Blue Highways (2 page)

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

In the approaching car beams, raindrops spattering the road became little beacons. I bent over the wheel to steer along the divider stripes. A frog, long-leggedy and green, belly-flopped across the road to the side where the puddles would be better. The land, still cold and wintery, was alive with creatures that trusted in the coming of spring.

On through Lebanon, a brick-street village where Charles Dickens spent a night in the Mermaid Inn; on down the Illinois roads—roads that leave you ill and annoyed, the joke went—all the way dodging chuckholes that

Time

magazine said Americans would spend 626 million dollars in extra fuel swerving around. Then onto I-64, a new interstate that cuts across southern Illinois and Indiana without going through a single town. If a world lay out there, it was far from me. On and on. Behind, only a red wash of taillights.

At Grayville, Illinois, on the Wabash River, I pulled up for the night on North Street and parked in front of the old picture show. The marquee said

TRAVELOGUE TODAY

, or it would have if the

O

’s had been there. I should have gone to a cafe and struck up a conversation; instead I stumbled to the bunk in the back of my rig, undressed, zipped into the sleeping bag, and watched things go dark. I fought desolation and wrestled memories of the Indian wars.

First night on the road. I’ve read that fawns have no scent so that predators cannot track them down. For me, I heard the past snuffling about somewhere close.

T

HE

rain came again in the night and moved on east to leave a morning of cool overcast. In Well’s Restaurant I said to a man whose cap told me what fertilizer he used, “You’ve got a clean little town here.”

“Grayville’s bigger than a whale, but the oil riggers get us a mite dirty around the ears,” he said. “I’ve got no oil myself, not that I haven’t drilled up a sieve.” He jerked his thumb heavenward. “Gave me beans, but if I’da got my rightful druthers, I’da took oil.” He adjusted his cap. “So what’s your line?”

“Don’t have one.”

“How’s that work?”

“It doesn’t and isn’t.”

He grunted and went back to his coffee. The man took me for a bindlestiff. Next time I’d say I sold ventilated aluminum awnings or repaired long-rinse cycles on Whirlpools. Now my presence disturbed him. After the third tilt of his empty cup, he tried to make sense of me by asking where I was from and why I was so far from home. I hadn’t traveled even three hundred miles yet. I told him I planned to drive around the country on the smallest roads I could find.

“Goddamn,” he said, “if screwball things don’t happen every day even in this town. The country’s all alike now.” On that second day of the new season, I guess I was his screwball thing.

Along the road: old snow hidden from the sun lay in sooty heaps, but the interstate ran clear of cinders and salt deposits, the culverts gushed with splash and slosh, and the streams, covering the low cornfields, filled the old soil with richness gathered in their meanderings.

Ghost Dancing

Driving through the washed land in my small self-propelled box—a “wheel estate,” a mechanic had called it—I felt clean and almost disentangled. I had what I needed for now, much of it stowed under the wooden bunk:

1 sleeping bag and blanket;

1 Coleman cooler (empty but for a can of chopped liver a friend had given me so there would

always

be something to eat);

1 Rubbermaid basin and a plastic gallon jug (the sink);

1 Sears, Roebuck portable toilet;

1 Optimus 8R white gas cook stove (hardly bigger than a can of beans);

1 knapsack of utensils, a pot, a skillet;

1 U.S. Navy seabag of clothes;

1 tool kit;

1 satchel of notebooks, pens, road atlas, and a microcassette recorder;

2 Nikon F2 35mm cameras and five lenses;

2 vade mecums: Whitman’s

Leaves of Grass

and Neihardt’s

Black Elk Speaks

.

In my billfold were four gasoline credit cards and twenty-six dollars. Hidden under the dash were the remnants of my savings account: $428.

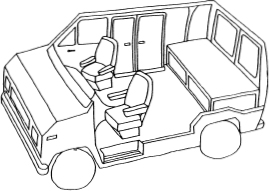

Ghost Dancing, a 1975 half-ton Econoline (the smallest van Ford then made), rode self-contained but not self-containing. So I hoped. It had two worn rear tires and an ominous knocking in the waterpump. I had converted the van from a clangy tin box into a place at once a six-by-ten bedroom, kitchen, bathroom, parlor. Everything simple and lightweight—no crushed velvet upholstery, no wine racks, no built-in television. It came equipped with power nothing and drove like what it was: a truck. Your basic plumber’s model.

The Wabash divides southern Illinois from Indiana. East of the fluvial flood plain, a sense of the unknown, the addiction of the traveler, began seeping in. Abruptly, Pokeberry Creek came and went before I could see it. The interstate afforded easy passage over the Hoosierland, so easy it gave no sense of the up and down of the country; worse, it hid away the people. Life doesn’t happen along interstates. It’s against the law.

At the Huntingburg exit, I turned off and headed for the Ohio River. Indiana 66, a road so crooked it could run for the legislature, took me into the hilly fields of

CHEW MAIL POUCH

barns, past Christ-of-the-Ohio Catholic Church, through the Swiss town of Tell City with its statue of William and his crossbow and nervous son. On past the old stone riverfront houses in Cannelton, on up along the Ohio, the muddy banks sometimes not ten feet from the road. The brown water rolled and roiled. Under wooded bluffs I stopped to stretch among the periwinkle. At the edge of a field, Sulphur Spring bubbled up beneath a cover of dead leaves. Shawnees once believed in the curative power of the water, and settlers even bottled it. I cleared the small spring for a taste. Bad enough to cure something.

I crossed into the Eastern Time Zone and then over the Blue River, which was a brown creek. Blue, Green, Red: yes—yet who ever heard of a Brown River? For some reason, the farther west the river and the scarcer the water, the more honest the names become: Stinking Water Branch, Dead Horse Fork, Cutthroat Gulch, Damnation Creek. Perhaps the old trailmen and prospectors figured settlers would be slower to build along a river named Calamity.

On through what was left of White Cloud, through the old statehouse town of Corydon, I drove to get the miles between me and home. Daniel Boone moved on at the sight of smoke from a new neighbor’s chimney; I was moving from the sight of my own. Although the past may not repeat itself, it does rhyme, Mark Twain said. As soon as my worries became only the old immediate worries of the road—When’s the rain going to stop? Who can you trust to fix a waterpump around here? Where’s the best pie in town?—then I would slow down.

I took the nearest Ohio River bridge at Louisville and whipped around the city and went into Pewee Valley and on to La Grange, where seven daily Louisville & Nashville freight trains ran right down Main Street. Then southeast.

Curling, dropping, trying to follow a stream, Kentucky 53 looked as if it needed someone to take the slack out of it. On that gray late afternoon, the creek ran full and clear under the rock ledges that dripped out the last meltwater. In spite of snow packs here and about, a woman bent to the planting of a switch of a tree, one man tilled mulch into his garden, another cleaned a birdhouse.

At Shelbyville I stopped for supper and the night. Just outside of town and surrounded by cattle and pastures was Claudia Sanders Dinner House, a low building attached to an old brick farmhouse with a red roof. I didn’t make the connection in names until I was inside and saw a mantel full of coffee mugs of a smiling Colonel Harland Sanders. Claudia was his wife, and the Colonel once worked out of the farmhouse before the great buckets-in-the-sky poured down their golden bounty of extra crispy. The Dinner House specialized in Kentucky ham and country-style vegetables.

I waited for a table. A man, in a suit of sharp creases, and his wife, her jacket lying as straight as an accountant’s left margin, suggested I join them. “You can’t be as dismal as you look,” she said. “Just hunger, we decided.”

“Hunger’s the word,” I said.

We talked and I sat waiting for the question. It got there before the olives and celery. “What do you do?” the husband asked.

I told my lie, turned it to a joke, and then gave an answer too long. As I talked, the man put a pair of forks, a spoon, and knife into a lever system that changed directions twice before lifting his salad plate.

He said, “I notice that you use

work

and

job

interchangeably. Oughten to do that. A job’s what you force yourself to pay attention to for money. With work, you don’t have to force yourself. There are a lot of jobs in this country, and that’s good because they keep people occupied. That’s why they’re called ‘occupations.’”

The woman said, “Cal works at General Electric in Louisville. He’s a metallurgical engineer.”

“I don’t

work

there, I’m employed there,” he said to her. Then to me, “I’m supposed to spend my time ‘imagineering,’ but the job isn’t so much a matter of getting something new made. It’s a matter of making it

look like

we’re getting something made. You know what my work is? You know what I pay attention to? Covering my tracks. Pretending, covering my tracks, and getting through another day. That’s my work. Imagineering’s my job.”

“It isn’t that bad, darling.”

“It isn’t that bad on a stick. What I do doesn’t matter. There’s no damn future whatsoever in what I do, and I don’t mean built-in obsolescence. What I do begins and stops each day. There’s no convergence between what I know and what I do. And even less with what I

want

to know.”

Now he was hoisting his wife’s salad plate, rolling her cherry tomato around. “You’ve learned lots,” she said. “Just lots.”

“I’ve learned this, Twinkie: when America outgrows engineering, we’ll begin to have something.”

I

N

the morning, an incident of blackbirds happened. Swarm following swarm wheeled above Ghost Dancing and dropped into the tall oaks to watch the dawn. They seemed to be conducting some sort of ancient bird worship of the spring sun. New arrivals fluttered helter-skelter into the branches but immediately turned toward the warm light with the others. Like sunflowers, every head faced east. The birds chattered among the fat buds, their throaty squeakings like thousands of unoiled wheels. Heat-Moon says it’s the planting season when the blackbirds return; yet not long after sunrise, the warm and golden light disappeared as if the blackness in the trees had absorbed it, and it was days before I saw sun again.

To walk Main Street in Shelbyville, Kentucky, is to go down three centuries of American architecture: rough-hewn timber, postbellum brick, Victorian fretwork, 1950s plate glass. Founded in 1792, it’s an old town for this part of the country.

At the west end of Main, a man stripping siding from a small, two-story house had exposed a log cabin. I stopped to watch him straighten the doorway. To get a better perspective, he came to the sidewalk, eyed the lintel, then looked at me. “It’s tilting, isn’t it?” he said.

“There’s a little list to it, but you could live with that.”

“I want it right.” He went to the door, set up a jack, measured, then leaned into it. The timbers creaked and squared up. He shoved a couple of two-by-fours behind the lintel to hold it true then cranked down the jack. “Come in for a look,” he said. “After a hundred and fifty years, she’s not likely to fall down today.”

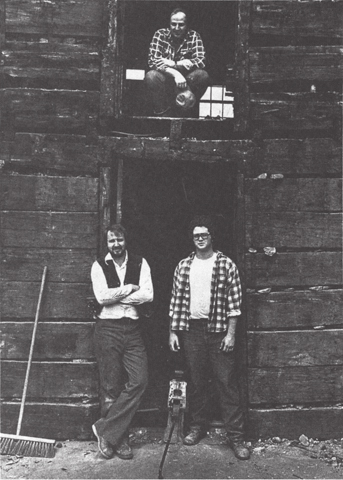

1. Bob Andriot, Tony Hardin, Kirk Littlefield in Shelbyville, Kentucky

“That’s before people started jacking around with it.”

The interior, bare of plaster and lath, leaked a deep smell of old timbers. Bigger than railway ties, the logs lay locked in dovetails, all careful work done only with ax, adz, froe, and wedge. The man, Bob Andriot, asked what I thought. “It’s a beauty. How long have you been at it?”

“Ten days. We want to move in the first of April.”

“You’re going to live here?”

“My wife and I have a picture-framing and interior design shop. We’re moving it out of our house. We just bought this place.”