Bloody Crimes (54 page)

The Lincoln bibliography, more than fifteen thousand titles, dwarfs the literature on Davis. Lincoln is served by a cottage industry that produces dozens of books, articles, conferences, and lectures every year. There is no Davis cottage industry. The one exception is the

Papers of Jefferson Davis

project, a labor of love and of exquisite scholarly merit. But these volumes are purchased by historians and libraries, not the general public.

What explains the rise and fall of Davis in American popular memory? He lost, and history tends to reward winners, not losers. But there must be more to it than that. Perhaps it comes down to the slaves, the song, and the flag. The Confederate past is controversial. In the spring of 2010, on the eve of the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, the governor of Virginia created a furor by proclaiming Confederate History Month, a celebration condemned by some as, at best, insensitive and, at worst, racist. A historical figure who owned slaves, wished he “was in the land of cotton,” and waved the Stars and Bars must today be rebuked and erased from popular memory, not studied. Better to forget. Perhaps, someday, someone will demand that his statue be banished from the U.S. Capitol.

In Richmond, the Confederate White House and the Museum of the Confederacy, two of the finest Civil War sites in the country, are in trouble. Once central to that city’s identity, they languish now in semi-obscurity, overshadowed physically by an ugly complex of medical office buildings and challenged symbolically by a competing, sleek new Civil War museum at the Tredegar Iron Works, the former cannon manufactory. The Museum of the Confederacy has

fallen on hard times and into local disfavor, dismissed by some as an antiquarian dinosaur, by others as an embarrassing reminder of the racial politics of the Lost Cause. Its very name angers some who insist that perpetuating these places of Confederate history is tantamount to a modern-day endorsement of secession, slavery, and racism. According to numerous newspaper stories, the Museum and the White House are barely hanging on, and have considered closing, or dividing the priceless collection among several institutions. Their failure would be a loss to American history. Unless a benefactor comes forward to save them, their long-term future remains uncertain.

T

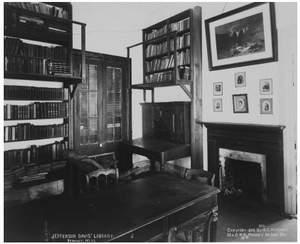

here was one place where the legacy of Jefferson Davis was safe, at his beloved postwar sanctuary, Beauvoir. There, on the Mississippi Gulf, he had found the peace that had eluded him during his presidency and during his unsettled postwar wanderings. In an outbuilding, a three-room cottage he set up as his study, he shelved hundreds of books and piled more on tables. A photograph preserves the interior of this time capsule: books everywhere, his desk and chair where he sat and composed his letters and articles, and where he wrote

The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government.

After Davis’s death, Beauvoir lived on as a monument, and it became a retirement home for aged Confederate veterans who came to live there. When the last of them died off, Beauvoir became a Davis museum and library. The institution flourished for decades until one day in late August 2005, when Hurricane Katrina hit the Mississippi Gulf hard. The main house, a lovely, nine-room Gothic cottage set upon pillars, was gutted down to the walls. All seven of the outbuildings were destroyed. Countless artifacts were lost, including Davis’s Mexican War saddle, as well as the notorious raglan and shawl he wore on the morning he was captured.

DAVIS’S PRIVATE LIBRARY AT BEAUVOIR, PHOTOGRAPHED AFTER HIS DEATH.

His library did not escape the hurricane. On that day, the sanctuary where Jefferson Davis labored to preserve for all time the memory of the Confederacy, its honored dead, and the Lost Cause was, by wind and water, all swept away.

A NOTE ON SOURCES

T

he Lincoln literature is vast. The bibliography of the Civil War is bigger. Thus, the bibliography that follows is selective, not comprehensive. It represents little more than the several hundred books on my own library shelves that I used while researching and writing

Bloody Crimes.

The cornerstone of any project touching upon Jefferson Davis must be the scholarly and brilliant multivolume set,

The Papers of Jefferson Davis,

edited by Lynda Lasswell Crist. Anyone interested in the life of the Confederate president must begin here, and no book can be written without it. At the time

Bloody Crimes

went to press, volume twelve of the

Papers

covered Davis through December 1870. Future volumes will cover Davis’s works through his death in December 1889. Also essential, because the

Papers

refer to it, because it covers Davis’s entire life, and because many books cite it, is Dunbar Rowland’s ten-volume work published in 1923,

Jefferson Davis, Constitutionalist.

Rowland’s work is crammed with invaluable information, including letters to and from Davis.

The best modern biography is William J. Copper Jr.’s

Jefferson Davis, American.

Cooper rescued the Davis story from myth and neglect and is the superior work on its subject. Anyone looking to read just one book about Davis should read Cooper. A valuable companion is his short book

Jefferson Davis: The Essential Writings.

The granddaddy of vintage biographies is Hudson Strode’s

Jefferson Davis,

published in three volumes:

American Patriot 1808-1861, Confederate President,

and

Tragic Hero.

While impaired by certain errors, and marked by an anti-Reconstruction point of view, Strode contains valuable material, influenced Davis studies and a number of books, and must be contended with.

Worthy books on the Davis shelf include Felicity Allen,

Jefferson Davis: Unconquerable Heart;

Michael B. Ballard,

A Long Shadow: Jefferson Davis and the Final Days of the Confederacy;

Joan E. Cashin,

First Lady of the Confederacy: Varina Davis’s Civil War

(though marked by a postmodern point of view suggesting that Varina suffered from a kind of “false consciousness”); Donald E. Collins,

The Death and Resurrection of Jefferson Davis;

William C. Davis,

Jefferson Davis: The Man and His Hour;

A. J. Hanna,

Flight into Oblivion;

Hermann Hattaway and Richard E. Beringer,

Jefferson Davis, Confederate President;

Robert McElroy,

Jefferson Davis: The Real and the Unreal;

Eron Rowland,

Varina Howell, Wife of Jefferson Davis;

and Robert Penn Warren,

Jefferson Davis Gets His Citizenship Back.

Difficult to read but impossible to ignore are Jefferson Davis’s memoirs,

The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government,

and Varina’s more pleasing

Jefferson Davis

…A

Memoir, by His Wife.

The ultimate Lincoln book is Michael Burlingame’s recent, all-comprehensive, and magisterial two-volume biography,

Abraham Lincoln: A Life.

No future book on the Civil War president can be written without it, and from no other work can a general reader learn

so much about Abraham Lincoln. The other vital book of the modern era is Doris Kearns Goodwin’s

Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln.

The essential library on the assassination, death, and funeral of Abraham Lincoln includes Ralph Borreson,

When Lincoln Died;

William T. Coggeshall,

The Journeys of Abraham Lincoln…From Washington to Springfield;

Dorothy Meserve Kunhardt and Philip B. Kunhardt Jr.,

Twenty Days;

Lloyd Lewis,

Myths After Lincoln;

B. F. Morris,

Memorial Record of the Nation’s Tribute to Abraham Lincoln;

Carl Sandburg,

Abraham Lincoln: The War Years;

Victor Searcher,

The Farewell to Lincoln;

Edward Steers Jr.,

Blood on the Moon: The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln

and

The Lincoln Assassination Encyclopedia;

James L. Swanson,

Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer;

Scott D. Trostel,

The Lincoln Funeral Train;

and Thomas Reed Turner,

Beware the People Weeping: Public Opinion and the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

Abott, A. Abott,

The Assassination and Death of Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States of America, at Washington, on the 14th of April, 1865

(New York: American News Company, 1865).

Abraham Lincoln:

An Exhibition at the Library of Congress in Honor of the 150th Anniversary of His Birth

(Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1959).

Allardine, Bruce S.,

More Generals in Gray: A Companion Volume to “Generals in Gray.”

(Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1995).

Allen, Felicity,

Jefferson Davis: Unconquerable Heart

(Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999).

Arnold, Isaac N.,

Sketch of the Life of Abraham Lincoln

(New York: John B. Bachelder, 1869).

Baker, Jean H.,

Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography

(New York: W. W. Norton, 1987).

Ballard, Michael B.,

A Long Shadow: Jefferson Davis and the Final Days of the Confederacy

(Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1986).

Bancroft, A. C.,

The Life and Death of Jefferson Davis, Ex-President of the Southern Confederacy: Together with Comments of the Press and Funeral Sermons

(New York: J.S. Ogilvie, 1889).

Bartlett, John Russell,

The Literature of the Rebellion: A Catalogue of Books and Pamphlets Relating to the Civil War in the United States

(Boston: Draper and Halliday, 1866).

Basler, Roy P.,

The Lincoln Legend: A Study in Changing Conceptions

(Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1935).

______, ed.,

The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln,

8 vols., plus index and supplements (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953).

Bates, David Homer,

Lincoln in the Telegraph Office

(New York: Century Co., 1907).

Bates, Finis L.,

Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth

(Memphis, TN: Finis L. Bates, 1907).

Beale, Howard K., ed.,

The Diary of Edward Bates, 1859-1866,

vol. 4 of the

Annual Report of the American Historical Association

(Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1933).

______.

Diary of Gideon Welles,

3 vols. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1960).

Bell, John,

Confederate Sea Seadog: John Taylor Wood in Exile

(Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2002).

Benham, William Burton,

Life of Osborn H. Oldroyd: Founder and Collector of Lincoln Mementos

(Washington, D.C.: privately printed, 1927).

Berkin, Carol,

Civil War Wives: The Lives & Times of Angelina Grimké Weld, Virginia Howell Davis & Julia Dent Grant

(New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009).

Bernstein, Iver,

The New York City Draft Riots

(New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

Bingham, John Armor,

Trial of the Conspirators for the Assassination of President Lincoln, s.c. Argument of John A. Bingham, Special Judge Advocate

(Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1865).

Bishop, Jim,

The Day Lincoln Was Shot

(New York: Harper & Brothers, 1955).

Blackett, R. J. M.,

Thomas Morris Chester, Black Civil War Correspondent: His Dispatches from Virginia

(Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989).

Blair, William,

Cities of the Dead: Contesting the Memory of the Civil War in the South 1865-1914

(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004).

Blake, Mortimer,

Human Depravity John Wilkes Booth: A Sermon Occasioned by the Assassination of President Lincoln, and Delivered in the Winslow Congregational Church, Taunton, Massachusetts on Sunday Evening, April 23, 1865, by the Pastor.

(Champlain: privately printed at the Moorsfield Press, 1925).

Bleser, Carol K. and Lesley J. Gordon, eds.,

Intimate Strategies of the Civil War: Military Commanders and Their Wives

(New York: Oxford University Press, 2001).

______, eds., “The Marriage of Varina Howell and Jefferson Davis: A Portrait of the President and the First Lady of the Confederacy,”

Intimate Strategies of the Civil War: Military Commanders and Their Wives

(New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 3-31.