Born Survivors (49 page)

Authors: Wendy Holden

After the end of Communist rule in 1989, Anka was finally handed back ownership of the family factory in Třebechovice. ‘I sold it immediately – and very badly – because I didn’t know the first thing about running a factory, and I didn’t want to have anything to do with it somehow.’ She couldn’t help but feel guilty and think what her father would say – ‘First the Germans took it, then the Communists. Now, you sell it of your own free will? How

could

you?’ It was a decision she fretted over for the rest of her life.

Anka never went back to Auschwitz and wanted nothing to do with Germans. Like Rachel, she would have nothing German in the house; she was vehemently against the building of the Channel Tunnel because, she claimed, ‘The Germans could come!’ Years after the war, when new machinery was installed in her husband’s factory, an engineer was sent to show the staff how to use it. Karel invited the engineer, a German, to dinner. Anka served the meal, but when her husband asked where the man came from and he replied, ‘Freiberg, in Saxony,’ she walked out of the room and never spoke another word to him.

Whenever Anka took Eva to London on the train from Cardiff, they had to pass a huge steel works at Newport with tall industrial chimneys that belched smoke and flame. Every time, Anka had to turn her head away. In later life, Anka suffered from an inner ear condition called Ménière’s disease. A specialist told her this was most commonly seen in steelworkers, coalminers and pop stars – people who are subjected to incredibly high levels of noise. He couldn’t imagine where she had developed it until she enlightened him.

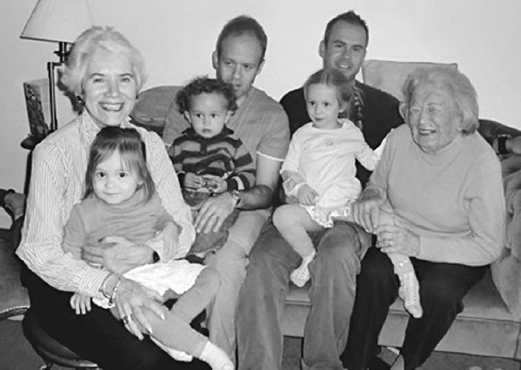

In 1968, aged twenty-three, Eva married Malcolm Clarke, a Gentile who would become a professor of law at Cambridge University. The couple had two sons, Tim and Nick, and three grandchildren – Matilda, Imogen and Theo. Anka knew and loved them all. ‘It was marvellous for my mother,’ said Eva. ‘She couldn’t believe that she had survived or that I had survived and then we had two children and they gave her great-grandchildren. It was a miracle.’

When Anka first met Eva’s father-in-law, Kenneth Clarke, she discovered that he had been an RAF navigator in Bomber Command during the war. He showed her his logbook, which recorded that on 13 February 1945, at 17.40 hours – as she and the rest of the prisoners were locked in the Freiberg factory – he’d flown overhead and helped bomb Dresden in a Lancaster bomber, before returning to his British base at 10.10. He was in tears as he told her, ‘I could have killed you both!’ Anka reassured him with a smile and said, ‘But, Kenneth, you didn’t!’

Anka with Eva, her grandsons Tim and Nick, and great grandchildren Matilda, Imogen and Theo, England

When Eva was living in Singapore with her husband in the late sixties, she wrote and asked her mother to put her story down in writing. She wanted a full written account for her children. Anka agreed. Reading through the account by chance was the first time her husband Karel learned about all that had happened to her during the war, and it moved him deeply.

In later years, Anka went on an emotional journey back to Terezín with Eva as she showed her daughter where she had lived and almost died. When Eva returned alone to the ghetto years afterwards, she was especially touched to find her brother Dan’s name had since been inscribed on a memorial wall there – the only physical trace of the baby whose death had guaranteed Eva’s life.

Anka’s cousin Hana, who had probably only survived the war because she’d married a Gentile, later edited a book of children’s poems and drawings from Terezín called …

I never saw another butterfly …

, quoting the poem by young Pavel Friedman, one of those who’d perished. Hana also became curator of the Jewish Museum in Prague and played a part in arranging for the names of the lost – including those of Bernd and all fifteen members of Anka’s family – to be inscribed on the wall of the Pinkas synagogue.

Having worked behind the scenes in education all her adult life, Eva eventually retired and decided to tell her mother’s story, primarily in schools, travelling all over the country with the Holocaust Educational Trust. Her work inspired a ballet called

Anka’s Story

by a Cambridge dance group, which has been performed at the Edinburgh Fringe. Eva has been to Auschwitz several times with groups of students and teachers and each time she is near the

Sauna

building in Birkenau, her eyes cannot help but scan the ground for her mother’s wedding band and amethyst engagement ring, which were never found.

She took her two sons and Malcolm to Mauthausen for her fortieth birthday in 1985. The former camp is now a beautifully preserved memorial site where visitors from around the world are allowed in at no charge. In 1985, only survivors were allowed in for free and when Eva tried to explain to the man at the gate that she qualified, he laughed in her face and made her cry, refusing to believe her because of her age.

A committed non-believer, Anka’s religious views never changed. ‘Nobody can answer the question – where was He?’ she said. ‘Nobody has solved this, or why we were sought out for this treatment.’ Ever the optimist, she added, ‘If this whole experience had to happen to me, then it was the right age physically and mentally because I was young and strong … As I told my daughter about it at a very early age so I could let go, sort of … I seem to have survived it reasonably well and my child is healthy and her mind is all right, and so for me personally (but only for me, not for my family), it turned out as well as it could have … Eva was my affirmation of life. She took me forward and she helped keep me sane.’

Anka’s husband Karel died of a heart attack in 1983 aged eighty-one.

At his cremation, she saw black smoke coming out of the chimney, shuddered and cried, ‘Why did I have to look?’ His ashes were scattered in the Jewish cemetery near his hometown in the rural Czech Republic. It is not far from an impressive stone memorial, erected to him and to other local people who either left the country to fight the Nazis from abroad or perished in the camps. After Anka had scattered her husband’s ashes, she suggested that Eva cremate her too when the time came, even though that was not in the Jewish tradition. ‘Well, it’s how the rest of my family ended up!’ she joked.

Anka lived with Eva and her husband in Cambridge for the last three years of her life. At ninety-six, she was lucid to the end and always wanted to look her best. Even in her final days, the woman who’d curled her eyelashes en route to see her husband in a ghetto put on make-up to greet her eldest grandson. Immensely proud of her daughter’s work in speaking to students about the Holocaust, she would have been delighted to be remembered in a book. ‘The more people who know about what happened, the less likely it is to happen again, I hope,’ she said. ‘This is a story which should teach people that it

mustn’t

happen again.’

Anka on her 95th birthday with her great-granddaughter Matilda, 2013

Eva agreed. ‘It is very important to remember all those millions of people who were killed. And especially all those who have never had one single person remember them because all of their families and their communities were destroyed. It is our duty to tell that story and to try to prevent such atrocities from happening again and again.’

Anka Nathan-Bergman died at home with Eva by her side on 17 July 2013. In accordance with her wishes, her ashes were scattered at the same site as those of her second husband Karel in the serene Jewish graveyard in the middle of a wood near Drevikov in the Czech Republic.

After sixty-five years in Britain, a country she came to adore but where she had always felt to be an outsider and a refugee, Anka had finally returned to the country she so loved.

Anka’s grave, Czech Republic

The babies reunited with their liberators, the Thunderbolts

‘The Thunderbolts liberated us and the Thunderbolts reunited us,’ Hana Berger Moran insisted from her home in the country of her liberators. She should know. It was Priska’s daughter who, in the summer of 2003, decided to search for the doctors who’d saved her life in Mauthausen fifty-eight years earlier.

‘My mother was still alive and living in Bratislava and I wanted

to find out if Pete was still around too so that we could meet and thank him.’ Searching online, she came across the website of the 11th Armored Division Association of US veterans and discovered that they were about to hold a convention in Illinois. She sent them a letter which appeared on their website and in their quarterly magazine

Thunderbolt

.

After explaining the circumstances of her birth, she wrote:

When the liberation of Mauthausen happened, I was a barely three-week-old baby. As my dear mother loved to say, the tanks had white stars on them and she was absolutely amazed how young all the soldiers were. She remembered the song ‘Roll Out the Barrel’ being played … The surgeons who operated on me did not believe I would survive if I did not get the proper treatment and begged my mother to return with them to the US. She refused to follow their advice, reasoning that she must return home to Bratislava to wait for her husband, my father … I would very much like to find out the names of the surgeons or surgeon and how to contact any person who helped the prisoners following the liberation … I would like to express my deep gratitude to all liberators of the concentration camp Mauthausen.

Hana, who described herself as an ‘underweight little worm’ when she was born, claimed that she was never the heroine of the story. ‘It was my mother who was incredible.’ It took a while, but in early 2005 she received a message from a man who had been nineteen when he was liberated from the Ebensee sub-camp of Mauthausen, and who had since become the US representative of the International Mauthausen Committee. Max Rodrigues Garcia, who lived not far from Hana in San Francisco, had seen her letter and invited her to travel to Mauthausen for the sixtieth anniversary of the liberation, which he hoped that eighty-two-year-old Pete Petersohn might also be able to attend.

In May 2005, Hana and her husband Mark flew to Austria from San Francisco, and Pete and his son Brian flew in from Chicago. At the Hotel Wolfinger in the grand main square of Linz, liberators and their families plus a few survivors were gathering to share stories with men they hadn’t seen in years. Hana was in the crowded dining room when a group in yellow and white Thunderbolt baseball caps walked in, one of whom looked to be older and visibly tired. She had a sudden clear sense that this was Pete. After he’d settled at a corner table she sat down quietly next to him in the middle of an animated conversation, and waited. A sudden silence fell over the room and Max Garcia, sitting near by, was so excited that he had to put a hand over his mouth to stop himself from crying out.