Born Survivors (45 page)

Authors: Wendy Holden

Hana with her son Tommy, daughter-in-law Julie and grandchildren Sasha and Jack

Priska’s chief legacies from the camps were fretting about food and a detestation of the cold. ‘She would always check the refrigerator and the store cupboard and ask, “Do we have enough? Will we run out?”’ said Hana. ‘Fortunately, our home was small so there was only so much she could hoard.’ Priska also loved the luxury of sleep; her bed and its bedding became a focus of her life, especially in her later years.

Towards the end of her life, Priska said, ‘I had a beautiful life with my child after I … gave birth to her in a concentration camp … My daughter is very precious … I thank dear God that he gave me this child and I wish to all mothers that they have the same feeling of love that I have for my daughter. She is a very good mother and a good daughter. She adores her son and she is a good person.’ Ever the optimist, and still thinking only of beautiful things, she added, ‘I survived. We are here. I brought home a baby. That is the most important thing.’

Hana said, ‘My mother was always very driven and very strong. Her favourite word in Slovak was

presadit’

, which means to push forward or to make things happen. I believe that throughout her time in the camps she had a goal to make something happen and that was to survive and to keep me alive.’

Priska suffered from dementia in old age, but she lived long enough to know and love her only grandchild, Tommy. As her condition deteriorated, she repeatedly begged her daughter, ‘Please forgive me,’ but Hana didn’t understand what she was supposed to be forgiving her for. All she knew was that the past had suddenly crowded her mother’s mind again.

Following her ninetieth birthday in August 2006, Priska Löwenbeinová had to be placed in a nursing home. There she was supervised by her own carer, who gave Hana daily bulletins about her mother’s health. Three weeks later Priska was hospitalised for

dehydration and other medical problems. Hana flew to her side from her home in California and was with her for several weeks until she had to fly back to her demanding job. After returning to her nursing home where she mainly slept for two weeks, Priska eventually died peacefully in her sleep on 12 October 2006.

Priska in her eighties in Bratislava

The woman who had lost three babies and her husband Tibor, along with so many members of her immediate family, in the war had devoted the rest of her life to her ‘perfect’ baby, born on a plank in an SS factory during the middle of an air raid. In 1996, ten years before Priska’s death, her baby Hana had donated the tiny smock and bonnet stitched for her by the surviving women of Freiberg to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. Her mother had kept it safe for more than fifty years.

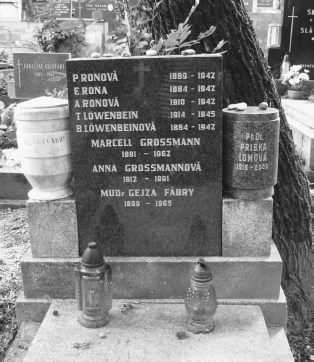

Priska’s ashes are interred in a graveyard in Bratislava which bears the name Slávičie Údolie (Lark Valley). It lies on a tree-lined hill less than a kilometre from the River Danube. She is surrounded by beauty for all eternity.

Family grave where Priska’s ashes are interred, Bratislava

Rachel

In spite of the promises the Abramczyk sisters had made to their father Shaiah to go straight home to Poland after the war, they had to wait for Sala to be well enough to travel, which delayed them until mid-June. ‘When it looked like I was going to make it, we decided to go home as soon as I was strong enough,’ said Sala.

Although they felt pulled back by an invisible thread, the future of the four young women was still deeply uncertain. Only 300,000 of Poland’s 3.3 million Jews had survived the war and an estimated 1,500 were murdered in the years after they returned home, many for anti-semitic reasons. Early hints of such atrocities would have terrified Rachel and her sisters and placed them in an even more unenviable position. Not that they had very much choice. With so many refugees seeking sanctuary abroad, the doors were closed to many alternative destinations. Britain, France and Canada took in thousands but the UK limited the numbers fleeing to Palestine, where many hoped to go. The United States eventually accepted some 400,000 refugees but denied many more access to a new life there. Unwelcome anywhere else in the world, many Polish Jews had little alternative but to return to what was by then a Soviet puppet state.

As the eldest sister at twenty-six, and back in her maternal role, it fell to Rachel to decide what was best not only for her and her baby, but for her three sisters. Sala was twenty-three, Ester twenty, and Bala nineteen when the war ended. What should have been the best six years of their young lives had been spent in ghettos and camps, and they had no life other than what might be left for them in Pabianice or Łódź. The only encouraging news they’d received was from two Polish friends they’d met up with in Mauthausen, who assured them that their father and their brother Berek had been alive the last time they’d seen them two weeks earlier. They had all been in Bergen-Belsen but then separated. If that was true, then they knew that their menfolk would also go to Pabianice as soon as they could and might even be waiting for them already.

Looking ‘not very well-kept’, the four young women clambered into buses and then back into a cattle truck that took them on another interminable journey, one that stopped and started numerous times along the way because of bomb damage, shortage of fuel and broken tracks. Warsaw was unrecognisable to them after the brutal suppression of the uprising, but they didn’t stay long, taking another overcrowded train and eventually a tram to Pabianice.

Back in their hometown, they discovered that everything had changed. Most of the Jews they’d known all their lives had been erased from history. Their parents’ once-beautiful apartment and all their cherished belongings had been stolen. A former employee was living in their flat and refused to relinquish it, claiming that it no longer belonged to them. He said he had been ‘chosen’ by the Communist Party to look after the property on behalf of the authorities.

Friends and neighbours they’d grown up with had helped themselves to whatever they’d wanted too, so the elegant, flower-filled home of their childhood, the one that their mother Fajga referred to as their ‘castle’, was nothing but a memory. There was no trace of her carefully chosen art or her fine china, and the sounds of music and laughter that had permeated their early years echoed only in their memories. All that the sisters were able to salvage were a few precious belongings that their parents had hidden with their most faithful employees, and which were kindly returned to them. Traumatised and homeless, the sisters appealed to the local authority in charge of coordinating the rehoming of returning refugees. They were assigned a small apartment where they waited, still hopeful of being reunited with their father and brother ‘any day’. As the weeks passed and they were forced to sell their few belongings for money on which to exist, their hopes waned. Sala took in sewing to bring in some extra cash, but the little family unit began to realise with a sense of profound shock that they had lost almost everyone and everything from their past.

Of the 12,000 Jews deported from Pabianice during the war, there were only five hundred left. Baby Mark was the only newborn. Every time the sisters went out into the town that long ago had held so many happy memories for them, they were met only with disparaging looks. Not once were they made to feel welcome; Rachel even overheard one woman complaining, ‘They burned them and they burned them, and yet still so many are alive!’

Sala said, ‘Our home was not our home any more. Our whole city didn’t look good to me. It was like a graveyard with no one we knew.’ The pretty blonde who’d always been popular at school could find no familiar faces. Distraught, she hurried to see her former art teacher in order to let her know that she was still alive. ‘My teacher had loved me so much that she’d painted a picture of me. I told my family, “She’ll be so pleased to see me! I’m going to tell her what happened to us.” But she opened the door and said, “You mean you’re still alive?” Then she said, “I don’t have anything for you.” She didn’t even ask what happened. She just shut the door. It was such a slap in the face.’

About a month after they arrived home, the sisters received a letter via an uncle in New York who had contacted the Polish authorities. He’d been informed that their brother Berek was in a hospital in Sweden, having been sent there by the Red Cross to recover from the loss of an eye and other injuries sustained in the camps. Thrilled, the sisters contacted Berek, who sent them a photograph of himself with his head heavily bandaged. ‘He didn’t mention Daddy and we knew then that Daddy didn’t make it,’ said Sala.

There was no mention either of their teenage brother Moniek, who’d so bravely volunteered to help with the smaller children when the Pabianice ghetto was liquidated. They were told about Chełmno. Nor was there any word of their mother Fajga or the perished innocents – siblings Dora and her twin brother Heniek, fourteen, plus the adored ‘baby’ of the family, Maniusia, who would have been twelve. Knowing what they knew by then about

Auschwitz, the sisters had to accept that the laughing voices of their mother, brother and sisters had been silenced for ever. They could only hope that their little family had remained together at the end and hadn’t suffered too much. Sala said, ‘They were young and beautiful and life should have been that way.’

Faced with the loss of their parents and three of their siblings, Bala, to whom Berek had always been closest, suddenly announced that she would travel to Sweden to take care of him. ‘He needs me,’ she said. And – somehow – she made it and took care of him there for many years. It was from Bala that the sisters learned that Berek’s eye had been lost after he was beaten to the ground by a guard when he tried to save their father’s life in Bergen-Belsen. ‘He had managed to protect his father for all that time even though he was too old and weak to do any work, but then Berek was ordered not to help him with some task. He tried to anyway and the guard kicked him in the face and he lost an eye.’ Their father Shaiah was shot dead three days before the camp was liberated.

There was still no word from Monik. Rachel wondered if her husband might be waiting for her in Łódź while he was getting the factory back into shape. With the greatest difficulty, in a country with virtually no transportation system or infrastructure, she travelled there with some male friends for protection only to discover that the factory, too, had been seized. The Jewish population of Łódź, which had numbered more than 200,000 before the war, had dwindled to less than 40,000, most of whom were to move away or emigrate. The family had lost everyone and everything.

‘We knew then that we didn’t want to stay in Poland,’ Sala said. ‘There was nothing for us there.’ In the tumult of post-war Europe, the sisters went to Munich in the American zone, because they were assured that from there they’d be able to relocate to wherever they wanted to go. They arrived in the bomb-ravaged city with only the clothes on their backs and just a suitcase or two of belongings between them. As word spread that survivors from

their district of Poland were settling in Munich, more friends and neighbours drifted there and they soon set up a new community to support each other. Rachel continued to ask anyone who came back if they knew anything of her husband’s whereabouts, half-expecting grim news, but there was no reliable information and he never appeared.

After several months, she came to accept that Monik must have died, although she never found out the exact details or had any idea where his remains were. For a long time she believed that he’d probably been sent to Auschwitz and gassed, but someone from Łódź who knew her brother Berek assured him that Monik had managed to avoid the last transport out of the ghetto and tried to stay in the area. He was eventually shot dead by a ‘German with a revolver’ on the streets of Łódź. However he perished, he never knew that his loyal young wife had survived and given birth to a son. He would forever lie in an imaginary grave on which she could never lay stones, to which she could never take their son.