Bomber Command (56 page)

Tedder showed great interest in the possibilities of pursuing the attack on morale. Portal seemed for a time to favour it. There was intense discussion of a possible four days and nights round-the-clock air assault on Berlin, to precipitate the collapse of the Nazi regime.

The critical point is that none of the Allied leaders resolutely opposed a renewal of area bombing in some form or other, and this was more than enough of a mandate for Sir Arthur Harris. The C-in-C of Bomber Command had never lost faith in the principles

on which he set out to level Germany two and a half years before. He bowed to overwhelming pressure to commit his forces to support

Overlord

, and this they had done wholeheartedly and with great effect. As the German air defences crumbled and losses fell, Harris found himself with more than a thousand first-line aircraft daily available, a surplus of crews so great that by autumn trainees found themselves employed shifting coal, and a range of devices and techniques formidable beyond the dreams of two years before.

Harris was still obliged to seek the authorization of SHAEF headquarters for every operation by his Command, but Tedder himself agreed by August that the army had become far too careless in its demands for strategic-bomber support even in the most unsuitable circumstances, and must be ‘weaned from the drug’. In August, Harris gained SHAEF’s approval for twelve area attacks on German cities, when his forces were not required elsewhere. The biggest raids were those of 16 August, when 809 ‘heavies’ staged a two-pronged attack on Kiel and Stettin.

By early September, the French marshalling-yard campaign was complete, the ‘ski-sites’ had been largely overrun by the armies, and the Chiefs of Staff were addressing themselves to the future of the strategic air offensive. On 14 September a new bombing directive was issued, of which more will be heard later. But by the end of that month, Arnhem had ended, and the mood of the Allies was changing once more.

In the period of strategic hiatus for the airmen in late August and early September, however, they were for a few weeks astonishingly free to pursue their personal inclinations. Spaatz addressed himself to oil. On 11, 12 and 13 September, for example, he launched three great attacks on synthetic plants by 1,136, 888 and 748 aircraft respectively, in which the Luftwaffe once more lost heavily in air battles, its defeat uncompromised by the half-hearted intervention of a few jet fighters. Bomber Command returned, inevitably, to Germany’s cities. On 29 August its aircraft gave terrible proof of their new effectiveness in an attack on Königsberg. A mere 175 Lancasters ‘de-housed’ 134,000 people in a single night. They lost four aircraft.

Harris was going back to the ground that he had so reluctantly abandoned in April. He was able to do so, quite simply, because there was no one among the Allied directors of the war sufficiently determined to stop him.

13 » ‘A QUIET TRIP ALL ROUND’

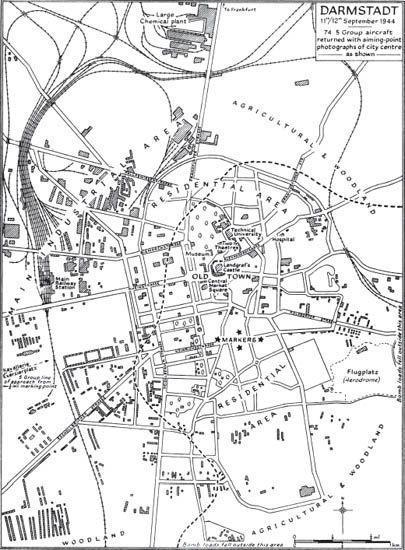

DARMSTADT, 11/12 SEPTEMBER 1944

A quiet trip all round, with everything going according to plan.

83 Squadron debriefing report, 12 September 1944

On the night of 11 September 1944, three days before the Combined Chiefs of Staff issued their directive restoring Bomber Command to Portal’s control and establishing new priorities for the strategic offensive, 5 Group bombed the German town of Darmstadt. 218 Lancasters and 14 Mosquitoes delivered an exceptionally effective attack in which somewhere between eight and twelve thousand people – about a tenth of the town’s population – were killed. In the words of the

United States Strategic Bombing Survey

in 1945:

This was an area raid of the classic saturation type, which had so effectively razed Cologne and Hamburg . . . The mechanics of the raid, between the ‘Target Sighted’ and the ‘Bombs Away’ were almost perfunctory, and as a consequence Darmstadt was virtually destroyed.

From the British point of view, this was not an important operation – it rates only a footnote in the four volumes of the official history. But I propose to describe it in some detail, partly to show the destruction of which Bomber Command was capable by late 1944, but chiefly to give some impression of what it was like to suffer

one of the most devastating forms of assault in the history of war. I have tried to convey the courage and dedication of the aircrew who flew over Germany. In any story of Bomber Command it is also appropriate to show something of the spirit of the enemy below.

Darmstadt was a prosperous provincial town set in rolling farmland studded with woods, some fifteen miles south of Frankfurt. It was primarily a residential and small-business centre, where shopkeepers and craftsmen plied their trades from stores and workshops beside their homes. The heart and pride of Darmstadt was the old town, a maze of narrow, cobbled streets radiating outwards from the seventeenth-century

landgraf

’s castle, whose grey walls and tall bell-tower overlooked the central market square. Among the gabled baroque and renaissance houses stood two theatres, a celebrated museum and a cluster of lesser palaces and great houses built in the days when Hesse was among the most notable independent German principalities. It was ‘typical’ in the manner that made pre-war English tourists nod and exclaim on the charm of the German bourgeoisie. It was a survivor of the greatest age of German culture and architecture.

The old town gave way at its edges to modern houses and widening streets, squares and small parks and a scattering of factories. The south suburb was the smart residential area. Most of the industrial workers lived on the north side, close to the town’s two largest factories, E. Merck and Rohm & Haas, family businesses which between them employed almost half the total workforce of Darmstadt, making chemicals and pharmaceuticals. A number of V-2 rocket technicians were being trained at the Technical University. Almost one in ten of the town’s workers were employed in government offices; the remainder worked in shops, the printing business, or the small factories making photographic paper, leather goods and wood products. Most of the factories were working only a single eight-hour shift a day.

According to the post-war USSBS survey, ‘Darmstadt produced less than two-tenths of 1 per cent of Reich total production, and only an infinitesimal amount of total war production. Consequently, it had a low priority on labour and materials. Nor was the city important as a transportation centre, because it had no port and was by-passed by the principal rail arteries.’ In all, 18.5 per cent of the workforce was employed on production that directly assisted the German war effort.

Being situated in western Germany, Darmstadt had always been readily accessible to Bomber Command, and indeed as early as October 1940 Portal placed it on his list of German cities suggested for proscription. In November 1943, Sir Arthur Harris included it in his great list of towns that he claimed had been damaged by Bomber Command, in his letter to the Prime Minister. But in reality very few bombs had ever hit Darmstadt, whether aimed or not. Over the years, a few crews jettisoned their loads there. There were two ‘nuisance’ raids against the town in the spring of 1944. On one occasion, fifteen USAAF Flying Fortresses attempted a precision attack on the Merck works, without significant effect. On the night of 25 August 1944, 202 5 Group aircraft were dispatched to bomb Darmstadt, but by a series of extraordinary flukes the Master Bomber was compelled to go home with technical failure, both his deputies were shot down en route to the target, and the Illuminating Force dropped their flares well wide. The Main Force arrived to find the VHF wavelength silent, the flare lines already dying. Most aircraft diverted to join the other Bomber Command attack of the night, on Rüsselsheim. Only five crews bombed Darmstadt itself, and a further twenty-five dropped their loads within three miles.

The Darmstadters were not even aware how close they had come to extinction that night. They assumed that the bombs which fell upon them were either jettisoned, or intended as a further nuisance raid, to drive them into the shelters. Before the night of 11 September they had suffered only 181 people killed in air raids. They were vividly aware that this was a trifle by the standards of every great city in Germany, and, to tell the truth, they had become complacent, almost careless about the peril of air attack.

The Allied armies were now scarcely a hundred miles west. To the very end of the war, few Germans sensed the depths of their Führer’s alienation from them, his indifference to their suffering, his deranged determination to drag them with him to Wagnerian cataclysm. But there was little faith left in secret weapons or miraculous deliverance in Darmstadt. Its people had become fatalists, living out their lives in the hope of some ending of the war at tolerable cost in pain and pride.

But they cherished one terrible delusion. After four years of the Allied air offensive, Darmstadters believed that their town had

been deliberately excluded from the Allied target lists. Their great treasure-trove of paintings and works of art had not been evacuated from the city. Night after night they watched the terrible fireworks displays over nearby Mannheim, Frankfurt, Ludwigshaven. They saw the great glow in the sky as other cities burned; the ‘Christmas trees’, as they called them, floating down from the Pathfinder aircraft cascading light; the burning bombers plunging to earth. They felt the earth shaking with the torrent of explosives falling around them. Yet Darmstadt stood, and they often discussed why. Some people said that with the Allied armies already closing on the borders of Germany, the enemy had selected certain cities to be preserved intact for headquarters and billets, and as a sop to the advocates of preserving German culture. Heidelberg, Wiesbaden and Darmstadt were said to be foremost among these. There was another quaint local theory that Darmstadt was marked for salvation because the Prince of Hesse, who was related to the British Royal Family, lived close to the town and still owned extensive property there.

In reality Darmstadt had always been on the British target lists. Like every other town of significant size in Germany, it was included in High Wycombe’s

Guide to the Economic Importance of German Towns and Cities

, subtitled with macabre jocularity ‘The Bomber’s Baedeker’. According to the Guide, Darmstadt included one Grade I target, the Merck factory: ‘It is believed that this works is now concentrating on products of direct war interest at the expense of its production of pharmaceuticals and chemicals,’ declared the May 1944 edition. The Eisenwerk Eberstadt Adolf Riesterer, manufacturing grinding machines and stone saws, was listed as a Grade 3 target. So was the Motorenfabrik Darmstadt AG, ‘who are now reported to be making diesel engines’. Rohm and Haas rated as a Grade 2 target.

Today it is impossible to determine exactly why Darmstadt was selected for attack on 25 August and finally destroyed on 11 September in preference to the scores of other area targets of far greater industrial and military significance. On a given night, a city was chosen from the vast target list generally after verbal discussion, and those who decided the fate of Darmstadt are now dead, or have long forgotten one unmemorable night among six years of war.

1

It is possible, as many historians have sought with Dresden, to seek evidence of a prolonged and rational debate leading to a consciously momentous decision. In reality, in the heat of war and in the midst of a campaign that was waged nightly over a period of years, target choices were made with what might now seem remarkable carelessness. A succession of Air Ministry, Ministry of Economic Warfare and Bomber Command HQ committees had placed a city on the target list, perhaps years before. On a given night a compound of weather, forces available and the state of the German defences determined which was chosen for attack. In September 1944, 5 Group was seeking previously undamaged area targets of manageable size upon which to test the accuracy and effectiveness of various marking and bombing techniques, tolerable cost – in other words at limited penetration inside Germany. Darmstadt met all these criteria perfectly. On the night of 11 September, 5 Group experimented with a new aiming technique. Because Darmstadt had never before been seriously scarred by bombing, it was ideally suited to provide a verdict on the new method and its potential. When

The Times

reported the raid the following morning, the paper stated, according to the Air Ministry public-relations brief: ‘This is a centre of the enemy’s chemical industry.’

Late on the morning of 11 September, the teletypes from 5 Group headquarters at Swinderby began to clatter out the long winding sheet of orders for its bases and squadrons. This was to be an operation exclusively by Cochrane’s men, and thus most of the detailed planning had been done by his own staff rather than High Wycombe.

AC864 SECRET Action Sheet 11 September