Blue Angel (48 page)

Authors: Donald Spoto

In fact the pretour publicity then being generated was a horror, and it was much to Dietrich’s credit that she ignored the threats of danger and pressed on; she could, after all, have easily substituted engagements elsewhere. “If they had any character,” she had said in 1952, “the German people would hate me [for my entertainment of Allied troops].” Eight years later, that torn and divided land had “character” aplenty, but much of it was harnessed against Dietrich from March to the end of April, as warnings and vilifications filled the German press:

—“The USA and Germany are long since friends, but Dietrich is still leading a private war against the fatherland she unnecessarily gave up. Obviously she does not despise the Deutsch Mark as much as her homeland.” —

Kölnische Rundschau

(Cologne), March 3.

—“Who has invited this person who worked against us during the war to perform as a visiting actress? Marlene, go home!” —

Bild-Zeitung

(Berlin), March 3.

—“Marlene marched on the side of the Resistance fighters and the enemies of everything that was Germany. She did not keep still when Germans tried to dig themselves out of the ruins and misery and regain respect in the world. It would be better for us if she were to remain where she is.” —

Badische Tagblatt

(Baden-Baden), March 24.

—“She donned an Allied uniform and entertained their troops! While her actions can be understood during the Hitler regime, it is incomprehensible why she refused to change her mind after the war.” —

Bild am Sonntag

(Hamburg), April 3.

There was some (but not much) dissent: “If she is received with tomatoes and rotten eggs,” warned Hamburg’s

Die Welt

, “then our reputation in America will decline further, and it will prove anew that we have learned nothing from our mistakes.” And newspapers did receive a few letters like that from a woman in Düsseldorf: “Who showed more character—Marlene, who resisted all enticements to turn to Hitler and who fought uncompromisingly against criminal Nazi Germany, or we who went down on our knees before those wretched leaders? It’s not a very far journey from ‘Jews, get out!’ to ‘Out with Marlene!’ ”

But support for the returning Dietrich was essentially as flimsy as the chiffon of her gowns. As the date of her arrival drew near, letters to editors proliferated and privately circulated handbills opposing her littered every major German city:

—“An impudent wench fights for her honor by daring to come home. Dietrich has thousands of German soldiers’ graves on her conscience. She not only fought the Nazis but the German people as well! Now she is even enlisting help from Willy Brandt [mayor of West Berlin], the former resistance fighter. She is an antisocial parasite and should receive deserved punishment from us.”

—“Aren’t you, a base and dirty traitor, ashamed to set foot on German soil? You should be lynched, since you are the most wretched war criminal.” —Open letter from Mayen.

“The major error of this tour,” said the respected Belgian critic Jean Améry years later,

is that she thought she was returning home triumphantly. What she did not take into account was the unexpected self-assurance of the German citizenry and especially of West Berliners. With the economic recovery of Germany, people had regained their good conscience. And a new generation had grown up, too, for whom Dietrich meant very little—as the ghosts of Nazism meant very little to them.

The outcry against her return increased when Dietrich’s earlier unambiguous comments on Germany were loudly broadcast: “I was German but I refused to declare myself a supporter of a country in which such atrocities were taking place.” And when asked that spring whether she felt any sentiment about returning to her former home she replied coldly, “Not one bit. I gave up my fatherland because I was ashamed of it. Home is where my family is, and my family is in America.” Far from attempting to reconcile herself with her country, her return seemed more an act of defiance.

But Dietrich was not, nor had she ever been, ranked as a political person exploited as a German national or, later, as a naturalized German-American. At stake in 1960 was her adherence to a moral position from which she had never wavered a quarter-century earlier, when many of her compatriots were not at all convinced that Hitler was so bad after all. (“If I were a German,” added Améry, “I would be proud of her—and of her pride.”)

O

N

A

PRIL

30, 1960—

FIFTEEN YEARS AFTER HER

last visit—Marlene Dietrich arrived in Berlin, and on May 2 she strode into a hotel dining room and answered journalists’ questions in flawless, elegant German. Wearing the red ribbon of the French Legion of Honor and carrying a bouquet of lilies of the valley, she stared around, then sat down and spoke with remarkably cool assurance: “I am singing here because singing is my business, and I have been asked by my German agents to come. Why should I say no? . . . Am I afraid of rotten tomatoes? No, rotten eggs would be worse, because they could not be cleaned from my swansdown coat . . . Perhaps I will do some good, you say? I don’t want to do any good.” She felt, she told a friend that evening at the Berlin Hilton, “as though I’m going to my Nuremberg trial when I step out on that stage tomorrow night.”

With Danny Thomas, about 1949.

With Ernest Hemingway in New York, 1947.

With Maria in New York, 1950.

Opening night in Las Vegas, 1953.

London, 1954.

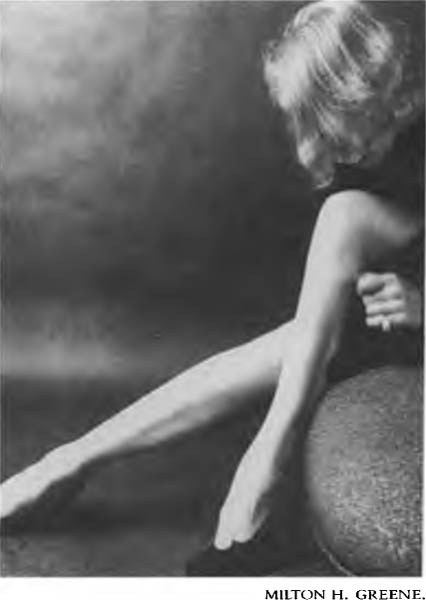

The famous legs, celebrated by photographer Milton Greene in 1955.

During filming of

Witness for the Prosecution

, with Charles Laughton, Tyrone Power and director Billy Wilder: Hollywood, 1957.

With Noël Coward, 1958.