Brain Trust (29 page)

Authors: Garth Sundem

So that’s great: five stages of tribal development. But more important than defining these stages is the ability to move up the food chain. How can you design a business with stage four in mind?

If you’re starting from scratch, rather than hiring people at the start-up level who have the longest resumes, “first, find your own values,” says Logan. “Then find people who share these values.” Build around a value statement like Zappo’s “We believe in doing more with less.”

Once you grow past a small pod of naturally like-minded collaborators, “create initiatives that express these core values,” says Logan. In addition to giving new employees a dinner-party answer to the question, What does your company do?, give them

an answer to the question, What does your company believe in? Values give employees something to coalesce around, and this coming together creates a strong tribe.

“If you look at the early Jedi, they became

inept and powerless by denying the Dark Side,” says Logan, now speaking my language. “But at the end of

Return of the Jedi

, what you see is that Luke didn’t defeat evil, but integrated it. As Luke rebuilds the Jedi, will they still be monklike and celibate? No, they’ll balance the Light and Dark Sides.”

To Logan, the same balance is true of good leaders. “My theory is that leaders have a larger dark side than most of us,” he says. “They can tap into its power, but are always at risk of being destroyed by it.” Jimmy Carter is a wonderful person, but was a terrible president, “partly because he never tapped into his dark side,” says Logan. In fact, it’s unclear that Carter even had one.

There’s a huge body of research on individual

intelligence, especially how to measure it, what predicts it, and how to train it. But researchers at Carnegie Mellon just recently provided the first direct evidence for a fixed collective intelligence in groups. Interestingly, factors you might assume made smart groups—including group cohesion, motivation, and satisfaction—had no effect. But there were three things that across many studies created smarter groups: (1) social sensitivity; (2) little variance in members’ number of speaking turns—the conversation wasn’t dominated by one voice; and (3) the proportion of members who were female—though this was due in part to social sensitivity.

I like to believe both that the early bird catches the worm, and that he who mischief hatcheth, mischief catcheth. The root of this desire is surely the fact that I get up early and that for at least the last handful of years I’ve kept my mischief hatching to a minimum—and I like to think that my saintly actions will lead to reward. I also like to believe that if I drive well I will avoid accidents, that if I read to my kids and install the right preschool math applications on my smartphone they will go to Yale, and that if I eat well and exercise I can avoid unhealthy things like dying.

Duke social psychologist Aaron Kay points out that I’m not alone. “In the Western world, people like to believe in a high degree of personal control,” says Kay, “that whatever happens, good or bad, is controlled by your actions.” But sometimes it’s a difficult belief to maintain—sometimes slackers win the lottery while saints are hit by falling pianos. “When we’re reminded of randomness, it creates anxiety,” says Kay, “and when we feel anxious we want to believe that even if we don’t have control, something does.”

By reminding people of this randomness in lab settings, he’s shown that people with diminished personal control are more likely to turn to authoritarian gods or governments. If I wake up early and there are simply no worms, I want to believe that there’s a reason for that lack of worms. God or the government must be to blame—certainly someone must be driving this fun-house ride, right?

Imagine a personal, internal teeter-totter that needs to stay level in order to make everything copacetic with the world (the angle of tilt is your level of anxiety). On one side is control, made up

of personal control, governmental control, and religious control. And on the other side are the events of the world—sometimes a relatively orderly baseline and sometimes a wild jumble of chance.

Now imagine removing some weight from personal control. To keep your metaphysical teeter-totter in balance you need increased government or religious control (or both).

Now imagine plucking a weight from governmental control. Kay showed that in the period of governmental uncertainty before a major election, belief in God goes up (reduced governmental control balanced by increased religious control). Similarly, it seems in the United States as if high religious control is associated with the desire for low governmental control. And, “In countries with little personal or governmental control, you may find more belief channeled into the supernatural option,” says Kay.

However, just as the teeter-totter tipping away from control creates anxiety that people heal by increasing government, religious, or personal control, when the teeter-totter tips toward too much control, people feel oppressed and try to get out from under its thumb. This is an authoritarian government’s revolutionary proletariat or a controlling parent’s teenage daughter.

So the key, as implied by the now overused simile of a teeter-totter, is that of balance. I’m sure you can imagine how to get rid of control in excess of what you need. But if you’re feeling like Earth is tumbling toward the Sun, it can be trickier to take the control you want. Certainly, you can join a controlling church or political party (or even adopt a personal belief in an all-powerful god), but so too can you grab the bull by the horns and increase your personal control of life. Make the present more definite with a daily schedule, making sure to include time that you spend according to your own choosing (see this book’s entry with Sheena Iyengar). And make the future definite with lists, agendas, and long-term life plans.

By taking control of the world around you, you can decrease the anxiety born of a topsy-turvy world.

Aaron Kay and collaborators had Canadian

women read paragraphs about emigration, half of which implied that leaving the country would get easier in the next five years, and half of which implied it would get harder. Then they all read the same paragraph about gender inequality in Canada. How did these two groups view injustice? The group that felt trapped in Canada was less likely to blame inequality on a systemic flaw in their country. It seems that people trapped in a country—by policy or by poverty—are also likely to defend this same system that keeps them trapped.

It’s an old debate: Does perfectionism lead

to increased performance or does it sabotage the perfectionist? Researchers at the Canadian Dalhousie University found compelling evidence of the latter—psychology professors with perfectionist strivings had fewer journal articles, fewer citations, and were published in less prestigious journals than their messy-and-proud peers.

The average Premier League goalkeeper makes about $1.5 million a year. Chelsea keeper Petr Cech makes $145,000 a

week. With cognitive scientist Gabriel Diaz’s help, you can too (or at least you can dominate your adult rec league …). Working in Brett Fajen’s lab at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Diaz covered kickers and the ball itself with enough sensors to make any Hollywood special effects modeler proud. His thought was this: If you can turn the movements that create left shots and right shots into numbers, you can mine these numbers to see which movements best predict right or left ball direction. If you can spot these movements, you can increase the success rate of preemptive dives. And if you can increase the success rate of your preemptive dives, you can yacht the Adriatic Sea and stuff your mattress with dollars (or, see above comment about your adult rec league).

“The point at which the foot contacts the ball is almost 100 percent predictive of left or right,” says Diaz. You’d expect that—where a cue ball hits a colored ball creates the colored ball’s direction. And he confirmed soccer players’ long suspicions that things including plant foot, upper leg direction, hips, and shoulders are moderately predictive.

“But more important,” Diaz continues, “is that we found three sources of distributed information throughout the body that were quite reliable.” A penalty shooter can lie with a plant foot or with shoulders, and so it’s not statistically beneficial to watch any single body part. But keepers would do well to recognize combinations of these body parts—and this remains true even if a kicker points her plant toe left and kicks right. “What this does,” says Diaz, “is bring about changes that cascade through other parts of the body—the distributed information network continues to forecast ball direction.” Perhaps if you deceptively turn your plant foot left, in order to kick the ball right without falling over, some combination of your shoulders, hips, head, and kicking-side hand have to compensate hard right.

To find out if the Force is strong enough with keepers to

recognize these distributed information networks, Diaz played video of the networks in action—they looked like very coordinated marionettes made of the light points that Diaz originally captured with his sensors. In the video, the point-light marionette approaches the ball, swings body and leg, and just as the “foot” hits the “ball” the screen goes blank and subjects have to punch a left or a right button to predict the ball’s direction. Fifteen of thirty-one subjects couldn’t do it. But even in novices, sixteen of the thirty-one were able to beat chance when predicting penalty kick direction based on a kicker’s overall body language during the approach.

So the moral for a trained goalkeeper, especially at a skill level at which kicks are almost assured to go hard into the right- or left-side netting, is to trust the Force. Stretch out with your feelings and trust their evaluation of Diaz’s distributed information networks. The more you trust, the more you’ll beat chance.

In their

Freakonomics

blog at the

New York

Times

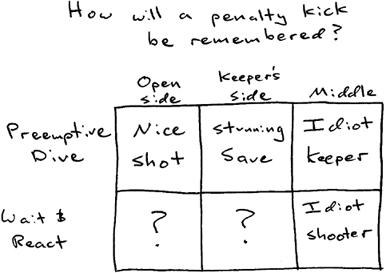

, Stephen Dubner and Steven Levitt point out that penalty kicks are beholden to game theory. Because most goalies guess, the best scoring strategy for a kicker is to blast the ball directly at the goalie’s head—which won’t be there at the point of contact because it’s already in motion trying to stop a ball into the right or left netting. But kickers don’t do this because, “If he misses to the right or left, the moment will be remembered more for the keeper’s competence than for the kicker’s ignominy,” write Dubner and Levitt. Penalty kicks have the game theory payout shown on

this page

.

“Keep your eye on the ball!” Even if you’ve

never played Little League, it’s part of the cultural canon—do you hear it in your mind’s ear when trying to finish a project, or swat a fly, or stay awake during a lecture? Well, Gabriel Diaz points to a study that suggests it may not be the best strategy after all. Michael Land and Peter McLeod tracked the eye movements of cricket batsmen and found that rather than keeping their eyes on the ball, the best batters picked up the ball only at specific points, and then made very quick and very accurate predictions about where to pick it up next. First they watched the release, then accurately ticked their eyes to where they knew the ball would bounce, then watched the bounce and the ball’s trajectory about 100 to 200 ms after, then swung based on their prediction of time and position. The more ahead of the ball were their eyes—leaping from release to the predicted point of bounce—the better the batsman.