Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (8 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

LEUCOREA

When Luther returned to Wittenberg it was understood that he would resume his teaching duties in the university. This represented a considerable opportunity for a man of his intellect, now restlessly searching for a way to apply his rapidly expanding theological knowledge. For the university founded by the determined elector had made a promising beginning; Luther was only one of a number of talented men who had committed themselves to the new institution.

The establishment of a university in Wittenberg was a logical part of Frederick the Wise’s determination to bring distinction to his new capital.

11

The partition of 1485 had placed Saxony’s only university, Leipzig, in the territories of the Ernestine branch. The emperor’s tactful and supportive hint that all of Germany’s electoral territories should have a university only served to confirm Frederick’s determination to create an institution worthy of his status in the Empire. The elector set to with characteristic energy. Offering the university quarters in his new castle complex gave a clear signal of sustained commitment to its success, and Frederick also purchased other properties around the city to serve as lecture theaters and dormitories. In the meantime, the castle church served as its chief teaching space, and the church door as its bulletin board. Here notices of forthcoming academic events, such as disputation theses to be defended, would be posted. The church door must have been crowded with academic paperwork long before Luther published his famous theses against indulgences and affixed them with the rest.

The foundation of the university broke new ground in several respects. It was, in its first years, a secular establishment. Frederick obtained authorization for the new university from the emperor rather than the pope, a charter letter granted by Maximilian in June 1502. It was only five years later that the pope gave his blessing, awarding special privileges to the university that permitted it, usefully, to apply income from the All Saints Church to university purposes.

12

The new institution also proposed a clear and relatively daring intellectual agenda. The letter of invitation to the grand opening on October 18, 1502, written unusually in German, announced that the new university, besides traditional subjects, would also teach the humanities. The commitment to the new humanist learning was symbolized by the adoption of the name Leucorea, from the Greek for white and mountain.

These eye-catching statements attracted a great deal of interest among German scholars. The poet Hermann von dem Busche traveled to Wittenberg to perform the opening oration, and several other

luminous figures accepted positions on the faculty. Johann von Staupitz was the first dean of Theology; the first rector was the accomplished astronomer Martin Pollich von Mellerstadt. Nikolaus Marschalk, a committed humanist who had published in Erfurt the first Greek primers printed in Germany, joined the Faculty of Arts. Among the early professors of law were three trained in the finest Italian schools: Petrus of Ravenna, Johann von Kitzscher, and Christoph Scheurl.

Not all found the transition from established centers of learning easy. In 1505 Christoph Scheurl had made a particularly expansive oration at the University of Bologna, celebrating the German nation’s contribution to letters. The new university at Wittenberg was singled out for special praise.

13

Scheurl extolled the achievement of Frederick the Wise, who he claimed (perhaps unwisely, as he had never been there) had turned his capital from a town of brick into a city of marble. In the event even brick proved slightly optimistic. Three weeks after his arrival Scheurl was longing for the sophisticated Italian companions he had so recently goaded with the perfections of Germany. Wittenbergers, in contrast, he found to be drunken, quarrelsome, and crude.

14

Scheurl was a decent man, and quickly got over this culture shock. Soon he would be guiding his new university as its rector. Students also responded to the new regional institution with enthusiasm. When the university first opened its doors in 1502, 416 students matriculated, with a further 258 the following year.

15

This represented an extraordinary injection of energy into a town of only 2,000 inhabitants. After this, enrollments tailed off, and in 1506 the university faced its first crisis, an eruption of plague that necessitated temporary evacuation to Herzberg. Since this coincided with the foundation of the university of Electoral Brandenburg at Frankfurt-an-der-Oder, there was good reason to believe that students, a notably fickle crowd used to the principle of the

peregrinatio academica,

might desert Wittenberg for good.

It was in this context that Mellerstadt persuaded a colleague, Andreas Meinhardi, to pen a work advertising Wittenberg’s many charms.

16

The dialog introduces us to two students, Reinhard and Meinhard, one headed

to Wittenberg, the other to Cologne. Reinhard is so impressed by what he hears that he decides to revise his plans and join Meinhard in Wittenberg. Their arrival is well-timed, allowing them to visit the castle church on All Saints’ Day and see the relics exhibited. The remaining chapters complete the walking tour with frequent classical allusions in which Wittenberg is compared, rather ambitiously, to Rome. In this respect the dialog demonstrates the danger of treating humanist puff pieces as documentary evidence; but it also shows the energy and commitment that the first generation of pioneers manifested in their new institution.

C

HRISTOPH

S

CHEURL

Scheurl was one of the most talented recruits drawn to the new University of Wittenberg. In an oration in Bologna Scheurl had heaped extravagant praise on the culture of the German north; when he arrived, Wittenberg was something of a culture shock.

Scheurl’s arrival, in 1507, proved something of a turning point. The plague receded, and students could return. New colleagues were

recruited, among them (though at first only as a stand-in for a brief winter semester) Martin Luther. In 1508 Frederick invited Scheurl to draw up new statutes for the university. With characteristic panache Scheurl modeled them on those of the greatest of the Italian universities, Bologna, and a more recent foundation in Germany, Tübingen. Scheurl continued to boost the university in a series of widely circulated orations before moving on, in 1511, to new duties in Nuremberg. The time was ripe for a new generation, supplied by the shrewd patronage of Johann von Staupitz, who in 1511 transferred both Luther and his friend Johann Lang from the Augustinian house in Erfurt. In 1512 the two friends were joined by Georg Spalatin, who took charge of converting the elector’s extensive book collection into a new university library. Spalatin, Frederick’s secretary and confidant, would subsequently play an enormously important role as Luther’s emissary and advocate to the electoral court.

17

In the next years these three friends, Luther, Spalatin, and Lang, would combine to reshape the university around a more aggressive and confrontational intellectual agenda.

FIT FOR PURPOSE

Frederick’s new capital required one other statement of purpose: the provision of a printing press. Thankfully, this needed no great exertion on the elector’s part since the solution lay easily to hand. One of the first teachers of the university, Nikolaus Marschalk, was in possession of a press, and he brought it with him from Erfurt. The first books printed on this press appeared in the year of the university’s foundation, 1502.

18

Despite these promising beginnings, printing in Wittenberg did not flourish. Marschalk operated the press for only two years before he left Wittenberg. The press stayed behind, in the hands of Marschalk’s colleague, Hermann Trebelius. He was, if anything, even less successful, and published only a few titles before he abandoned the venture. Two more printers would come and go before in 1508 the press passed finally into the hands of a man who would stick to the task, Johann Rhau-Grunenberg. For a period from 1506 to 1507, after the departure of Trebelius, Wittenberg seems to have been without a press altogether.

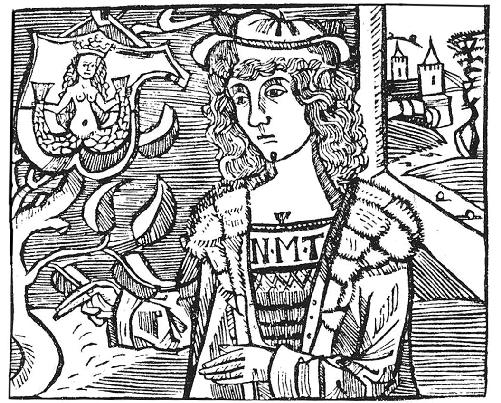

N

IKOLAUS

M

ARSCHALK

A crude woodcut decorating one of Marschalk’s early Erfurt publications. Marschalk was a significant intellectual force in the newly established Wittenberg University; that he operated his own printing press was a further incidental benefit.

The reasons for the repeated failure to create a going concern in Wittenberg are not difficult to discern. Before the foundation of the university in 1502 there had been no printing press in Wittenberg; this was now a full fifty years after printing was first established in Mainz. The new invention had made its way to northeastern Germany, to Erfurt and Leipzig, relatively quickly, but not to Wittenberg.

19

In these intervening fifty years the industry had come a long way. The first generation of pioneers were often closely associated with local universities (as in the case of Paris) or religious houses (Subiaco, near Rome). But by 1500 the industry had passed into the hands of experienced businessmen and artisan craftsmen. In this respect the Wittenberg press, operated by scholar amateurs, was something of a throwback.

The first products of the press sadly bear this out. The concentration of the printing industry into larger, capital-intensive ventures in Europe’s major commercial cities had allowed for considerable investment to refine both the process of production and the aesthetics of the printed page. The larger print shops could marshal a range of typefaces in different styles and sizes. These were used to lead the reader through complex texts, differentiating the text body from notes, signaling section breaks and significant places in the argument.

The products of the early Wittenberg press exhibited none of these characteristics. None of the earliest Wittenberg printers were particularly accomplished, and they had at their disposal only a limited range of types. Marschalk, operating his press as a private concern and essentially as an extension of his scholarly work as a teacher of Greek, possessed some Greek type. This had most likely been obtained through the good offices of Wolfgang Schenk, the Erfurt printer with whom he had worked before coming to Wittenberg. But this veneer of sophistication could not disguise the relative poverty of the range of fonts available to Wittenberg’s first printers.

Nor was there any immediate prospect of the investment necessary to bring any alteration to this situation. In its first fifteen years (if it survived at all) the Wittenberg press was destined to play only a limited role, supplying the local needs of the university’s professors and students. It would print largely the day-to-day necessities of academic life: announcements, a statement of theses to be defended in academic examinations, celebratory orations, and the like.

20

Any more substantial publications, including the standard textbooks required in class, were supplied from elsewhere. It made no sense for Wittenberg’s printers to attempt to compete in this long-established and smoothly functioning market. Nor was there much future in the publication of vernacular literature for local citizens: the size of the town was too small for this sort of speculative commercial publishing.

This all amounted to a fairly obvious recipe for business failure, and this indeed was the fate of Wittenberg’s first printers. A press was only

sustained because Frederick considered it a matter of personal prestige to maintain a local printing house. The most substantial early Wittenberg publications, such as the catalog of the castle relic collection, were almost certainly paid for directly by the elector.

21

But even this substantial volume was unlikely to have kept the press active for more than a few months (the largest expense would have been the woodcuts supplied by Lucas Cranach). No purely commercial printer would have been prepared to make his home in Wittenberg for the promise of such intermittent work. In these circumstances the university authorities might have thought themselves lucky to attract a new printer with at least a rudimentary experience of a working commercial press: Johann Rhau-Grunenberg.