Boko Haram (2 page)

Authors: Mike Smith

Prologue: âI Think the Worst Has Happened'

The siege that would shake Nigeria seemed to unfold at shocking speed, young men blowing themselves up in bomb-laden cars, hurling drink cans packed with explosives and gunning down officers with AK-47s, all in the space of a few hours. But for Wellington Asiayei, the horror would play out in slow motion.

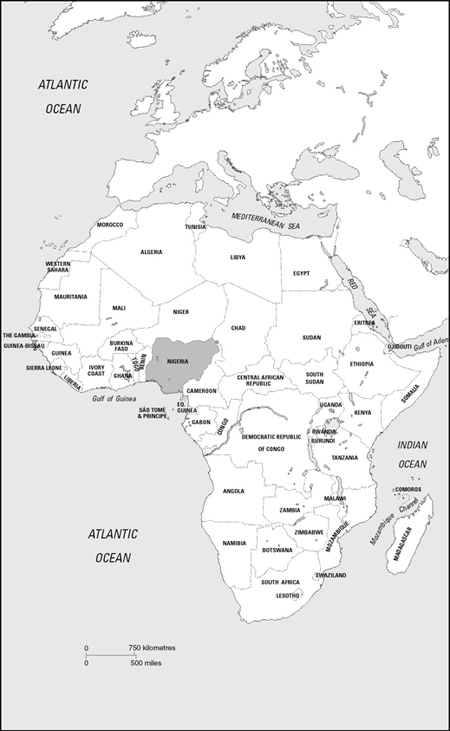

It was a Friday in Kano, the largest city in Nigeria's predominately Muslim north, and prayers at mosques had drawn to an end, worshippers in robes having earlier filed out into streets thick with dust in the midst of a dry season near the Sahara desert. Residents of the crowded and ancient metropolis were returning home, manoeuvring their way through traffic or climbing on to the rear of motorcycle taxis that would zip them through and around lines of cars. At police headquarters in a neighbourhood called Bompai, Wellington Asiayei wrapped up his work for the day and took the short walk back to his room at the barracks to begin preparing his dinner.

When the 48-year-old assistant police superintendent reached his room, he heard explosions. âEverybody from the barracks was running for their dear lives', Asiayei would explain to me three days after the 20 January 2012 attacks. The barracks would soon be empty, but despite the confusion, it would still occur to him to lock the door to his room before fleeing. As he began to do so, he

noticed a young man who looked to be in his twenties and dressed in a police uniform, an AK-47 rifle in his hands. Asiayei knew that members of a certain branch of the force were often assigned to work as guards at the barracks, and he assumed the young man was one of them. He yelled out to him, telling him that they should both run to headquarters. âI saw him raising the rifle at me, and that was all I knew', he said.

noticed a young man who looked to be in his twenties and dressed in a police uniform, an AK-47 rifle in his hands. Asiayei knew that members of a certain branch of the force were often assigned to work as guards at the barracks, and he assumed the young man was one of them. He yelled out to him, telling him that they should both run to headquarters. âI saw him raising the rifle at me, and that was all I knew', he said.

The veteran policeman, still trying to piece together what was happening, felt what seemed to be a gunshot pierce his body. He fell to the ground and lay there face down, blood pooling underneath him. He did not know where the young man with the gun went next. He would remain face down on the floor for what he believed to be hours before a group of women making their way through the barracks spotted him and finally contacted his supervisor, who arranged for a rescue. Asiayei survived, and three days later he and other victims from the same set of attacks would be in a Kano hospital, his bed among lines of others in a sprawling room. The bullet had damaged his spine and lung. He could not walk.

By the time Asiayei was shot, an unprecedented siege of Nigeria's second-largest city was well underway, dozens or perhaps hundreds of young men, a number of them dressed as police officers, swarming neighbourhoods throughout Kano with no remorse for their victims. The first attack occurred at a regional police headquarters, a suicide bomber in a car blowing himself up outside, ripping off much of the roof. The number of explosions then became difficult to count, one after the other, the blasts echoing through the city. Residents said there were more than 20, and judging from the amount of unexploded homemade bombs that police later recovered, that may be a vast understatement. One doctor who helped treat the wounded said the force of some of the blasts caused at least one home to collapse. Witnesses and police said the attackers travelled on motorbikes, in cars and on foot. They included at least five suicide bombers. In one neighbourhood, they threw homemade bombs at a passport office and opened fire. They also attacked a nearby police

station, completely destroying it: the building's tin roof collapsed, the inside burnt, cars outside blackened by fire. Gunshots crackled, corpses were piled on top of one another in the morgue of the city's main hospital and dead bodies were left in the streets to be picked up the next morning. The official toll was 185 people killed, but there was widespread speculation that it was at least 200. It was the deadliest attack yet attributed to the Islamist extremist group that had become known as Boko Haram.

station, completely destroying it: the building's tin roof collapsed, the inside burnt, cars outside blackened by fire. Gunshots crackled, corpses were piled on top of one another in the morgue of the city's main hospital and dead bodies were left in the streets to be picked up the next morning. The official toll was 185 people killed, but there was widespread speculation that it was at least 200. It was the deadliest attack yet attributed to the Islamist extremist group that had become known as Boko Haram.

This was long before the kidnapping of nearly 300 girls from their school in north-eastern Nigeria, an atrocity that would draw the world's attention to an insurgency that had by then left a trail of destruction and carnage so horrifying that some had questioned whether Nigeria was barrelling toward another civil war. To understand what led to the abductions, it is important to first know what occurred in Kano. To begin to wrap one's mind around what happened there â bodies lying in the streets and police helpless to stop a rampaging band of young men engaging in suicide bombings and wholesale slaughter â one must first look backward, not only at the formation of Boko Haram itself, but also at the complex history of Nigeria, Islam in West Africa and the deep corruption that has robbed the continent's biggest oil producer, largest economy and most populous nation of even basic development, keeping the majority of its people agonisingly poor. One must look at colonisation and cultural differences between Nigeria's north and south, the brutality of its security forces and the effects of oil on its economy. But before all of that, it is perhaps best to begin with a charismatic, baby-faced man named Mohammed Yusuf and an episode two and a half years before the attack in Kano.

In a video from 2009, Yusuf can be seen building his argument, the crowd before him off camera but roaring its approval. He describes a confrontation between security forces and his followers when they were on their way to a funeral, and soon he is lashing out at the soldiers and police, accusing them of shooting members

of his sect. It is time to fight back, he says, and to continue fighting until the security task force he believed was set up to track them is withdrawn.

of his sect. It is time to fight back, he says, and to continue fighting until the security task force he believed was set up to track them is withdrawn.

âIt's better for the whole world to be destroyed than to spill the blood of a single Muslim', he says. âThe same way they gunned down our brothers on the way, they will one day come to our gathering and open fire if we allow this to go unchallenged.'

1

1

Yusuf was thought to be 39 at the time and the leader of what had come to be known as Boko Haram. Some had considered him to be a reluctant fighter, content to continue expanding his sect through preaching, but the brutality of the security forces and pressure from his bloodthirsty deputy, Abubakar Shekau, who would later be known as the menacing, bearded man on video threatening to sell kidnapped girls on the market, pushed him toward violence. Not long after the video was recorded, Yusuf would be dead.

His call for his followers to rise up against Nigeria's corrupt government and security forces would lead them to do just that, beginning with attacks on police stations in the country's north. Nigeria's military, not known for its restraint, would soon respond. In July 2009, its armoured vehicles rolled through the streets of the north-eastern city of Maiduguri toward Boko Haram's mosque and headquarters, soldiers opening fire when they drew within range. What resulted was intense fighting that saw soldiers reduce the complex to shards of concrete, twisted metal and burnt cars spread across the site. Around 800 people died over those five days of violence, most of them Boko Haram members. Security forces claimed Yusuf's deputy, Shekau, was among those killed, but they would soon be proved wrong. Yusuf himself somehow survived the brutal assault, but was arrested while hiding in a barn and handed over to police. They shot him dead.

Years later, rubble remains at the former site of the mosque. Shekau has repeatedly shown up on YouTube or videos distributed to journalists to denounce the West and Nigeria's government and Boko Haram, once a Salafist sect based in Nigeria's north-east, has

morphed into something far more deadly and ruthless: a hydra-headed monster further complicated by imitators and criminal gangs who commit violence under the guise of the group. Throughout years of renewed violence, it had been building toward a headline-grabbing assault that would shock the world, and it would do just that in April 2014 with the kidnappings of nearly 300 girls from a school in Chibok, deep in Nigeria's remote north-east. The abductions and response to them would lay bare for the world to see the viciousness of Boko Haram as well as the dysfunction of Nigeria's government and military. But for Nigerians, it was yet another atrocity in a long list of them.

morphed into something far more deadly and ruthless: a hydra-headed monster further complicated by imitators and criminal gangs who commit violence under the guise of the group. Throughout years of renewed violence, it had been building toward a headline-grabbing assault that would shock the world, and it would do just that in April 2014 with the kidnappings of nearly 300 girls from a school in Chibok, deep in Nigeria's remote north-east. The abductions and response to them would lay bare for the world to see the viciousness of Boko Haram as well as the dysfunction of Nigeria's government and military. But for Nigerians, it was yet another atrocity in a long list of them.

Boko Haram had been dormant for more than a year after the 2009 military assault which killed Yusuf, with Shekau, believed to have been shot in the leg, said to have fled, possibly for Chad and Sudan. During that time, authorities in Maiduguri remained deeply suspicious and on the alert for any new uprising. Academics and others in the area with knowledge of the situation predicted a return to violence, saying underlying issues of deep poverty, corruption, a lack of proper education and few jobs left young people with very little hope for the future. Journalists, including myself, visiting Maiduguri one year after the 2009 uprising were made to understand they were not welcome, with secret police trailing our movements. The police commissioner for Borno state, of which Maiduguri is the capital, refused outright to discuss Boko Haram at the time and warned journalists they could be arrested for even uttering those words. Despite such restrictions, I and two other journalists were able to carry out a number of interviews, including with one man who claimed to be a Boko Haram member â a claim to be taken with a heavy dose of scepticism. Looking back now, I have serious doubts about whether he was indeed a Boko Haram follower, particularly since intelligence agents were monitoring us and would have likely questioned him if they suspected him of being one, but certain details of what he told us seemed to ring true in retrospect, whether by coincidence or otherwise.

Through a local contact, we arranged for the man to be brought to our hotel, a hulking building out of sync with its scrubby savannah surroundings. There were few other guests, and the hotel, the Maiduguri International, was badly in disrepair, with mouldy carpets and dirty sheets. Staff, including employees who said they had not been paid in months, refused to turn on the generator for much of the day, leaving the hotel without electricity, since Nigeria was, and remains, unable to produce anywhere near enough power for its burgeoning population. It felt as if we had taken up residence in an abandoned building.

The supposed Boko Haram member, dressed in the same type of caftan any average Maiduguri resident would wear, was led into one of our rooms and took a seat in a chair. I pulled up across from him and began asking him questions, a Nigerian correspondent who works for my news agency translating. The man, who spoke in Hausa, said he was 35 years old, and he claimed Boko Haram members had weapons hidden in various parts of the country with a plan of eventually striking again. Despite my repeated attempts to lead him into explaining in detail why one would willingly join such a violent group, he mostly spoke in generalities.

âWe are ordained by Allah to be prepared and amass weapons in case the enemy attacks', he said. âAnybody who doesn't like Islam, works against the establishment of an Islamic state, who is against the Prophet, is an enemy.'

At the time, we, like so many others, could see the elements that could spark another uprising, the deeply rooted problems that had led to such hopelessness, and we certainly felt that more violence was possible, if not likely. We would not have to wait long for a more definitive answer. Any sense of normalcy the police commissioner and others hoped to portray would soon be shattered. Boko Haram's deadliest and most symbolic attacks were yet to come.

* â

â

* â

â

*

In some ways, unrest seems inevitable in parts of northern Nigeria, a country thrown together by colonialists who combined vastly different cultures, traditions and ethnicities under one nation. This was the case for many African civilisations, but a number of factors would make Nigeria a particularly volatile example, and one must of course start with the oil.

Nigeria first struck oil in commercial quantities in 1956 among the vast and labyrinthine swamps of the Niger Delta in the country's south. Commercial production began in relatively small amounts at first, but new discoveries would soon come, offshore drilling would eventually take hold and Nigeria would become the biggest oil producer in Africa, gaining astounding amounts of money for its coffers â and a list of profound, even catastrophic, problems to go with it. So much of that money would be stolen and tragically misspent, leading to the entrenchment of what has been called a kleptocracy, assured of its vast oil reserves but with electricity blackouts multiple times per day and poorly paid policemen collecting bribes from drivers at roadblocks, to name two examples among many. Most telling is the fact that it must import most of its fuel despite its oil, with the country unable to build enough refineries or keep the ones it has functioning at capacity to process its crude oil on its own. On top of that, petrol imports are subsidised by the government through a system that has been alleged to be outrageously mismanaged and corrupt. In other words, Nigeria essentially buys back refined oil after selling it in crude form â and at an inflated cost thanks to the middlemen gaming the system.

All the while, Nigeria's population has been rapidly expanding. It is currently the most populous country in Africa with some 170 million people, including an exploding and restless youth population. It also recently overtook South Africa as the continent's biggest economy strictly in terms of GDP size, but its population is far larger, meaning the average Nigerian remains much poorer than the average South African. The title of Africa's biggest economy

means little or nothing to most Nigerians, the majority of whom continue to live on less than $1 per day.

means little or nothing to most Nigerians, the majority of whom continue to live on less than $1 per day.

It is those Nigerians who are obliged to scrape whatever living they can in whichever way they can find it, while their leaders and corrupt business moguls force their way between traffic in SUVs with police escorts and seal themselves off inside walled complexes. The daily struggle to survive has led to all sorts of outlandish schemes that have, much to the chagrin of hard-working Nigerians, badly damaged the country's reputation. Emails from Nigerian âprinces' promising riches have become so common worldwide that they are now a punchline, but that is only one part of the problem. In Nigeria itself, many residents have taken to painting the words âBeware 419: this house is not for sale' on the outside walls of houses in a bid to keep imposters claiming to be the owners from selling them when no one is there. The number 419 refers to a section of the criminal code, and all such forms of financial trickery have come to be known as 419 scams. Another infamous example involves the police. Newcomers learn quickly that being pulled over by a policeman can be a maddening experience. They have been known to jump into the passenger seat and refuse to exit until they are âdashed', or bribed, even if the driver has done nothing wrong. The almighty dash is central to Nigerian life.

Other books

They Spread Their Wings by Alastair Goodrum

The Shortstop by A. M. Madden

What Laurel Sees: a love story (A Redeeming Romance Mystery) by Susan Rohrer

The Nurse's Newborn Gift by Wendy S. Marcus

What Killed Jane Austen?: And Other Medical Mysteries by George Biro and Jim Leavesley

Be My Prince by Julianne MacLean

The Interstellar Age by Jim Bell

Murder is a Girl's Best Friend by Matetsky, Amanda

Runaway Miss by Mary Nichols