Blue Highways (6 page)

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

I told him. I’d been gone only six days, but my account of the trip already had taken on some polish.

He nodded. “Satisfaction is doin’ what’s important to yourself. A man ought to honor other people, but he’s got to honor what he believes in too.”

As I started the engine, Wheeler said, “If you get back this way, stop in and see me. Always got beans and taters and a little piece of meat.”

Down along the ridge, I wondered why it’s always those who live on little who are the ones to ask you to dinner.

N

AMELESS

, Tennessee, was a town of maybe ninety people if you pushed it, a dozen houses along the road, a couple of barns, same number of churches, a general merchandise store selling Fire Chief gasoline, and a community center with a lighted volleyball court. Behind the center was an open-roof, rusting metal privy with

PAINT ME

on the door; in the hollow of a nearby oak lay a full pint of Jack Daniel’s Black Label. From the houses, the odor of coal smoke.

Next to a red tobacco barn stood the general merchandise with a poster of Senator Albert Gore, Jr., smiling from the window. I knocked. The door opened partway. A tall, thin man said, “Closed up. For good,” and started to shut the door.

“Don’t want to buy anything. Just a question for Mr. Thurmond Watts.”

The man peered through the slight opening. He looked me over. “What question would that be?”

“If this is Nameless, Tennessee, could he tell me how it got that name?”

The man turned back into the store and called out, “Miss Ginny! Somebody here wants to know how Nameless come to be Nameless.”

Miss Ginny edged to the door and looked me and my truck over. Clearly, she didn’t approve. She said, “You know as well as I do, Thurmond. Don’t keep him on the stoop in the damp to tell him.” Miss Ginny, I found out, was Mrs. Virginia Watts, Thurmond’s wife.

I stepped in and they both began telling the story, adding a detail here, the other correcting a fact there, both smiling at the foolishness of it all. It seems the hilltop settlement went for years without a name. Then one day the Post Office Department told the people if they wanted mail up on the mountain they would have to give the place a name you could properly address a letter to. The community met; there were only a handful, but they commenced debating. Some wanted patriotic names, some names from nature, one man recommended in all seriousness his own name. They couldn’t agree, and they ran out of names to argue about. Finally, a fellow tired of the talk; he didn’t like the mail he received anyway. “Forget the durn Post Office,” he said. “This here’s a nameless place if I ever seen one, so leave it be.” And that’s just what they did.

Watts pointed out the window. “We used to have signs on the road, but the Halloween boys keep tearin’ them down.”

“You think Nameless is a funny name,” Miss Ginny said. “I see it plain in your eyes. Well, you take yourself up north a piece to Difficult or Defeated or Shake Rag. Now them are silly names.”

The old store, lighted only by three fifty-watt bulbs, smelled of coal oil and baking bread. In the middle of the rectangular room, where the oak floor sagged a little, stood an iron stove. To the right was a wooden table with an unfinished game of checkers and a stool made from an apple-tree stump. On shelves around the walls sat earthen jugs with corncob stoppers, a few canned goods, and some of the two thousand old clocks and clockworks Thurmond Watts owned. Only one was ticking; the others he just looked at. I asked how long he’d been in the store.

“Thirty-five years, but we closed the first day of the year. We’re hopin’ to sell it to a churchly couple. Upright people. No athians.”

“Did you build this store?”

“I built this one, but it’s the third general store on the ground. I fear it’ll be the last. I take no pleasure in that. Once you could come in here for a gallon of paint, a pickle, a pair of shoes, and a can of corn.”

“Or horehound candy,” Miss Ginny said. “Or corsets and salves. We had cough syrups and all that for the body. In season, we’d buy and sell blackberries and walnuts and chestnuts, before the blight got them. And outside, Thurmond milled corn and sharpened plows. Even shoed a horse sometimes.”

“We could fix up a horse or a man or a baby,” Watts said.

“Thurmond, tell him we had a doctor on the ridge in them days.”

“We had a doctor on the ridge in them days. As good as any doctor alivin’. He’d cut a crooked toenail or deliver a woman. Dead these last years.”

“I got some bad ham meat one day,” Miss Ginny said, “and took to vomitin’. All day, all night. Hangin’ on the drop edge of yonder. I said to Thurmond, ‘Thurmond, unless you want shut of me, call the doctor.’”

“I studied on it,” Watts said.

“You never did. You got him right now. He come over and put three drops of iodeen in half a glass of well water. I drank it down and the vomitin’ stopped with the last swallow. Would you think iodeen could do that?”

“He put Miss Ginny on one teaspoon of spirits of ammonia in well water for her nerves. Ain’t nothin’ works better for her to this day.”

“Calms me like the hand of the Lord.”

Hilda, the Wattses’ daughter, came out of the backroom. “I remember him,” she said. “I was just a baby. Y’all were talkin’ to him, and he lifted me up on the counter and gave me a stick of Juicy Fruit and a piece of cheese.”

“Knew the old medicines,” Watts said. “Only drugstore he needed was a good kitchen cabinet. None of them antee-beeotics that hit you worsen your ailment. Forgotten lore now, the old medicines, because they ain’t profit in iodeen.”

Miss Ginny started back to the side room where she and her sister Marilyn were taking apart a duck-down mattress to make bolsters. She stopped at the window for another look at Ghost Dancing. “How do you sleep in that thing? Ain’t you all cramped and cold?”

“How does the clam sleep in his shell?” Watts said in my defense.

“Thurmond, get the boy a piece of buttermilk pie afore he goes on.”

“Hilda, get him some buttermilk pie.” He looked at me. “You like good music?” I said I did. He cranked up an old Edison phonograph, the kind with the big morning-glory blossom for a speaker, and put on a wax cylinder. “This will be ‘My Mother’s Prayer,’” he said.

While I ate buttermilk pie, Watts served as disc jockey of Nameless, Tennessee. “Here’s ‘Mountain Rose.’” It was one of those moments that you know at the time will stay with you to the grave: the sweet pie, the gaunt man playing the old music, the coals in the stove glowing orange, the scent of kerosene and hot bread. “Here’s ‘Evening Rhapsody.’” The music was so heavily romantic we both laughed. I thought: It is for this I have come.

Feathered over and giggling, Miss Ginny stepped from the side room. She knew she was a sight. “Thurmond, give him some lunch. Still looks hungry.”

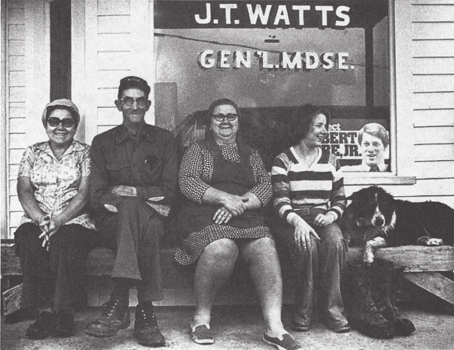

4. The Wattses: Marilyn, Thurmond, Virginia, and Hilda in Nameless, Tennessee

Hilda pulled food off the woodstove in the backroom: home-butchered and canned whole-hog sausage, home-canned June apples, turnip greens, cole slaw, potatoes, stuffing, hot cornbread. All delicious.

Watts and Hilda sat and talked while I ate. “Wish you would join me.”

“We’ve ate,” Watts said. “Cain’t beat a woodstove for flavorful cookin’.”

He told me he was raised in a one-hundred-fifty-year-old cabin still standing in one of the hollows. “How many’s left,” he said, “that grew up in a log cabin? I ain’t the last surely, but I must be climbin’ on the list.”

Hilda cleared the table. “You Watts ladies know how to cook.”

“She’s in nursin’ school at Tennessee Tech. I went over for one of them football games last year there at Coevul.” To say

Cookeville,

you let the word collapse in upon itself so that it comes out “Coevul.”

“Do you like football?” I asked.

“Don’t know. I was so high up in that stadium, I never opened my eyes.”

Watts went to the back and returned with a fat spiral notebook that he set on the table. His expression had changed. “Miss Ginny’s

Deathbook

.”

The thing startled me. Was it something I was supposed to sign? He opened it but said nothing. There were scads of names written in a tidy hand over pages incised to crinkliness by a ballpoint. Chronologically, the names had piled up: wives, grandparents, a stillborn infant, relatives, friends close and distant. Names, names. After each, the date of

the

unknown finally known and transcribed. The last entry bore yesterday’s date.

“She’s wrote out twenty years’ worth. Ever day she listens to the hospital report on the radio and puts the names in. Folks come by to check a date. Or they just turn through the books. Read them like a scrapbook.”

Hilda said, “Like Saint Peter at the gates inscribin’ the names.”

Watts took my arm. “Come along.” He led me to the fruit cellar under the store. As we went down, he said, “Always take a newborn baby upstairs afore you take him downstairs, otherwise you’ll incline him downwards.”

The cellar was dry and full of cobwebs and jar after jar of home-canned food, the bottles organized as a shopkeeper would: sausage, pumpkin, sweet pickles, tomatoes, corn relish, blackberries, peppers, squash, jellies. He held a hand out toward the dusty bottles. “Our tomorrows.”

Upstairs again, he said, “Hope to sell the store to the right folk. I see now, though, it’ll be somebody offen the ridge. I’ve studied on it, and maybe it’s the end of our place.” He stirred the coals. “This store could give a comfortable livin’, but not likely get you rich. But just gettin’ by is dice rollin’ to people nowadays. I never did see my day guaranteed.”

When it was time to go, Watts said, “If you find anyone along your way wants a good store—on the road to Cordell Hull Lake—tell them about us.”

I said I would. Miss Ginny and Hilda and Marilyn came out to say goodbye. It was cold and drizzling again. “Weather to give a man the weary dismals,” Watts grumbled. “Where you headed from here?”

“I don’t know.”

“Cain’t get lost then.”

Miss Ginny looked again at my rig. It had worried her from the first as it had my mother. “I hope you don’t get yourself kilt in that durn thing gallivantin’ around the country.”

“Come back when the hills dry off,” Watts said. “We’ll go lookin’ for some of them round rocks all sparkly inside.”

I thought a moment. “Geodes?”

“Them’s the ones. The county’s properly full of them.”

C

OOKEVILLE

: Easter morning and cold as the bottom of Dante’s Hell. Winter had returned from somewhere, whistling thin, bluish snowflakes along the ground, bowing the jonquils. I couldn’t warm up. The night had been full of dreams moving through my sleep like schools of ocean fish that dart this way, turn suddenly another way, never resting. I hung in the old depths, the currents bending and enfolding me as the sea does fronds of eelgrass.

Route 62 went across the Cumberland Plateau strip-mining country and up into the mountains again. In the absence of billboards were small, ineptly lettered signs:

USED FURNITURE, HOT SANDWITCHES, TURKEY SHOOT SATERDAY (NO DRINKING ALOUD).

It was like reading over someone’s shoulder.

Wartburg, on the edge of the dark Cumberlands, dripped in a cold mist blowing down off the knobs. Cafes closed, I had no choice but to go back into the wet mountain gloom. Under massive walls of black shale hanging above the road like threats, the highway turned ugly past Frozen Head State Park; at each trash dumpster pullout, soggy sofas or chairs lay encircled by dismal, acrid smoke from smoldering junk. Golden Styrofoam from Big Mac containers blew about as if Zeus had just raped Danae. Shoot the Hamburglar on sight.

The mountains opened, and Oak Ridge, a town the federal government hid away in the southern Appalachians during the Second World War for the purpose of carving a future out of pitchblende, lay below. Here, scientists working on the Manhattan Project had made plutonium. In the bookstore of the Museum of Atomic Energy were

The Complete Book of Heating With Wood

and

Build Your Own Low-Cost Log Home

.

Again to the mountains and more spinning the steering wheel back and forth, more first gear, more mist that made everything wet and washed nothing clean. Narrow, shoulderless highway 61 looked as if a tar pot had overturned at the summit and trickled a crooked course down. A genuine white-knuckle road.

I should have stopped at Tazewell before the light went entirely, but no. It was as if the mountains had me. Across the Clinch River and into the Clinch Mountains; a

YOUR HIGHWAY TAXES AT WORK

sign loomed up and then one in heart-sinking, detour orange:

CONSTRUCTION AHEAD.

It should have said,

ABANDON ALL HOPE YE WHO ENTER HERE

. Figuring I was past the point of return, I pressed on. The pavement ended and the road became a crater-shot slough of gravel-impacted mud that shook the Ghost so terribly at ten miles an hour my foot repeatedly slipped off the accelerator. Other crossers, trying to find the roadbed, veered toward each other only to peel apart at the last minute in a blinding spray of red grit. Jaws tight, hands locked to wheel. Clench Mountain. Higher up, headlights pointed at me although we both were crossing west to east. At each bent-back curve, my lights shone off into clouds, which turned the route into a hellacious celestial highway. It was as if I’d died—one of those movies where somebody breathes his last but still thinks he’s alive.