

The reality is probably far less dramatic than this carefully constructed narrative would suggest. Through five years of teaching and study, Luther moved beyond a solid grounding in traditional theology toward an exposition of the Christian life based on an intense and continuous engagement with Scripture. The most immediate struggle

of this period was of a rather different nature: a determination, shared with initially doubtful colleagues, to incorporate these new theological insights into the curriculum at Wittenberg. This led to a tense altercation, in which Luther took an increasingly leading role: a dress rehearsal for the controversy that would erupt over indulgences in 1517.

The maturation of Luther’s theological understanding can be divided into two key elements: the turn toward Augustine, and his understanding of the centrality of Scripture. Both can be followed in texts richly annotated in Luther’s own hand. The awakening to Augustine began as early as 1509, while Luther was still in Erfurt. Luther’s thorough study of Augustine’s

City of God

and

De Trinitate

(

On the Trinity

) is revealed by copiously annotated texts now in the Ratsschulbibliothek in Zwickau. From this point on Luther would draw Augustine to the heart of his theological understanding. The result was a revulsion against Aristotle, the Greek scholar whose works dominated both the university curriculum and the Scholastic method; in time, this hostility to Aristotle would become almost pathological.

More immediately Luther had to master new tasks that became progressively more numerous and demanding. In October 1512 he was promoted to Doctor of Theology in a ceremony from which his Erfurt brethren remained ostentatiously absent. Luther had been initially reluctant to assume these responsibilities, and it required all of Staupitz’s eloquence to persuade him. In future years he would have cause to bless his patron’s persistence, as in the controversies with his ecclesiastical superiors after 1517 he frequently referred to his status as a doctor and professor as proof of his competence to debate adversaries in the church hierarchy. His first major lecture series in his professorial role, on the Book of Psalms, began in the autumn of 1513. Luther’s method involved a careful verse-by-verse exposition of each psalm in sequence; for preparation he used a specially prepared Latin edition of the text with wide spaces between the lines, in which he made copious manuscript notes.

34

In 1515, before he began his lecture series on Romans, Luther commissioned Rhau-Grunenberg to produce a similar wide-spaced edition for

his use and that of his students. Luther’s own copy survives in the library at Berlin.

35