Blow Out the Moon (14 page)

The partners would walk to church together and sit next to each other. The idea was that the senior would make the junior behave.

Sisters, Marza had said, could be partners. So Retina picked Brioney, and Carol picked Clare. The head girl, Alice, walked up to Veryan and nodded: Of course, she would pick Veryan — she was Veryan’s favorite senior. At Sibton Park it was the custom for each senior (girl in the Upper School) to look after a junior (a girl in the Lower School) not all the time, but when someone older was wanted. All the juniors who didn’t have older sisters at the school had a senior who did this.

If, for example, Veryan was upset, we would go get Alice and she would come down to the Night Nursery and talk to Veryan. Matron, I guess, was the one who did this for me, though the only time she’d ever had to was the time I fell out of the tree. So I didn’t know who would pick me.

Another prefect did: a girl called Buffer. She frowned and then nodded at me. I’d never talked to her before, but I knew who she was, and I stood on line next to her.

When everyone had a partner, we walked out of the school in what they called a “crocodile” (a line), two by two.

I knew that Buffer’s real name was Elizabeth since there were so many Elizabeths in the school they all had nicknames — but I don’t know why her nickname was Buffer. She was tall, with gray eyes and brown hair cut straight across her forehead, like mine! Only her hair was much thicker and much neater. She was a lot bigger than I was, but most of the seniors were.

In school stories, the prefects were in charge of things like making people go to bed on time; at Sibton Park, they were just older girls Marza picked to be prefects. There were four.

Even though Buffer took long steps, she was kind of a slow walker, and I walked a little in front of her, turning around or walking backward to look up at her.

She seemed very serious. She didn’t talk much on the way to church; I did. I think I talked the whole way without stopping. Every now and then she’d give a sudden laugh and then (just as suddenly) her face would get serious again.

I always liked the walk to church: It was along lanes with wide strips of grass on each side — that rich English grass that feels springy under your feet. I don’t really remember what I talked about — whatever I was thinking or noticing, probably; I didn’t really pay much attention to what I was saying.

I do remember that just before we got to the church the air suddenly smelled almost sweet, in a way it never had before, and I said, “What’s that beautiful scent?”

“Lavender,” she said. “It grows in the churchyard.”

Maybe you’ve smelled lavender soap? This smelled drier and sunnier — that scent seemed all mixed up with the sun and Sunday and summer.

The church was gray stone, very old, and inside, cold, even that day. Banners that people had carried in real wars hung on the walls.

Church was the only time at Sibton Park that I was bored. Of course, we weren’t allowed to talk; we weren’t allowed even to read the other parts of the prayer book or the words of the other hymns. We had to just look at the page in the book that we were on. Sometimes hymns are loud and fun, but if we sang too loudly in church, Marza got cross (the Sunday before we’d really bellowed “Onward Christian Soldiers”).

The only things to do in church were say the prayers, sing the hymns, and think.

After church, we went to our form rooms to write our letters to our parents. If you were a junior, your form mistress read your letter and corrected any mistakes; you wrote it over if there were any and then she read it again. When it was passed you could play until dinner time. No one read the seniors’ letters.

That Sunday I wrote two letters, one to Emmy and one to the rest of the family. But first, I reread their letters to me: My mother had already written me twelve letters, and Emmy had written me one. Willy and Bubby each sent a letter, too, but not real letters — Bubby’s was pretend writing (two pages of scribbles about the size of letters) and Willy’s was a picture with his name in capital letters and X’s for kisses.

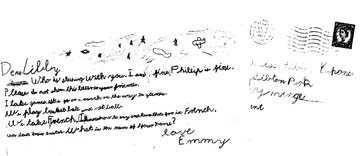

This is Emmy’s letter; she drew a picture on the back of it, too.

Philip was the pet budgerigar they had promised her — my mother had written to me about getting him, and that they had started a new school.

I had written to her first:

Dear Emmy,

I’m having a wonderful time. You are allowed to go into the fields and pet the horses. I wish you were here with me. It isn’t very long until May 16th. There are four children in my dormitory counting me: their names are Clare, Veryan, and Brioney. If you came you would be in the 1st form. I am in 2B. I would be in 2A probably if it wasn’t for my French. What are you doing? Are you smart in school? Can’t wait until May 16th.

Love, Libby.

My mother’s last letter was:

Dear Libby

—

We all hope you are having a good time.

Great excitement here this week as Emmy and Willy started their new school, and guess who else did? Bubby! Bubby will go only in the mornings. Emmy and Willy will have every Wednesday afternoon as a half-holiday, and their half-term holiday will be the same as yours. They all enjoyed school; liked their teachers and the other children. It’s a very nice school and I think all three will learn a lot and have a good time, too.

Have the clothes we ordered arrived yet? You should be receiving your riding clothes, ballet tunic, mac, and another skirt. When we come to visit you, we can bring along anything you may have forgotten to pack if you will let us know what you want. Will bring along your other jumper, too. Are your pajamas warm enough, Libby?

Bubby considers herself quite grown up now that she has started school. She was very shy about going into her classroom the first day, later told us she had played with plasticene, gone out in the garden, taken a rest, listened to a story, and played with a horse.

Be sure to let us know if there is anything you need or want, and we can bring it when we come to see you on the 16th. Love from all of us, dear.

Mother

I wrote this to everyone else:

Dear Mother and Father and Willy and Bubby,

How are you? Mo says Bubby’s writing looks exactly like Persian. So Bubby may be writing in Persian and we don’t know it! We have lessons on Saturday until 12:30. Are you pleased with how smart Emmy is? At night we play a game called Hospital. We made it up. We use my nail set for the doctor’s tools. The operation we did last night was appendix. With a blunt thing we poked around, with the sharp one we gave shots, one that is like a scraper we use to open the skin. With the tweezers we take out the appendix, with the nail file we take the patient’s temperature and with the scissors (the handles of them) we sew it up. The title of the hymn book I need is The Common Prayer Hymns Ancient and Modern. When will my riding clothes be ready? Give my love to everyone.

Love, Libby.

Then I put some kisses and hugs at the bottom. I would be seeing them on Saturday, May 16th, one day less than two weeks away — not VERY long.

My First Riding Lesson

Finally my riding clothes came: thick brown jodhpurs, a tweed jacket, string gloves, and a hard hat. I didn’t need boots — most juniors rode in their walking shoes.

I was VERY excited. In my class were Brioney, someone who was only five, and Clare. They had all ridden before — quite a lot — and Clare had real jodhpur boots.

Clare on Frisky. They are in the stable yard; Miss Monkman is in the stable doorway.

We started in the stable yard — I had Tuppence. Miss Monkman showed me how to get on (it was much easier with a stirrup and saddle), and she made the stirrups the right length and put my feet in them; she pushed my heels down and told me to keep them down. She pushed my lower legs back a bit and pressed my knees into the saddle, and then she put my fingers around the reins, so that my two fists were facing each other with the thumbs on top, and the bottoms of my fists were pressed into Tuppence. She said, “Whatever you do, don’t let go of the reins — even if you fall off.”

She glanced at the others, told Brioney to shorten her stirrups, and then, with Tuppence’s reins in one hand, she led us out of the stable yard. We walked down the road, through the cow pasture, and into the horse pasture, with Miss Monkman holding my reins and talking to me the whole time. Finally when we got to the paddock, she let go of the reins and let me ride by myself.

I was really riding. I was on a horse, I could feel it moving underneath me, and see its mane kind of flapping up and down, and its ears flickering back and forth — listening, maybe wondering who I was.

I tried to keep the reins where Miss Monkman had put them: in my fists, with my thumbs on top, and the bottom of my hands on the pony’s withers (two bumpy bones right in front of the saddle). I held my hands still, so I wouldn’t hurt Tuppence’s mouth — Miss Monkman told me that, and I remembered what

Black Beauty

said about the bit, too. I pushed my toes up and my heels down.

I gripped with my knees. I sat up straight and looked straight ahead, between Tuppence’s flickering ears, keeping my elbows pressed to my sides.

I could do all those things at once while we walked.

Then Miss Monkman, who was standing in the middle of the paddock while we rode round her, called, “Trot!” and all the horses went faster and Tuppence did, too. I bumped up and down, wobbling all over the place and almost losing my balance — my arms went out, my hands jerked off the withers and into the air; but I didn’t let go of the reins.

“Libby, grab the saddle or a bit of mane if you feel yourself losing your balance! Sit up straight!” Miss Monkman shouted. “Keep your hands on the withers!”

I tried to but I kept bumping up and down and so did my hands.

“Heels down, Libby — it’s easier to balance that way!” Miss Monkman said. “Post.”

(That means watch the outside shoulder — when it goes forward, push yourself up. You can pretend there’s a string from the horse’s shoulder to the middle of your belt, pulling you up and forward. Miss Monkman had explained all that but it’s hard to do.)

“It’s a RHYthm. ONE two, ONE two. Up! Down! Post — one, two! One, two! Up, down! Count with me, come on.”

I watched and counted — ONE two, ONE two — but I still bumped. Once or twice I did actually post in rhythm — I think, I’m not sure. Most of the time I just jostled around, but I did stay on.

There was so much to think about and try to do all at once. Riding was MUCH harder than I expected; the only thing that was easy was sitting up straight.

The next day my bottom and the inside of my thighs hurt quite a lot. I asked Clare about it.

“You’re saddle-sore,” Clare said. “It’s because riding is new to you.”

“I’m not very good at it,” I said.

“You will be once you can post,” she said. I asked how long that would take. She said, “Posting is a bit like riding a bicycle — one day you just do it and after that you always know.”

I tried to remember how long it had taken to learn to ride a two-wheeler, but I couldn’t; and riding a horse seemed much harder. But I’d learn.

May 16th

On Saturday, May 16th, right after lessons, I waited in the corridor by the Tudor Garden: this was where people always waited for their parents when they were being taken out. I knew that because lots of people already had gone out. It was only in your first term that you weren’t allowed to see your parents for the first six weeks.

There was a door with glass panes at the top: You could see the Tudor Garden and beyond it, the front drive.

I waited and waited, listening for a car. I had written them where I would be waiting, and written them again on Wednesday to remind them of the date and time.

While I was waiting, Sarah Riley came by and asked me what kind of car they had.

“I don’t know,” I said. She looked surprised, and I added, “It’s a different one every time they go someplace.”

“Oh, you hire a car, do you?” she said — she sort of drawled the words and pronounced “hire” as though it was “har” in a way that made me uncomfortable.