Blow Out the Moon (17 page)

Emmy and Bubby came running up.

“Did you put that hen in the drawer?”

Emmy nodded.

“What on Earth did you do that for?” I said.

Emmy and Bubby giggled, and I realized I DID sound sort of too English — like a schoolmistress! I hadn’t been trying to sound English; when I first went to Sibton Park, I did try with my accent — very hard; but now, I didn’t have to try. I just sounded English.

But I really was curious.

“Why?” I said. “Why did you do it?”

“I thought it would be nice for Philip to have another bird’s company,” Emmy said. “Someone to talk to.”

Of all the idiotic reasons!

“Couldn’t you just have brought HIS cage out here?”

“I didn’t think of that.”

Then Bubby said something in their chicken language, and they went on with their game, whatever it was.

I went back inside and found Veronica.

“Was your mother VERY cross about the hen?”

“More startled,” Veronica said. “She’s not used to American children. How would you like to go to the seaside today?”

American

children! As though we were worse than other kinds! And her mother DIDN’T like having us there.

I decided that when I grew up, I’d never make guests feel unwelcome, even if they were — especially if the guests were children from another country.

But

Veronica

liked us, especially me. She had stuck up for us, too.

“That sounds fun,” I said, trying to sound like it would be.

I knew what the English beach was like: cold, with gray, not blue, water and tiny waves. Instead of sand there were little pebbles — but still, it was the ocean!

When we got there, Veronica told us that waves with white curling tops are called “prancing ponies.” Emmy and Bubby loved that.

They ran up to the little waves holding hands and then, shrieking and giggling, ran away from them. I was about to dive in (I love to swim) when Veronica said, “Oh, look! A wishing pebble!”

She picked up a pure white — almost transparent — pebble.

“When I was a child, we believed that you could make wishes on white stones.”

“One wish for each stone?”

She nodded.

“You throw the stone into the sea and make a wish.”

I decided to find a white stone and wish to go back to America. In Cornwall, my father had talked a lot about how much he loved London and what a “great life” it was for them and for another American couple they knew. My mother didn’t say anything until he used this couple as an example. Then she said: “Yes, it’s a great life for Helen — lugging the coal scuttle up from the basement!”

It sounded as though she didn’t want to stay, either, but I was still worried. I liked Veronica, and lots of things in England were interesting and fun, but I didn’t belong here.

So, I looked for white pebbles. The sun came out for a minute, and the pebbles all shone — there seemed to be quite a lot of almost white ones. The others were holding hands and trying to jump over the waves, but I kept looking for white pebbles.

I found one and ran to the water. I faced west, where America was, thinking of a long, straight line, with me at one end and America at the other. Then I threw the stone into the gray water, straight towards America, towards Henry and home, and wished.

Back at Sibton

But when I got back to Sibton Park for Autumn Term, we were all a little bit excited to see each other again, and I was extra-excited because I’d done so well in all my subjects, including French, that I was going to be in IIA, not IIB! Then, when we were in the cloakroom changing into our house shoes (it was one of those warm fall days and we’d been playing outside), something even more exciting happened.

I was on the floor tugging off my Wellingtons when someone came running in shouting, “We’ve got a study! IIA has its own study!”

We’d never had a study before, only the older girls had them. I’d never even been in one — they’re private, that’s the whole point. In school stories they have fireplaces and the girls roast chestnuts and make tea and have little parties in them.

Wellingtons

“Hooray!” I said.

That sounds fake, but it’s the kind of thing people say in England when they’re happy. It didn’t SOUND as happy as I felt, though, so I kicked my Wellington the rest of the way off — off, and up in the air — hard.

It flew up and then out through the (closed) window, smashing the pane completely.

Everyone kind of gasped.

I stood up.

“Where are you going?” Clare said.

“To own up, of course,” I said.

She gave that little Clare half smile — as though something was amusing.

I didn’t find Marza, but I did find her mother, an old lady we didn’t see much who always wore black dresses down to her ankles. I told her my name and then what I had done. She said, “I’m sure Marza will understand.”

She didn’t.

About half an hour later, she sent for me. When I went into her office she was sitting up very straight, as usual. (She told us once that her posture was so good because when she was a girl they had to wear special things on their backs to MAKE them straight. Hers had worked, I guess: I never saw her back touch a chair.)

She just looked at me without saying anything for what felt like a long time. I could see that she was quite cross. When she asked me how I had broken the window, her voice sounded a little like all the mothers in America when these things happened and they said things like, “What were you doing with the record on your head, Libby?”

But when I’d finished talking and Marza said, “That wasn’t very sensible, was it?” I minded. I admired Marza.

Then she asked me, sounding kind of curious, why I had done it.

“I was just so excited about our getting a study,” I said, and that sounded feeble (that’s what they say in England — it’s a good word, I think) even to me.

She said that when “one” did things that were “foolish or unguarded” or “thoughtless,” someone else usually had to “bear the consequences.” In this case, she said, someone else would have to mend the window. She also talked about being “sensible” and “careful.”

“You have high spirits,” she said (and the way she said that made it sound as though high spirits weren’t a bad thing to have), “but you must learn to be sensible and have self-command or your heedlessness will be a source of grief to you as well as to others.”

That was probably true, I thought.

“I will,” I said. “Well, I’ll try.”

“Very well then, off you go.”

When she said that, she didn’t sound so cross. I

would

try, I thought.

Trying

I started trying right away.

On the first day of lessons, Miss Tomlinson, the teacher, put me in the first row, the row closest to her desk. IIA’s class and classroom were bigger than IIB’s, and everyone was my age or older. Some of the girls in the back looked a lot older; at least, they were a lot bigger.

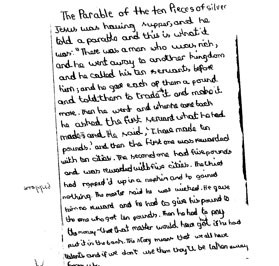

Lessons started the same way, with Scripture; but instead of telling us what chapter to do, Miss Tomlinson said, “From now on, instead of just describing what happens in the chapter, you’re to explain what it means.” Some people looked a little confused. “Just write what the chapter says, as usual, and then explain the meaning. You’ll need to think a bit.”

She smiled when she said the last part, and then told us to go to Luke, Chapter 19. I read the chapter quickly — I always like reading and writing, and I liked the idea of saying what we thought it meant. I read the chapter and I thought I really DID know what it meant.

Eagerly, as fast as I could, but in my best handwriting, I wrote:

Miss Tomlinson corrected our Scripture while we did our arithmetic.

Then, looking annoyed, she said only one person had done her Scripture properly. “And on her very first day, too.”

I was the only new person, so it must have been me. Everyone looked at me, some people not in a very friendly way — a girl in my new dormitory, Jennifer Dixon, looked especially cold. (My new dormitory was called Florence Nightingale. Brioney was still in the Night Nursery, with other younger children, but I was in Florence Nightingale and everyone in the dormitory was in IIA: Clare, Veryan, Jennifer Dixon, and me. I was in a dormitory AND a class, IIA, with the other people my own age.)

I felt relieved that I would be able to do the lessons, and a bit odd: a teacher had never said anything good about me before. A bit odd is the English way of saying it, but that’s how I thought by then; now, I would say it felt strange and a little uncomfortable, but nice, too. That made me want to try even more.

FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE was a famous English lady and nurse. She was called “the lady of the lamp” because she carried a lamp around a hospital in one of the English wars — but she had also STARTED the whole hospital. Before that, they didn’t have hospitals for the wounded soldiers.

Once, a man in the government had said, “It can’t be done,” and Florence Nightingale just looked at him calmly and said, “But it must be done.”

The man said he never forgot the force of those words. And whatever it was got done.

The rest of the lessons were just as interesting as in IIB, and harder. We read Shakespeare. I said I didn’t see what was so great about him; Miss Tomlinson said I would understand when I was grown up. She seemed to find my comments more interesting than Miss Davenport had (maybe Scripture got things off to a lucky start?).

The coats, but not the hats, we wore: This is from a recent school catalog.

Now when we went to church we wore brown-and-white checked coats and brown velvet hats and brown wool gloves, and sat as close together as we could. I still thought church was boring, but I tried to understand what it was all about.

I knew the words of all the prayers and hymns. Usually the hymns were quiet. Often they had something in them about Jesus being crucified — nails in his ankles and arms and a crown of thorns on his head. All that blood and suffering, and prayers about miserable sinners — I didn’t like that at all.

There were some happy hymns, and I liked them:

All things bright and beautiful

All creatures great and small

All things wise and wonderful

The Lord God made them all.

Each little flower that opens

Each little bird that sings

He made their glowing colors

He made their shining wings.

This hymn had one verse that I didn’t like:

The rich man in his castle

The poor man at the gates

God put them in their places

And ordered their estates.

That was the bad side of England — what the Revolution stopped in America — but they still had it in England. It reminded me of someone’s father saying indignantly, “ … when a shopkeeper starts thinking he’s your equal!”

There were some quiet hymns I liked. One began:

For the beauty of the earth

For the blessings of the field

…

The earth IS beautiful — around Sibton Park it was, anyway; why couldn’t all the hymns be about that? Another one was about England’s “green and pleasant” land and “clouded hills.” That IS what England looks like (“clouded hills” always made me think of the horses’ meadow, sloping up to trees at the top), so I liked it, too.