Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town Into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe--And Started the Protestant Reformation (19 page)

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Modern, #General, #Europe, #Western

M

ELCHIOR

L

OTTER

S

ENIOR IN

L

EIPZIG

The superior quality of works published in Leipzig, the established center of printing in the German northeast, was clear for all to see, which is why Luther hoped to lure Lotter to Wittenberg.

The most substantial obstacle in the case of Lotter was that he had a perfectly satisfactory relationship with the old church. It had been Lotter who, in 1516, had published the manual for confessors for the indulgence campaign that had so offended Luther.

41

In 1517 he published

two

editions of Jerome Emser’s life of St. Benno, a great local focus of traditional devotion; in 1518 he would publish the first Catholic attack on Luther, Tetzel’s

Rebuttal,

and two editions of the Roman condemnation of Luther’s teaching on indulgences.

42

Yet a few weeks later he was publishing for Luther.

This was essentially a pragmatic alliance. What seems to have attracted Luther was Lotter’s reputation as a publisher of serious works of Latin scholarship. It was here that Rhau-Grunenberg’s work was most seriously deficient. His plain, undecorated, and utilitarian work reeked of provincialism—precisely the impression Wittenberg could not afford to give now that the university aspired to a leading role in curriculum reform, and Luther’s works found readers in the wider intellectual community. Lotter, in contrast, had years of experience in precisely this sort of work: 475 of the 511 books he had published before 1518 were in Latin.

In the summer of 1518, when Rhau-Grunenberg’s press was hopelessly clogged, Luther was forced to turn to Lotter to get his reply to Prierias into the public domain. At this point Lotter preferred to cover his bases; he published Luther’s text, but in a joint edition with Prierias’s original. That way he could be seen not to have taken sides. On the other hand it could not have escaped his attention that Luther was very good business; this dual edition was printed three times in the first year.

43

While the good Catholic in Lotter might have disapproved, the businessman was definitely interested.

M

ELCHIOR

L

OTTER

J

UNIOR IN

W

ITTENBERG

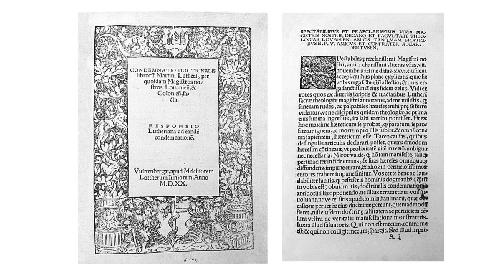

Transposing the technical experience and design quality of a major Leipzig press to Wittenberg was a priority for Luther in 1519. As we can see here, he was not disappointed.

In May 1519 Lotter made a first visit to Luther in Wittenberg. It was clear he was now seriously considering opening a branch office there; shrewdly he wooed Luther by exhibiting a sample of the typefaces he would be employing in any putative Wittenberg books. Luther was enthusiastic: to his well-tutored eye, these typefaces bore comparison with those of Froben, the Basel printer whose edition of Luther’s collected works had made such an impression on him. What a boon it would be, Luther rhapsodized to Spalatin, to have works printed with a Wittenberg imprint with types of this quality. With Lotter’s help Wittenberg would

even be able to contemplate printing in all of the scholarly languages, Greek and Hebrew included.

44

The two men were able to build their working relationship during the Leipzig Disputation, when Luther was lodged in Lotter’s substantial workshop residence.

45

For Luther, used to Rhau-Grunenberg’s much more modest print shop, this busy office must have been a revelation. It was in these weeks, too, that Lotter was engaged in bringing out Luther’s commentary on Galatians, and Luther would have been able to examine its pages as they emerged. This, too, would be a conspicuously successful publication.

46

It was probably during the last days of the Leipzig Disputation, when Karlstadt was again the principal disputant on the Wittenberg side, that the deal with Lotter was sealed.

Lotter was now too well established in Leipzig to move to Wittenberg himself. But he contracted with Luther to establish a branch office in Wittenberg, under the direction of his son. The deal brought with the press a portion of Lotter Senior’s types; others were obtained from Basel, citadel of German humanism and quality printing.

47

The press was up and running by December 1519, having been found space in Lucas Cranach’s capacious factory at Schloβstrasse 1; it was fully operative from the early months of 1520.

The relationship worked well, and indeed, in years to come, as the supply of work dried up in Leipzig, Lotter Senior may have regretted not moving to Wittenberg himself. In all of this Rhau-Grunenberg was not forgotten. Luther would occasionally allow his frustration to boil over, and Rhau-Grunenberg was a convenient scapegoat. But Luther was not one to abandon a loyal friend, and Rhau-Grunenberg continued to receive a fair portion of Luther first editions.

Most of all, Wittenberg was now beginning to assemble the capital and technical infrastructure to deal with the vastly expanding demand for Luther’s works. This was just as well, because the following years would see the interest in Luther, heretic, visionary, or German hero, reach new heights.

5.

O

UTLAW

ARTIN

ARTIN

L

UTHER PUBLISHED

his first work in 1516, a modest introductory essay to the

Theologia Deutsch

of Johannes Tauler. Four years later, at the end of 1520, he was the most prolific living author since the invention of printing seventy years before. This was a primacy that he would retain until the end of the sixteenth century, by which time his works had been published more frequently than any known author in the history of Western letters. This achievement goes beyond the mere statistical. To understand the full extent of Luther’s impact on the book industry, one needs to appreciate how very difficult it had been for living authors to win a hearing at all. The most published authors of the first age of print were almost all historic figures: classical authors such as Cicero or Aristotle, medieval churchmen, and the early church fathers. This stranglehold of the departed was much resented by the new generation of aspiring authors, which is why those who did make the breakthrough, such as Battista Spagnoli and Desiderius Erasmus, were so much admired. But these were both literary men; Luther had somehow made a breakthrough in the most conservative of genres, theology.

Luther owed this extraordinary renown to his own facility as a writer, his versatility, and his willingness to ignore all attempts to silence

him. And it is a profound comment on this phenomenon that this public explosion of interest, incubated in the years 1518 and 1519, reached new heights in 1520 and 1521, the period when Luther was officially pronounced excommunicate and outlaw, officially removed from society and beyond redemption. That such a man should be embraced by a new reading public signaled a profound shift in public consciousness. It also brought into sharp relief the extent of the difficulties the church now faced in bringing him to heel.

GOOD WORKS

In the six months after Leipzig, Luther penned sixteen new works. The year 1520 would pass in a similar blaze of creativity. Friends marveled that he could keep up this relentless program of writing, and certainly it took its toll. But Luther, as he confessed to a friend, never struggled to find words for the task in hand. “I have a fast hand and rapid memory. As I write the thoughts just naturally come to me, so I do not have to force myself or ponder over my materials.”

1

Once he had committed his thoughts to paper, he seldom revised or made corrections. The manuscripts of his work that have survived show little sign of significant second thoughts.

For all that, 1520 did see a perceptible reorientation of his literary activity. The fury of the polemical exchanges that had characterized the months before and after Leipzig for the time receded, and Luther could turn his mind to other tasks. The pastoral and pedagogic writings that had proved so popular continued. And Luther also found space to take stock of the tumultuous change that had been wrought in his faith: his attitude to his church, his perception of his extraordinary place in the unfolding national crisis, the huge reorientation of the theological foundation stones of his belief. From this great work of mental recalibration would emerge the monumental works of theology and ecclesiology for which the year 1520 has been known.

We now associate the Luther of these years with the three great writings in which he set out the new Reformation agenda:

To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation,

The Babylonian Captivity of the Church,

and

The Freedom of a Christian Man

. Contemporaries, it must be said, would not have immediately recognized these as being of a different order from the twenty-five other writings published during the year. Many would have been distracted by the multiple dramas that rumbled through the year, as charge and countercharge followed the fallout from Leipzig, and the pope and Germany’s political powers wrestled over Luther’s fate. In the short term Luther owed his growing public renown as much to his works of pastoral theology, his careful exposition of a healing Gospel, which struck an increasing chord with the German public.

This reorientation after the dramas of Leipzig was one that many of Luther’s friends quietly welcomed. Luther was not at his best in the white heat of controversy. The intensity that he brought to the cut and thrust of academic debate might impress those who witnessed these occasions, but as Leipzig had demonstrated, a wily opponent could lead him in directions where a more politic spirit would not have ventured. Luther was all too inclined to dismiss opponents as ignorant blockheads, where, as Eck had shown, they were anything but; and once driven into dangerous terrain, he would embrace the new radical expression with obstinate defiance. He was not an easy man to follow, as even his most loyal friends were beginning to discover. Particularly in his letters Luther would maintain a running commentary on the polemical exchanges: his mighty efforts to smite his opponents and their feeble replies, their weasel words, poor faith, and cunning, the laughable poverty of their reasoning matched only by their duplicity and witless twisting of his own words. No doubt this was a necessary tension relief at a time when Luther never knew when the next tumult would erupt, or which former friend might speak against him. But for the tight band of his inner circle of confidants these letters often made uncomfortable reading.

So the more subtle among his friends began to lead Luther toward writing tasks that would engage his best qualities. In the summer of 1519

Frederick the Wise had fallen dangerously ill. It was suggested to Luther that the prince would appreciate a comforting meditation, and Luther obliged with a series of beautiful reflections known in Latin as his

Tessaradecas Consolatoria

(

Fourteen Consolations

).

2

Other similar assignments were soon put his way.

Another obvious outlet for Luther’s boundless energy was the spiritual needs of his congregation. One remarkable letter from these years explains why he found it so difficult to make time to translate his explanation of the Lord’s Prayer into Latin. He certainly wanted to do this, he wrote, but he had his lectures and his preaching, his duties to the university, seeing another publication through the press; and in addition “each evening I expound to children and ordinary folk the Commandments and the Lord’s Prayer.”

3

Every evening. At this time he usually also preached three times a week. These relatively mundane pastoral tasks mattered to Luther enormously, and from this experience, enriched by his constantly evolving theological understanding, came some of the richest writings of these years.