Blue Angel (49 page)

Authors: Donald Spoto

At the Titania Palast: Berlin, May 1960.

Crowds with placards urging “Marlene, go home!” outside the Titania.

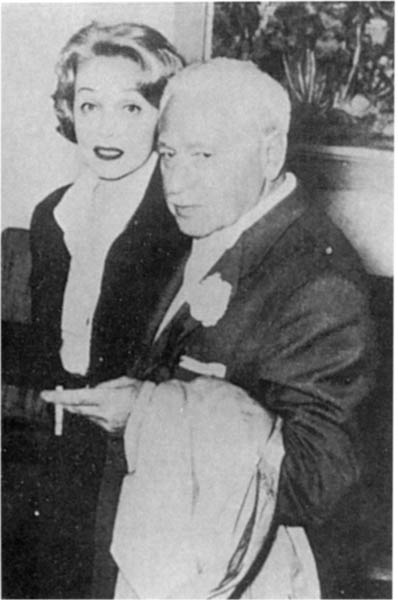

At the Locarno Film Festival with von Sternberg, July 1960.

At the funeral of Edith Piaf: Paris, 1963.

With her musical director Burt Bacharach: London, 1964.

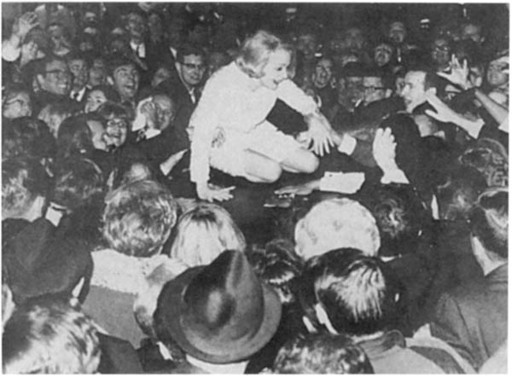

Outside the theater after the New York premiere of her one-woman show, October 1967.

On tour.

Dietrich’s last screen appearance, as the Baroness von Semering in

Just a Gigolo

, 1978.

On Sunday, May 1, a Berlin newspaper—in a triumph of Teutonic efficiency—announced the recovery of the certified birth certificate of Marlene Dietrich, who was about to step onto a German stage for the first time since 1929; she was born, the article proclaimed gleefully, on December 27, 1901.

On Tuesday, May 3, there were police precautions encircling the Titania Palast, after threats of riots, egg-pelting and a broadcast warning of the release of five hundred white mice in the theater aisles. Of two thousand seats, five hundred were empty for her premiere, but at prices ranging from two to twenty-four dollars the tickets were beyond the range of all but the most independently affluent Berliners. In her hotel room, Dietrich was moody and tense, impervious even to Bacharach’s reassurance. “I am not particularly glad to be here or there or anywhere,” she told an inquiring reporter. “All my former friends here either left Germany or died in concentration camps, and so there are none left for me to see.” She did not, she added with astonishing frankness, have any happy memories of Berlin at all.

Her attitude was, in fact, very like her act, in which Marlene Dietrich affected a stance bordering on cold contempt. Asking for nothing but attention, she offered a bluntness rarely heard from visiting performers, who ordinarily (then as later) insisted how much they loved the place they were performing in, what devoted friends and precious memories were evoked, how ineffably divine the experience was, what sheer love they felt. From Dietrich there was none of this bogus sentiment, no idle palaver. She was in a sense not ending the war once and for all, she was declaring the impossibility of a truce.

That evening, affecting a bravado she almost certainly could not have felt, Dietrich asked her driver to stop several blocks from the Titania and she walked the remaining distance. Outside the theater,

a small crowd had gathered—mostly people her own age who had seen her more than thirty years before. One woman who depended on a cane and had no ticket simply wanted a glimpse, and she quickened her step to greet Dietrich at the stage door. Her name was Mrs. Erich Ernst, and although the two women had never met, bystanders might have thought they were old friends. “Dear Marlene,” said Mrs. Ernst, “please shake my hand.” And for just the flicker of a moment, as the two women joined hands and lightly caressed one another’s cheeks, a photographer captured the image—one of them smartly dressed in a tweed coat and fashionable hat, the other wearing a faded kerchief and shawl, but both of them with tears glistening.

An hour later, the houselights inside dimmed, the orchestra struck a drumroll, and the filmmaker Helmut Kräutner introduced Marlene Dietrich as “a woman who has been true to herself.” And then a hush descended on the audience as she entered, wearing a form-fitting dress that gave not quite the provocative illusions customary in Las Vegas. There were no catcalls, no rotten fruit, no mice, no ungracious or rude reactions. The applause began politely and then, with Mayor Willy Brandt leading the ovation, there was a more enthusiastic welcome. Except for a few rowdies outside on the street, denouncing her as a traitor and holding signs demanding her immediate removal from the country (“Marlene, hau ab!—Take off, but quick”), there was nothing to suggest hostility.

With a nod of her head, Dietrich simultaneously acknowledged the welcome and cued Bacharach. And then she began to sing—first “Ich bin von Kopf bis Fuss auf Liebe eingestellt” from

The Blue Angel

—crooning for the thousandth time that she was primed for love from head to foot. For an hour, she offered her standard numbers—“Johnny,” “The Laziest Gal in Town,” “The Boys in the Back Room,” “One for My Baby,” some in English, others in German or French—but she never told the audience that she was singing just for them; she neither flattered nor appeased them, never asked or bestowed signs of false affection. Yet with each round of applause, the audience seemed more hers—even when she reminded them that she had not forgotten the past and would not repent a single moment of her decisions, a sign she gave by singing two songs

by German Jews who had fled Hitler. These she specifically dedicated to the two composers—Richard Tauber (“a wonderful human being,” she said) and Friedrich Holländer, who had written the majority of her movie songs. There was only silence in the Titania when she announced these songs, but no mention of this at all in the overwhelmingly favorable reviews next day.

The theater was only three-quarters full (and half of those had been admitted on free passes), but the fifteen hundred spectators sounded like thousands. After her final number—a wistful rendition of a sentimental ballad called “I Still Have a Valise Left in Berlin” she delivered in her white tuxedo—Mayor Brandt rose to his feet, leading a thunderous eleven curtain calls.

“She won her battle from the first moment,” proclaimed

Der Abend

next day. “She stood there like a queen—proud and sovereign. According to the

Bild-Zeitung

, “Marlene came, saw and conquered,” to which the

Berliner Zeitung

added heroically, “She is not only a great artist, she is a lovable woman—she is one of us. Marlene Dietrich has really come home!”

Less grandly, an elderly lady leaving the theater had said to her companion, “That’s the old Marlene.”

Of course it had not been the old Marlene at all—neither the saucy chorine, the plump, bored repertory player, nor even the innocent destroyer of

The Blue Angel

. But there was something of the past for those who ransacked memories or longed for reconciliation. Dietrich’s now deep and reedy voice, to those who wanted to hear it so, was lined and sealed with recollections of a distant time, before an ocean of rancor and resentment separated her from Berlin. No matter how much had changed there, she had indeed come home. Without any counterfeit sweetness or phony tenderness, and after a mere one hour of song, she had rediscovered her lost role as a proud Prussian commanding both the stage and her hearers—courageous, insistently autonomous and, as her introducer had said, true to herself. To postwar Berlin, ringed with a wall, with fear, suspicion and remorse, she could have offered no greater benediction.

*

“The Danger of Being Beautiful” was the apt title for a shallow, impersonal interview for

McCall’s

in March 1957, in which Dietrich discussed old-fashioned feminine wiles.

*

In her memoir, Dietrich claimed that the idea of winning an Oscar for

Witness

meant “nothing at all to me” (

Marlene

, p. 128).