Bloody Crimes (35 page)

The embalmer opened the coffin and judged the body ready for viewing. According to one sympathetic chronicler of the ceremonies, “the features were but slightly changed from the appearance they bore when exposed in the Capitol at Washington.” But the journey had begun to take its toll on the corpse. Lincoln’s face turned darker by the day, and the embalmer tried to conceal this with fresh applications of chalk-white potions. All through the day and night the people came, one hundred thousand of them, before the gates to the

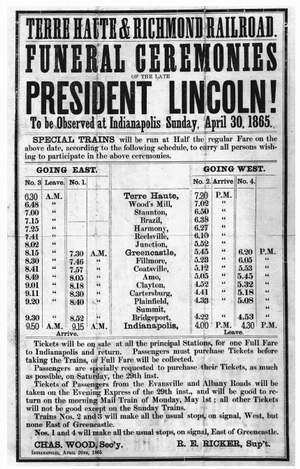

IN CLEVELAND, CROWDS WAIT TO VIEW LINCOLN’S CORPSE IN THE CELEBRATED “PAGODA” PAVILION.

square were shut at 10:00 p.m. The coffin was closed at 10:10 p.m., and one hour later it was carried to the hearse.

Just as Lincoln’s remains departed the scene the rain, which had been heavy throughout much of the day, turned into a torrential downpour. The water spoiled the decorations, and the mourning crepe cried streaks of black tears. From the railroad station Townsend telegraphed Washington at 11:30 p.m., Friday, April 28: “The funeral train is ready, and will start at midnight.” A

New York Times

correspondent confirmed Townsend’s earlier observation that something was happening as the train continued west: “Everywhere deep sorrow has been manifested, and the feeling seems, if possible, to deepen, as we move Westward with the remains to their final resting place.”

The downpour lasted for most of the night as the train steamed from Cleveland to the Ohio state capital, Columbus. But the foul weather could not deter the people from turning out along the tracks. According to one contemporary account, “Bonfires and torches were

lit, the principal buildings draped in mourning, bells tolled, flags floated at half-mast, and the sorrowing inhabitants stood in groups, uncovered and with saddened faces gazing with awe and veneration upon the cortege as it moved slowly by.”

Five miles from Columbus, the passengers witnessed a pitiful tribute that stood out in stark contrast to all the elaborate, official processions and ponderous orations that had gone on before. Those who saw it were taken aback by its heartfelt simplicity: “An aged woman bare headed, her gray hairs disheveled, tears coming down her furrowed cheeks, holding in her right hand a sable scarf and in her left a bouquet of wild flowers, which she stretched imploringly toward the funeral car.” Her gesture was as eloquent as a cannonade of one hundred minute guns, the tramp of one hundred thousand mourners marching through the great cities of the North, and as richly decorated hearses and death chambers. Abraham Lincoln would have noticed her. She was an eerie reminder of his aged, pioneer stepmother, who had survived him and awaited his return to the prairies. “I knowed when he went away he’d never come back alive,” she’d said upon hearing of the assassination.

The train pulled into the Union Depot at Columbus early on Saturday, April 29. It was as it had been in Cleveland: a reception committee of elected officials, military officers, and leading citizens; an escort to the capitol building by a massive military and civic procession; and lying in state in another death chamber bedecked with the now predictable and overflowing quantities of flowers and mourning decorations. Lincoln’s bearers removed his coffin and placed it in yet another fabulous hearse, this one topped with a canopy that resembled a Chinese pagoda. The organizers back in Cleveland must have taken that as a tribute to their unforgettable pavilion. The hearse drove off to the state capitol and at 9:30 a.m. Lincoln’s coffin was laid upon the catafalque. As usual, the president’s honor guard left behind on the train the smaller, second coffin that had accompanied Lincoln’s in the presidential car from Washington.

In the press accounts of the funeral pageant, little mention was made of Willie Lincoln. His coffin was never unloaded from the train. He did not ride in the hearse with his father in any of the funeral processions. His closed coffin—he had been dead for three years—did not lie next to the president’s at the public viewings. The national obsequies were for the head of state. But in Columbus, Willie Lincoln was not forgotten. General Townsend was the recipient of the gesture: “While at Columbus I received a note from a lady, wife of one of the principal citizens, accompanying a little cross made of wild violets. The note said that the writer’s little girls had gone to the woods in the early morning and gathered the flowers with which they had wrought the cross. They desired it might be laid on little Willie’s coffin, ‘they felt so sorry for him.’ ”

Of the dozens of mourning songs composed for Abraham Lincoln, only one of them, “The Savior of Our Country,” was dedicated to “little Willie.” The lyrics described an eerie, father-son reunion in heaven.

Father! When on earth you fell Father! Was my mother well?

When I fell your Mother cried! Then unconsciously I died.

Glory forms our sunlight here! Astral Lamps our Chandelier!

Rode you here among the stars, In a train of silver cars!

Willie! On the earth look back! Father! Tis a speck of black!

Robed in Mourning as you see! Mourns the Earth for you and me!

God is Father! God is dear! May I have two Fathers here?

Father! On our Golden pave Gingles something from your grave!

Willie! Yes, Four Million Chains, Bring I here where Justice Reigns.

From the Land your Father saves! Chains that bound Four Million Slaves!

Willie! On the earth look back! Father! Tis a speck of black!

Robed in Mourning as you see! Mourns the Earth for you and me!

But the song was wrong. If Willie had looked down from heaven upon the earth, he would have seen, through the night sky, not only a dim “speck of black.” He would have seen a ribbon of flame unspooling across the land as torches and bonfires marked his and his father’s way home.

O

n April 29, Davis crossed the Saluda River at Swancey’s Ferry, South Carolina. Federal cavalry had a difficult time picking up his trail. Southerners tried to thwart the president’s pursuers. One Yankee cavalryman complained: “The white people seemed to be doing all they could to throw us off Davis’ trail and impart false information to their slaves, knowing the latter would lose no time in bringing it to us.” Later, reports by blacks to Henry Harnden, First Wisconsin Cavalry, and Benjamin D. Pritchard, Fourth Michigan Cavalry, led them directly to the Davises.

General James Wilson outlined his plan for the pursuit. He did not single out one particular unit to capture Davis. Instead, he planned to flood a whole region with manhunters to increase the chance that one unit among many might catch Davis in the net. “Soon after I heard that Johnston had surrendered to General Sherman…I received information that Davis, under an escort of a considerable force of cavalry, and with a large amount of treasure in wagons, was marching south from Charlotte, with the intention of going west of the Mississippi River,” Wilson reported. He set a number of units in motion with the hope of intercepting Davis at any point he might attempt to pass through Union lines.

Georgia was now the focal point. Wilson knew that after Davis left Charlotte, he would not turn west or east and risk remaining in North Carolina. Those routes would not lead him to the banks of the Mississippi River or to a safe ocean port. The Union had locked down North Carolina’s Atlantic coast. Turning west or east would bring Davis into contact with federal troops. There was only one place to go—down through South Carolina and into Georgia—and General Wilson knew it:

I immediately directed Brevet Brigadier General Winslow, temporarily in command of the Fourth Division, to march to Atlanta, and from that place watch all the roads north of the mouth of the Yellow River, to send detachments to Newman, Carrollton, and Talladega, as well as to Athens and Washington. Brigadier General Croxton, commanding First Division, was directed to picket the Ocmulgee from the mouth of the Yellow River to Macon, to send his best regiment to the east of the Oconee, via Dublin, with orders to find the trail of the fugitives and follow them to the Gulf or the Mississippi River, if necessary. I directed Col. R. H. G. Minty, commanding the Second Division, to picket the Ocmulgee from [Macon] to Hawkinsville, and the 6th to extend his line rapidly down the Ocmulgee and Altamaha as far as the mouth of the Ohoopee. He also sent a force to Oglethorpe to picket the Flint River and crossings from the Muscogee and Macon Railroad to Albany, and 300 men to Cuthbert, to hold themselves in readiness to move in any direction circumstances might render advisable. A small detachment of men was also sent to Columbus, Georgia.

Wilson also alerted troops in Florida, in case Davis was able to slip through Georgia and make a run for the coast and escape the United States on an oceangoing vessel:

General McCook, with 500 men of his division, had been previously ordered to Tallahassee, Florida, for the purpose of receiving the surrender of rebel troops in that State. A portion of his command at Albany was directed to picket the Flint River thence to its mouth. He was instructed to send out small scouting parties to the north and eastward from Thomasville and Tallahassee. The troops occupied almost a continuous line from the Etowah River to Tallahassee, Florida, and the mouth of the Flint River, with patrols through all the country to the northward and eastward, and small detachments at the railroad stations in the rear of the entire line. It was expected that the patrols and pickets would discover the trail of Davis and his party and communicate the intelligence by courier rapidly enough to secure prompt and effective pursuit.

I

n Columbus, former Ohio congressman Job E. Stevenson delivered a memorial address at 4:00 p.m. that was unlike any other given in any city since the train had left Washington. It was a unique cry for vengeance. Stevenson accused the South of many crimes and warned that its people must suffer justice. He proclaimed:

But he was slain—slain by slavery. That fiend incarnate did the deed. Beaten in battle, the leaders sought to save slavery by assassination. Their madness presaged their destruction…They have murdered Mercy and Justice rules alone…They have appealed to the sword; if they were tried by the laws of war, their barbarous crimes against humanity would doom them to death. The blood of thousands of murdered prisoners cries to heaven. The shades of sixty-two thousand starved soldiers rise up in judgment against them…Some wonder why the South killed her best friend. Abraham Lincoln was the true friend

of the people of the South; for he was their friend as Jesus is the friend of sinners—ready to save when they repent. He was not the friend of rebellion, of treason, of slavery—he was their boldest and strongest foe, and therefore they slew him—but in his death they die; the people have judged them, and they stand convicted, smitten with remorse and dismay—while the cause for which the President perished, sanctified by his blood, grows stronger and brighter…Ours is the grief—theirs is the loss, and his is the gain. He died for Liberty and Union, and now he wears the martyr’s crown. He is our crowned President…Let us beware of the Delilah of the South.

At 6:00 p.m. the doors to the capitol were closed and a procession escorted Lincoln’s body back to the Great Central Railway depot. At 8:00 p.m. tolling bells signaled the train’s departure from Columbus. It steamed west through Pleasant Valley, where giant bonfires lit up the country for miles; Unionville; Milford; Woodstock; Urbana, where illuminated color transparencies hung from the arms of a large cross; Piqua, where ten thousand people assembled close to midnight; Covington; Greenville; and New Paris, where more giant bonfires lit the sky.

The cortege crossed into Indiana in the middle of the night. At 3:10 a.m. on Sunday, April 30, it rolled into Richmond, the first town across the border. Despite the late hour, city bells rang and twelve thousand people turned out to watch the train pass under an impressive arch twenty-five feet high and thirty feet wide, while a woman costumed as the Genius of Liberty, flanked by a soldier and a sailor, wept over a mock coffin of Lincoln. The train stopped long enough for a committee of ladies to come aboard and place a floral wreath on each coffin. The motto on Willie’s tribute read: “Like the early morning flower he was taken from our midst.” All through the night, on the long, rural stretches of open country between the towns, farmers kept watch. The

Indiana State Journal

reported: “All along the line